Here’s a corner of American literature they won’t teach you about in class. Or maybe they do. What do I know? It’s a cool story, and if you have a cool teacher or professor, they could totally waste half a class with this one.

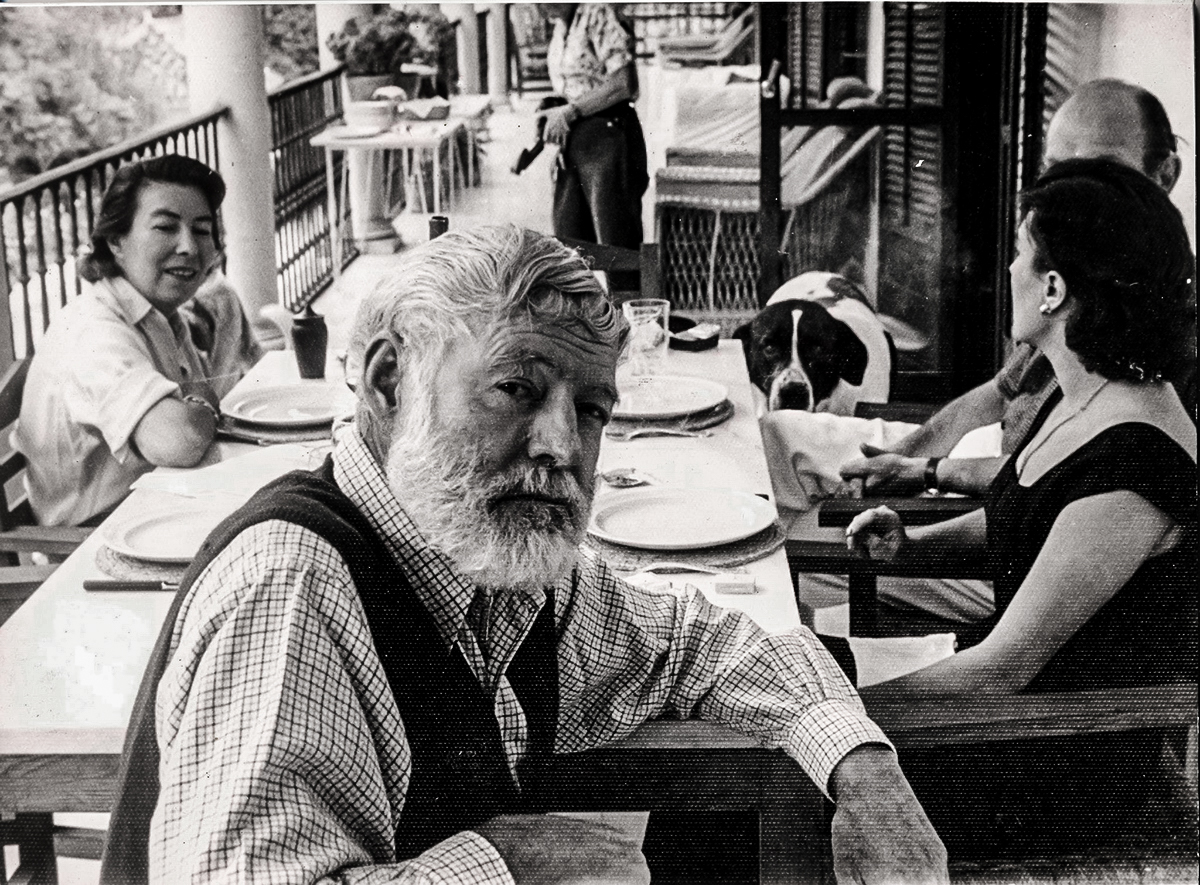

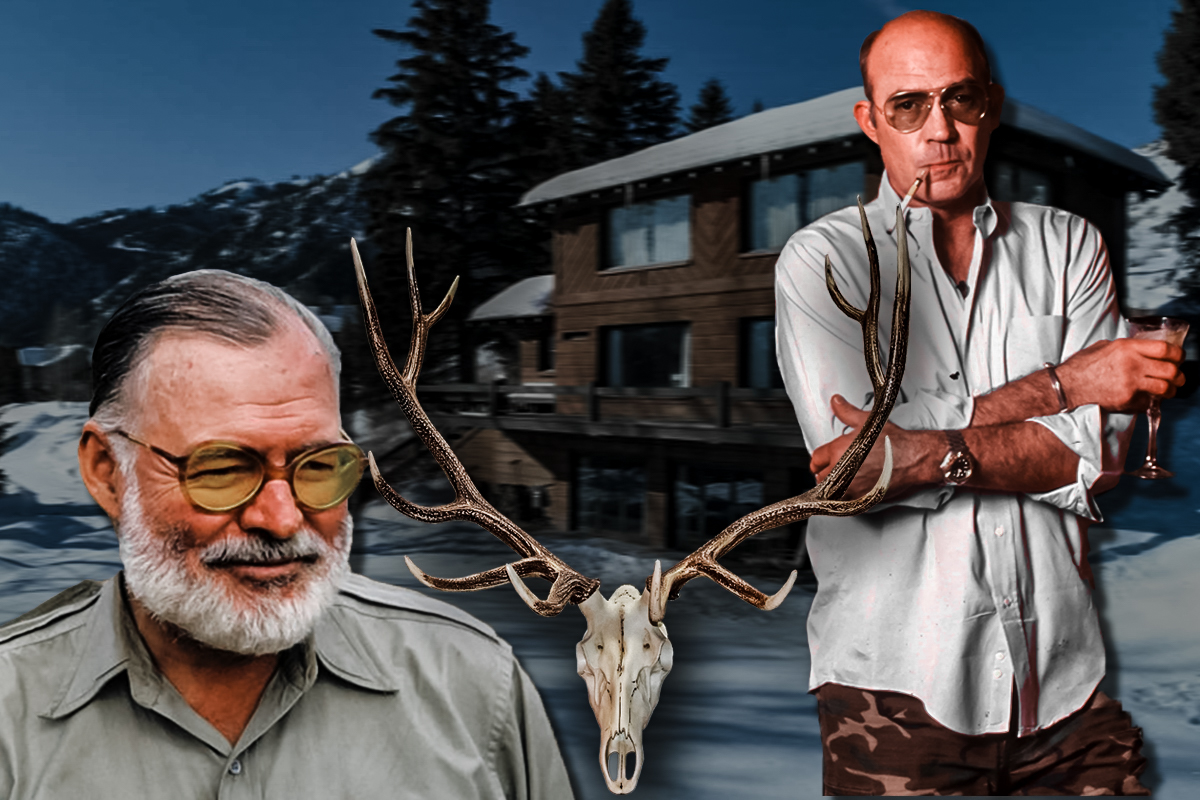

Two legendary rock stars of the printed word — Ernest Hemingway, the renaissance man, war correspondent, and imposing father figure of American prose, and Hunter S. Thompson, the endlessly weird, always heavily armed, and unrivaled father of gonzo journalism — once crossed paths. Sort of, indirectly, via elk antler theft while on assignment for a national magazine.

Hemingway died in 1961 when Thompson was ramping up his professional career. The latter had just returned to the U.S. mainland after a year in Puerto Rico (where he gathered the experiences that eventually influenced The Rum Diary), so it’s unlikely the two could have ever physically crossed paths.

Before that, Thompson was a copy boy at Time magazine — briefly — until he was fired for assaulting an office candy machine and pissing off an advertiser. It’s not likely he and Papa Hemingway were swimming in the same circles.

No, this connection came much later and is more of a Thompson kinda story than a Hemingway tale.

In 1964, a lot happened in Thompson’s life. His new wife, Sandra Dawn Conklin, gave birth to their son, Juan; the family moved to California after a brief stint in Aspen, and Thompson started using Dexedrine as writing fuel, which would be replaced by cocaine in later years.

He also took an assignment for the National Observer that sent him to Hemingay’s former home in Ketchum, Idaho, to write a piece about the author’s suicide and why Hemingway came back to the town after living as an expat in countries all over the world for most of his life.

While at Hemingway’s now mostly empty home in Ketchum, Thompson, who was 27 at the time, impulsively grabbed a set of 6×6 elk antlers — presumably one of Papa’s hunting trophies — that were hanging over the front door of the cabin where Hemingway had taken his own life only a few years earlier. Then he shoved them in his car and took off.

Thompson kept those antlers for decades at his rural home in Woody Creek, Colorado, his famous haven just outside Aspen.

While Thompson may have hung on to the thieved trophy that once belonged to a writer he deeply admired, it apparently never sat easily with him. He didn’t show the antlers to any of his many visitors at Owl Farm over the years, nor did he tell the story behind them. In fact, Sporting Classics Daily reports Hunter left them hanging in his garage for years.

His wife at the time of his death, Anita Thompson, said in an interview with BroBible.com back in 2016 that Thompson “got caught up in the moment. He had so much respect for Hemingway. He was actually very embarrassed by it.”

When Thompson — in failing health — took his own life in 2005, he did it much the way Hemingway did: with one of his own shotguns at his home in Woody Creek, where the antlers still hung in the garage.

In 2016, 52 years after Thompson snatched a souvenir from his literary idol – a man whose novel (A Farewell to Arms) Thompson once retyped entirely to better learn the author’s style — Anita drove those elk antlers back to Ketchum in her Prius and returned them to the place they rightfully belonged.

Those antlers may have been on Thompson’s mind, along with Hemingway himself, in his final days when he decided his ride was over. Before he took his own life, SCD reports that he nailed a missive to his front door reading, “Please don’t steal from this home, by the management.”

The story Thompson wrote for the National Observer was reprinted in a collection of his works, The Great Shark Hunt: Strange Tales From a Strange Time:

“He knew something had gone wrong with both himself and his writing, and after a few days in Ketchum you get a feeling that he came here for exactly that reason. Because it was here, in the years just before and after World War II, that he came to hunt and ski and raise hell in the local pubs with Gary Cooper and Robert Taylor and all other celebrities who came to Sun Valley when it still loomed large on cafe society’s map of diversions.

“Those were ‘the good years,’ and Hemingway never got over the fact that they couldn’t last. He was here with his third wife in 1947, but then he settled in Cuba and 12 years went by before he came again — a different man this time, with yet another wife, Mary, and a different view of the world he had once been able ‘to see clear and as a whole.’

“Ketchum was perhaps the only place in his world that had not changed radically since the good years. Europe had been completely transformed, Africa was in the process of drastic upheaval, and finally even Cuba blew up around him like a volcano. Castro’s educators taught the people that ‘Mr. Way’ had been exploiting them, and he was in no mood in his old age to live with any more hostility than necessary.

“Only Ketchum seemed unchanged, and it was here that he decided to dig in. But there were changes here too; Sun Valley was no longer a glittering, celebrity-filled winter retreat for the rich and famous, but just another good ski resort in a tough league. ‘People were used to him here,’ says Chuck Atkinson, owner of the Ketchum Motel. ‘They didn’t bother him and he was grateful for it. His favorite time was in the fall. We would go down to Shoshone for the pheasant shooting, or over river for some ducks. He was a fine shot, even toward the end, when he was sick.’”

Today marks Hemingway’s 124th birthday, and Thompson would have been 86 this year — two writers who changed the tone of American literature and are forever inextricably linked by suicide and one set of stolen and returned 6×6 elk horns.

Hopefully, they’re all in some version of Hunter’s Owl Farm or in a Caribbean bar on a different plane, with Thompson holding court, waving around a glass of Chivas, as Hemingway pours his perfect martinis for F. Scott Fitzgerald, and now, another for the late Cormac McCarthy.

This content was originally posted in July, 2023.

READ NEXT – Cormac McCarthy, Creator of the Anti-western Novel, Dies at 89

Comments