In my opinion, one of the most impressive survival skills one can possess is knowledge of wild edible plants. I know I know, a picture of a leaf or bark on Instagram isn’t going to garner as many likes as a shiny new knife, a “one, reload, one” drill, or an elaborate flat lay of gear. However, a person with solid knowledge of plants will certainly fare better in a wilderness survival scenario than the person with the latest and greatest piece of kit.

Edible plant knowledge improves survivability, but with so many different plants, the possibility of misidentification, and the apparent reluctancy of experts to share the knowledge (it only seems this way on the surface), how do you go about learning what you can eat, what you must avoid, what can be used as medicine, and what can be processed into resources?

I won’t recommend one route over another, but I can share some insight into the correct methodology and let you decide. With summer upon us and everything in full bloom, there’s no better time to get started.

RELATED – Sleep or Die: Survival Shows Don’t Stress the Importance of Getting Rest

The Methodology

As previously mentioned, there is no secrecy to plant knowledge. You must invest your time and energy into learning it and it can’t be acquired as easily as buying new gear. The key to learning plant knowledge is relying on appropriate resources.

I learned about wild and edible plants from my late mentor, Marty Simon, who was an authority on the subject. He could ramble for hours (and he usually did) while on plant walks. I learned directly from him as so many other students did, took notes, and applied his teachings in my travels. Learning from another person is my preference, as it is the most interactive.

A good instructor will interject humor, can point to particular features, provide anecdotes, and let the students go hands-on. They will also be open to questions, follow-ups, and running themes like focusing on tubers and bulbs or succulents. They will push you to learn what you set for your objective and they will know when to broaden their presentation and when to narrow their focus. Seek out plant authorities and vet them within their community.

Even if you find THE authority on plants, never rely on single-source intelligence. Experts, as much as we want to give them credit, still get things wrong once in a while.

RELATED – Clint Emerson Teaches Readers to Live ‘the Rugged Life’ with New Book

Published Resources to Utilize

You may not have the means to attend a local course or travel to learn from a plant authority. This does not mean you have to continue living in a world where everything just looks green. I’m frequently asked, “Are there any good books about plants?” I always reply, “Absolutely.”

Long before I learned from my mentor, I had a small collection of edible and medicinal plant books on my shelf. Just by paying attention, I could link common plants to the information in the books and get a decent understanding on my own. Plants like cattail, pine, and blackberries are all easily identified even to the layperson. Other plants and “weeds” like dandelion and clover are included in this general category and are known to anyone struggling to maintain a “weed” free front yard.

You’ll learn what most people consider weeds are actually great resources with many uses. Your books should include one reference with penned lined drawings, one with a photo, and one with a color illustration. This will give you different ways to identify the plant with key features depicted/drawn.

As a good practice, always verify what you find and what you plan to do with the plant in at least three books. Using three books also gives you different perspectives if there is a chance for a poisonous look-alike.

Books are low-tech, they work when batteries fail, and they serve as silent references when no one else is around. You can use your books in one of two ways to increase your knowledge. You can walk to a wooded lot, find an unknown plant, and use your book to identify it or you can read through your books, travel to a particular environment, and look for plants that may be there based on your books. Both ways are fun and they require different sets of skills that complement one another.

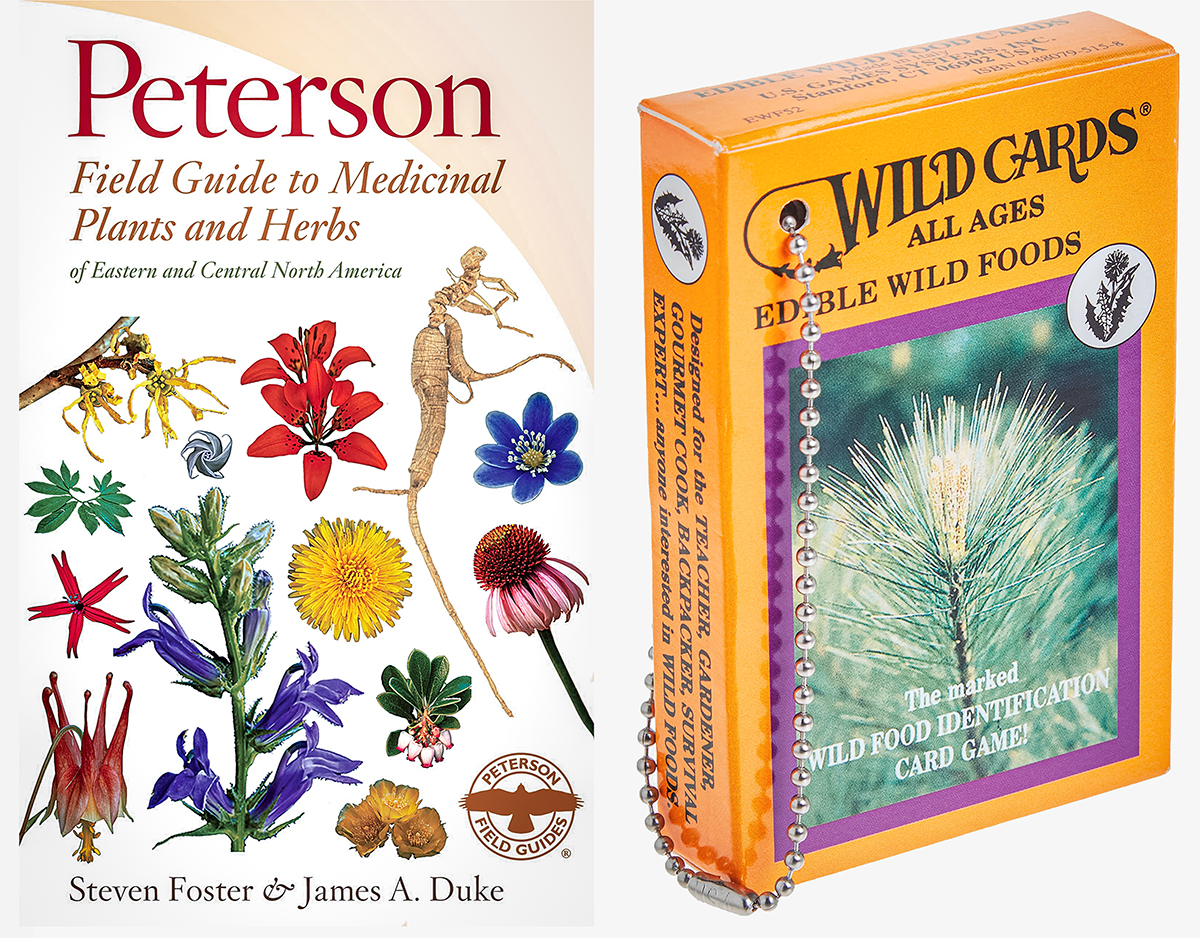

There are two old standbys that never leave my foraging pack: I like Peterson Field Guide to Medicinal Plants and Herbs and the Peterson Guide to Edible Wild Plants as well as a deck of Wild Cards: Edible Wild Foods by Linda Runyon. The edible plants playing cards are fun to pack even on longer hikes when ounces feel like pounds. They give me something to read when I’m rained in or when I find something that looks somewhat familiar but I need a supplement.

The third book I recommend varies if I’m plant identifying or plant processing. Catch me around the campfire and I’ll talk your ear off about good books. For now, visit a good bookstore, your local library, or a field office for your state’s department of environmental protection.

RELATED – Raise Them Right: Emergency Preparedness for Kids

Sites and Apps for Identifying Medicinal and Edible Plants

As much as I like being traditional and somewhat low-tech, I can’t deny the value of websites and apps in learning plants. You can find a lot of good information online but like anything on the internet, trust but verify. Keep in mind, that not all websites are created the same, and .orgs or .edus are going to likely have better content than .coms. That said, you may stumble across a dot-com website that is run by a plant authority who is the sole proprietor of a school and therefore a commercial operation.

You can join edible/medicinal plant groups on social media sites and pose questions to members. While not the same as a sage by your side in the field, a person on the other end of the computer can provide you with instant responses to your queries and they can customize their responses with photos, references to your area, and nuances books can’t cue in on.

Perhaps the most impressive app you can download on your phone is SEEK from iNaturalist. As long as you have service, you can use SEEK to scan plants, insects, or animals and it will tell you the scientific name of what you are viewing. You can use your phone to deeper dive into an understanding of the plant.

Set Goals

Taking an in-person plant walk, relying on books, and using online sources will help level you up. The temptation will be to learn as much as possible as quickly as possible but this leads to developing an understanding of plants that is a mile wide and an inch deep. But be aware of potentially reaching your saturation point. You can only retain so much information in a single day without practicing it over time.

I would suggest a more governed approach starting with 10-12 plants, then working up to a goal of 24, then 50, 100, and so on. Learn to identify plants in every stage of their development. Learn it by sight, smell, and touch. You can even mark them with surveyor flags during one season so you can come back and find them when they are not as obvious.

A good goal to set is identifying plants that are survival food, great for cordage, and good for making topical salves from the category approach. Eventually, you’ll find yourself in the great outdoors seeing the environment with a different set of eyes that see plants for what they offer instead of how they look.

Keep in mind, that plant knowledge is perishable. Unlike the cool gear, you buy that will likely outlive you, you can lose plant knowledge like any other skill set if you don’t practice it and no plant “expert” will say their study is complete. Learning plants is a lifelong pursuit which is why so many won’t invest the time in it as the reward takes time to earn. That said, each time you positively identify a plant, it’s a reward you can experience over and over. Or, you could just buy another piece of gear to sit next to the rest of your stuff.

This content was originally posted by Fieldcraft Survival in April 2022.

READ NEXT – The Fallacy of the ‘If You Had Only One Survival Tool’ Debate

Comments