A shocking burst of full-auto gangland payback in 1929 that left seven bloody, bullet-ridden bodies on a garage floor was the Parkland Shooting of its day. The now infamous St. Valentine’s Day Massacre was a horrendous display of violence that the general public was not accustomed to, even at the height of Prohibition and the crime wave that came with it.

The story went viral, covered by practically every newspaper in the country. It even went out on the wireless, which is what many people were still calling radio at the time.

There’s an old saying in the newspaper industry: If it bleeds, it leads. Well, there was more than enough blood shed on Feb. 14 in Chicago that year to ink sensational headlines on front pages from California to Maine. And back then, people had time to dwell on bad news for way longer than 24 hours.

The widespread reporting of the bloody massacre led to a significant attitude shift among many Americans. In a country that had held the Second Amendment as sacrosanct, there were now everyday people saying there’s no reason regular folks should be able to own a machine gun like those Chicago Typewriters used on that dark Valentine’s Day almost a century ago.

It got a ball rolling that led to the passage of the first piece of major federal gun control legislation in U.S. history just five years later that’s still on the books today, though there have been additions since. Here’s how it all went down.

GOOD GEAR – Surprise Your Loved One With a BRCC Valentine’s Day Gift

How and Why the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre Happened

It was the height of Prohibition, and Chicago was a nexus of illegal hooch — and in Chicago, Al Capone’s South Side Gang was king.

The OG Scarface had had a decade to solidify his organization’s position in the Chi-town underworld and in the black market network of illegal alcohol, but that doesn’t mean there weren’t competitors who wanted their crack at the throne, including George “Bugs” Moran’s crew known as the North Side Gang.

When Moran started making moves against the South Side’s alcohol business, Capone decided it was time to take drastic action — allegedly.

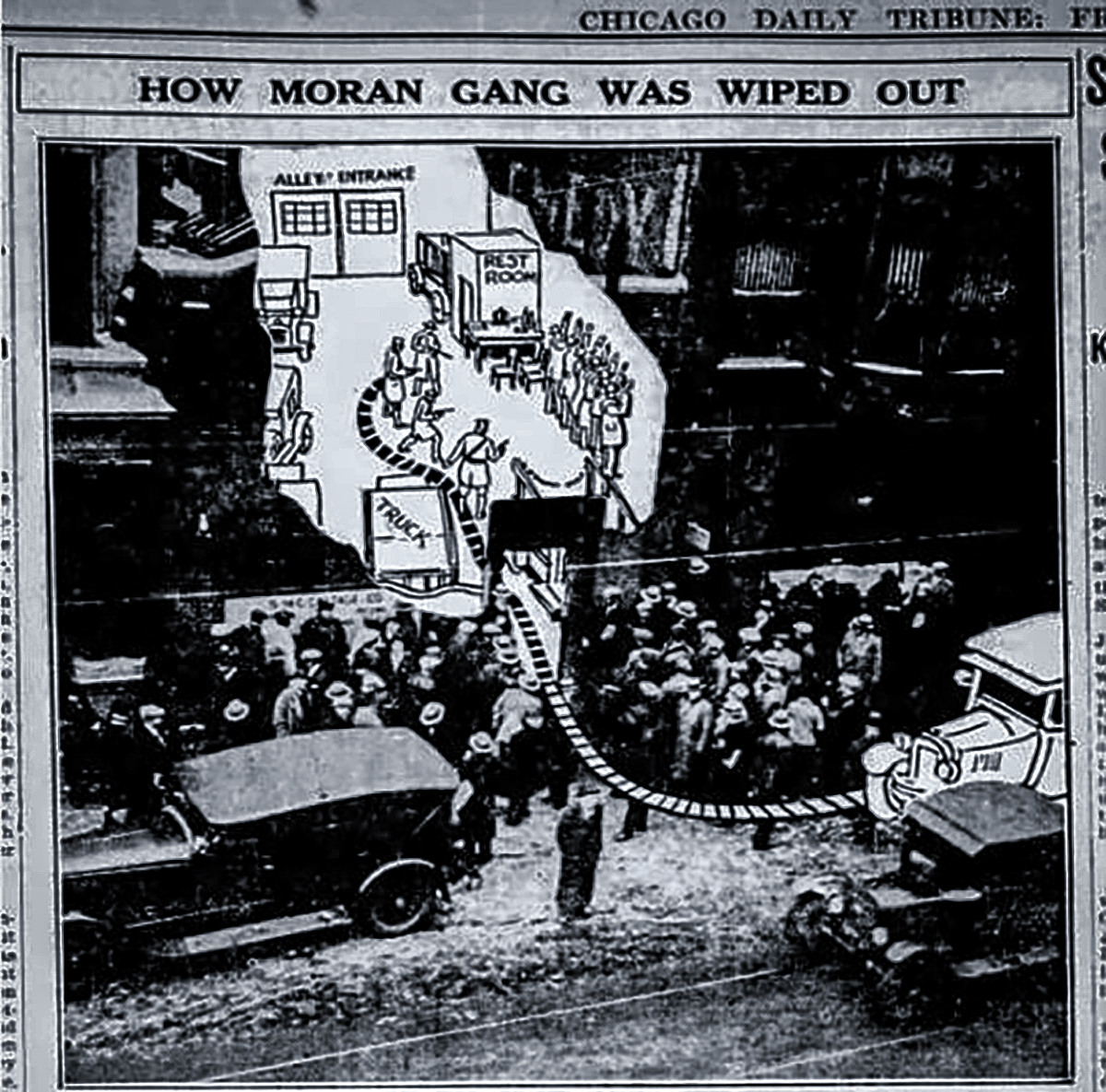

On Feb. 14, 1929, the kingpin sent four men, who were never conclusively identified, to the S.M.C. Cartage Company garage at 2122 North Clark Street, where Moran’s gang regularly hung out. The seven men they found inside were lined up against a wall at gunpoint — and all seven of Moran’s men were cut down in a hail of Thompson submachine gun fire — 70 rounds in all.

The victims were Peter Gusenberg, Frank Gusenberg, Adam Heyer, John May, Al Weinshank, Reinhardt H. Schwimmer, and James Clark — all but Gusenberg died at the scene.

When the real police showed up, they found him still clinging to life with 14 bullets in him. They asked him who shot him, and in typical underworld fashion, he said, “No one shot me.” Gusenberg died in the hospital a few hours later.

But there was more to it. The massacre was actually a failed hit on Moran himself, who should have been in that garage for a meet, and almost was.

Moran had been encroaching on Capone’s territory bit by bit and had recently hijacked a shipment of whisky from Canada that belonged to the South Siders. Capone wanted to take him out for good, though he was at his home in Florida at the time and was in no way connected whatsoever at all.

The original plan was to set up Moran and some of his lieutenants by getting them to meet at the garage on N. Clark Street on Valentine’s Day with a cut-rate deal on good whisky. The deal was set up by Detroit’s Purple Gang so as not to raise suspicion, but that crew was in Capone’s pocket. Because of this supposed meeting, the massacre victims were all dressed in their best duds.

Things were going as planned. Moran’s guys showed up at about 10:30 a.m., but there was no Moran. He was running late, and when he and one of his men approached the rear of the garage, they saw a police car, ducked into a coffee shop, and chilled there. The theory goes that Capone’s men saw Weinshank, who was roughly the same height and build as Moran, thought it was him, and said, “It’s go time.”

The witnesses who actually talked to police said they saw a Cadillac pull up in front of the building, and four men got out, two of whom were dressed like police officers. They all entered the garage together.

They found Schwimmer and May first. The two fake cops lined everyone in the garage up against the wall as if they were going to be arrested and then gave a signal to their two plainclothes partners, who opened up with their Tommy guns. One used a 20-round stick magazine, and the other was running a 50-round drum mag.

Once they’d burned through all 70 rounds, they blasted May and Clark’s faces with a shotgun for good measure. The only survivor, ultimately, was the garage dog.

To cover for all the gunfire with lookie-loos in the street, when the four men exited the building, the two dressed as police pretended to be taking the two machine-gunners into custody.

The story had it all, and it was all over national front pages. The juxtaposition of such a ghastly murder on what is supposed to be a romantic holiday, the fact that the killers dressed as cops and were still at large, and the overkill statement of using machine guns all combined to capture the nation’s imagination.

To top it off, there were 16 gang-style killings in Chicago that year, racking up 64 fatalities.

Politicians, otherwise helpless to stop the spread of gang violence, found a scapegoat in the modern, high-powered firearms of the day, and pop culture decided it was standard issue for every gangster and their brother to get a Tommy gun along with a fedora and a top coat.

RELATED – Assault Weapon Ban of 2023: Biden Fully Supports Proposed Law

The Era of Gun Control Begins

The headline-grabbing gangland shooting applied a dark undertone to a sappy greeting-card holiday and got politicians and newspaper editorial boards talking about gun control in earnest. In the years between 1929 and 1934, the push for gun restrictions commenced — first at the state level, then at the federal. Sound familiar?

In a letter from the editors published in the Waco-News Tribune in 1933, the paper wrote: “Why should desperadoes, brazen outlaws of the period, be permitted to purchase these weapons of destruction?” in reference to machine guns after Texas banned them.

President-elect Herbert Hoover planned to use the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre as a springboard for a gun control policy, but the crash of the stock market and the Great Depression kinda got folks distracted for a few years. But crime waves continued, and brazen, violent outlaws like the Dillinger gang, Machine Gun Kelly, Baby Face Nelson, and Bonnie and Clyde kept grabbing headlines.

At the time, federal law didn’t treat machine guns any differently from other firearms. They could be sold to anyone, despite some state and local regulations, without any special permits or licenses, and they did not have to be registered. If you’ve ever seen the Kevin Costner flick The Highwaymen, that’s pretty much how it was. You could just walk into a gun shop and pick a Thompson SMG or a Browning BAR off the wall, assuming they had one in stock and you could afford it.

But while crimes involving machine guns got a lot of press, statistically, there weren’t many of them. That’s because machine guns weren’t all that common or available. Why? Most people didn’t have a practical use for them.

In 1929, a Thompson would set you back about $200. That’s about $3,500 in today’s dollars — not exactly the kind of heater every mob thug would have in a case under their bed. The criminals who actually used weapons like the Thompson and BAR typically stole them from police stations, gun stores, and sometimes National Guard armories, and they were often passed around or re-sold in underworld circles.

As the 1930s, Prohibition, and the Depression wore on, President Franklin D. Roosevelt introduced his sweeping New Deal plan to get the country and its people back on its feet. While the program created jobs and huge construction projects, it also included “A New Deal for Crime,” which included the National Firearms Act of 1934 (NFA). It passed and went into effect on June 26, not long after Bonnie and Clyde’s crime spree ended in a hail of gunfire, some of it full-auto, on May 23, 1934.

Despite the perceived crime wave, gun control was not a popular concept at the time, and the government knew it couldn’t outright ban machine guns, so instead, the NFA and its taxing system were created to make it prohibitively expensive for the majority of people to buy machine guns legally.

The price of the tax stamp at the time would have doubled or tripled the cost of such a machine gun or other prohibited firearms seen as “crime” guns of the day, like short-barreled or sawed-off shotguns, pistols with stocks, and suppressed firearms. Plus, the guns had to be registered with the feds to be legal.

The arguments against the NFA were much the same as the arguments against “assault weapon” bans today. Check out this bit from a 1934 Chicago Tribune editorial:

“It is notorious that when restrictions are put upon the possession of firearms or any particular kind of weapon they never are effective against the criminal classes but only put the peaceable man at a disadvantage or in a false position before the law. The prohibition does not bother the enemy of society but it makes a technical offender of the decent citizen. The man who would not misuse a weapon is the man who is injured. The drive for public security is thus given the wrong direction.”

Soon after the NFA went into effect, gangland violence seemed to decrease — at least, it wasn’t grabbing headlines the way it used to. Know what else happened not long before the NFA went into effect? Prohibition ended, all but destroying the lucrative black market for alcohol overnight. On Dec. 5, 1933, the 21st Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified, which repealed the 18th Amendment and Prohibition.

Legal booze was flowing again, and organized crime turned its attention back to mainstays such as prostitution, gambling, racketeering, and the growing narcotics trade. Soon, the country would have World War II occupying its headlines.

GOOD GEAR – Spartan Kick Your Tastebuds With the BRCC Ready To Drink 300, Vanilla Bomb

The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre Guns, the Birth of Forensic Ballistics, and the Infamous Wall

While nobody was ever arrested for perpetrating the crime, the machine guns used in the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre were eventually recovered by authorities.

The investigation went nowhere until a break came on Dec. 14, 1929, in St. Joseph, Michigan. Earlier that night, one of the suspects in the shooting, Fred “The Killer” Burke, was driving drunk, got into a fender bender, and attempted to flee. Police chased him, and Patrolman Charles Skelly bravely jumped onto the running board of Burke’s car. Burke shot Skelly three times, killing him on the spot.

Police later found the car abandoned and traced it to a Frederick Dane, which they realized was one of Burke’s aliases. When they raided his place, they found a whole bunch of wild shit.

The dude had two Thompsons with nine 50-round drums — one gun was assembled, loaded, and ready to go, while the other was broken down in a black suitcase. They also found five 100-round drum magazines, three 20-round mags, two rifles — a Winchester .351 semi-auto and a Savage .303 — a sawed-off shotgun, two bags of ammo estimated to hold 5,000 rounds, and six tear gas bombs.

Police also found a trunk containing a bulletproof vest and about $320,000 in bonds that had been recently stolen in Wisconsin.

The machine guns were turned over to the Chicago police, who used the new technique of forensic ballistics in a privately funded lab to match the guns to the bullets recovered at the crime scene. Through this method, they also found that one gun had been used to kill New York mobster Frankie Yale. But that was all they could dig up. The forensic science success, however, led to the creation of the Chicago Police Department Crime Lab.

As for Burke, he was captured on a farm in Missouri more than a year later. There was a rock-solid case against him for the murder of Officer Skelly. He was tried for the crime in Michigan, convicted, and sentenced to life, but he was never tried in connection to the massacre. He died in prison in 1940.

The two Thompsons, serial numbers 2347 and 7580, are still around. Gun 2347 had originally been purchased by Deputy Sheriff Les Farmer in Marion, Illinois, in 1924. Farmer had ties with a gang in St. Louis, and the gun was in Burke’s possession by 1927.

Gun 7580 was sold at a Chicago sporting goods store to a man named Victor Thompson, but it wound up with James Shupe, a small-time hoodlum with ties to Capone’s gang.

Today, the guns are still in the custody of the Sheriff’s Department in Berrien County, Michigan.

THE WALL

The garage where the massacre took place immediately became a tourist attraction and remained so until it was demolished in 1967. But it gets a lot weirder after that. A Canadian businessman, George Patey, reportedly paid a few grand for 414 bricks from the rear wall where the seven men had been lined up and shot. He shipped them to Vancouver, where he took them on the road to show them at galleries and shopping malls as a morbid curiosity — like a sideshow.

Most venues weren’t interested. After a few failed ventures, Patey assembled the bricks into a wall and set them up in a 1920s-themed nightclub in Vancouver — in the club’s men’s room — covered by Plexiglass. Patrons could actually aim their piss at targets on the glass against the wall.

Somehow, the club went under after a few years. Patey sold some of the bricks as souvenirs and eventually unloaded the rest for $200,000 in 1996.

Most of the bricks were eventually acquired by the Mob Museum in Las Vegas, where they were reassembled into a wall yet again, and supposed bullet holes were emphasized with red paint. You can still see it there today.

READ NEXT – Fight Is on To Kill the ATF’s Impending Pistol Brace Ban

Comments