Bowhunting for reindeer takes a good amount of skill and stealth in the 2020s. Ancient hunters 1,700 years ago in what is present-day Norway had to have Marine Scout Sniper-level skills. Now, there is well-preserved physical evidence of exactly how they got within 20 yards of spooky reindeer in open, rocky ground.

At 6,300 feet above sea level, the mountainous Norwegian landscape is stark. Receding ice sheets have left horizons of glacial rubble. Snowfields blanket sporadic, patches many acres in size. There are no trees. No natural cover. It was much the same centuries ago. Hunting grounds were only as good as you made them.

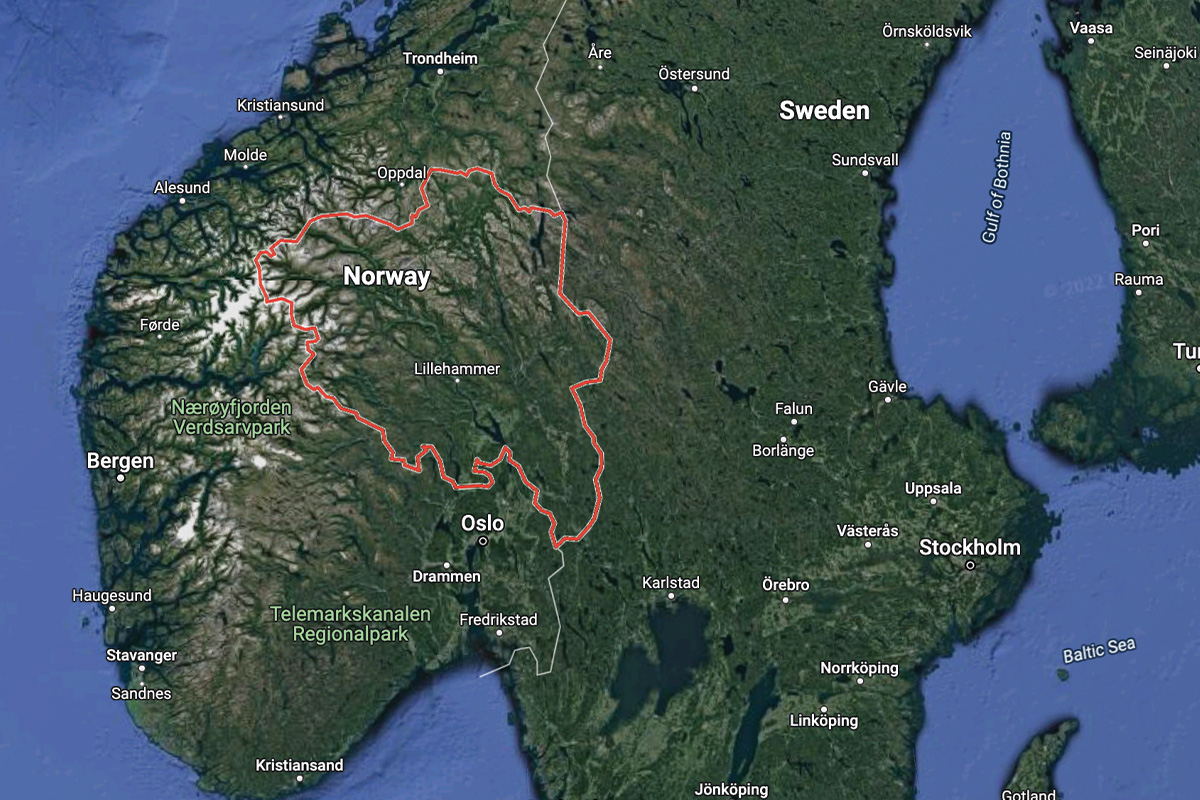

In one such place, a peak known as Sandgrovskaret in the county of Innlandet, Norway, a team of archaeologists from Secrets of the Ice uncovered a trove of artifacts left behind by ancient hunters that offer a glimpse into how archers brought down reindeer in a much more primitive age.

The team first discovered a few hunting artifacts back in 2013, but returned for a more thorough expedition in 2018. Those findings are now being released.

Among the discoveries is a rare type of Iron Age arrowhead only seen in this region once before in a grave that dated to some time between the years 550 and 600.

While the rare arrowhead is a unique discovery, the larger story of the strategy and tactics hunters used to kill their ungulate prey in this wide-open landscape is told by other artifacts in this archeological treasure trove.

Forty hunting blinds were mapped at Sandgrovskardet, and the team found 32 “scaring sticks,” 5 arrows, and 77 pieces of reindeer antler and bone.

RELATED – WATCH: Hunter-Gatherers and the Meaning of Life

The hunting blinds were built from stones and gave hunters natural-looking cover on the open rocky landscape. The direction the blinds face also shows the hunters who made them had an understanding of where the reindeer were going to move through.

Of course, herd movement is unpredictable and there were pretty strict limitations on a bowhunter’s range at the time. Hunters had to get animals within about 20 yards of their blind to make an effective shot. The “scaring sticks” helped make that possible.

The sticks were usually about three feet tall, with something like a thin birchbark flag attached at the top that would flap in the wind.

According to Espen Finstad, one of the archaeologists on the team, these sticks were stuck into the ground like fence posts and were used to “scare” the animals into position.

“You would bring a bunch of these sticks to the mountains,” Finstad explained. “And depending on weather and wind and where the reindeer are found, you would calculate how best to make them move toward the hunting blinds and place lines of these sticks along the ice.”

The movement from the sticks would alarm the reindeer and cause them to move in the opposite direction.

Scaring sticks are the most common finds from the melting ice in Innlandet. Some sites have hundreds, others just a few; more than 1,000 have been recovered in all.

Finds like these from ancient hunter-gatherer communities are helping European archaeologists piece together a better picture of life during the Stone, Bronze, Iron, and Viking Ages, as well as the post-Viking medieval period.

Rare discoveries in North America are doing the same.

Recently, a National Park Service employee found a wooden hunting bow preserved in Lake Clark National Park and Preserve in southwest Alaska. Researchers say the bow is up to 500 years old.

Because the bow most closely resembles a Yup’ik or Alutiiq style bow, which is normally found in Western Alaska or the Alaskan Peninsula, its location in Lake Clark suggests the possibility of interaction with the Dena’ina people who lived in the region.

Jason Rogers, an archaeologist for Lake Clark National Park and Preserve, said the bow was a “very rare” find since land developments in Alaska, which often uncover archaeological artifacts, are not as common as in some other parts of the world.

READ NEXT – Ishi, Pope, and Young: The History of Modern Bowhunting

Comments