In today’s world, it’s easy to take the lever-action mechanism for granted. It may be more than 160 years old, but it’s still going strong, thanks to companies like Winchester, Henry, and Marlin, and the shooters who love the guns produced under those big names. With a modern perspective and having seen how popular and useful lever guns became in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the platform’s success might seem to be a foregone conclusion. In reality, lever actions had a rather rocky start when they were first introduced as the lesser-known Volcanic pistol.

Awkward design, failed business ventures, and underpowered ammunition plagued the concept, though at its core it was a good design perfected by the two guys who would go on to create Smith & Wesson, though they couldn’t get it off the ground either. Eventually, it would become the standard for repeating rifles for a long time to come.

With the help of some of the brightest minds of the time, the Volcanic pistol’s failure became a phoenix rising from the ashes. The lever action became the most iconic firearm mechanism of the 19th century, soldiering through the 20th and into the 21st. And thanks to its inclusion in a popular Old West video game (although it is wildly overpowered), its progenitor, the Volcanic pistol, and its unique history are being rediscovered by a new generation.

GOOD GEAR – Survive the Day With BRCC’s Endurance Roast

A Rocky Start for the Volcanic Pistol

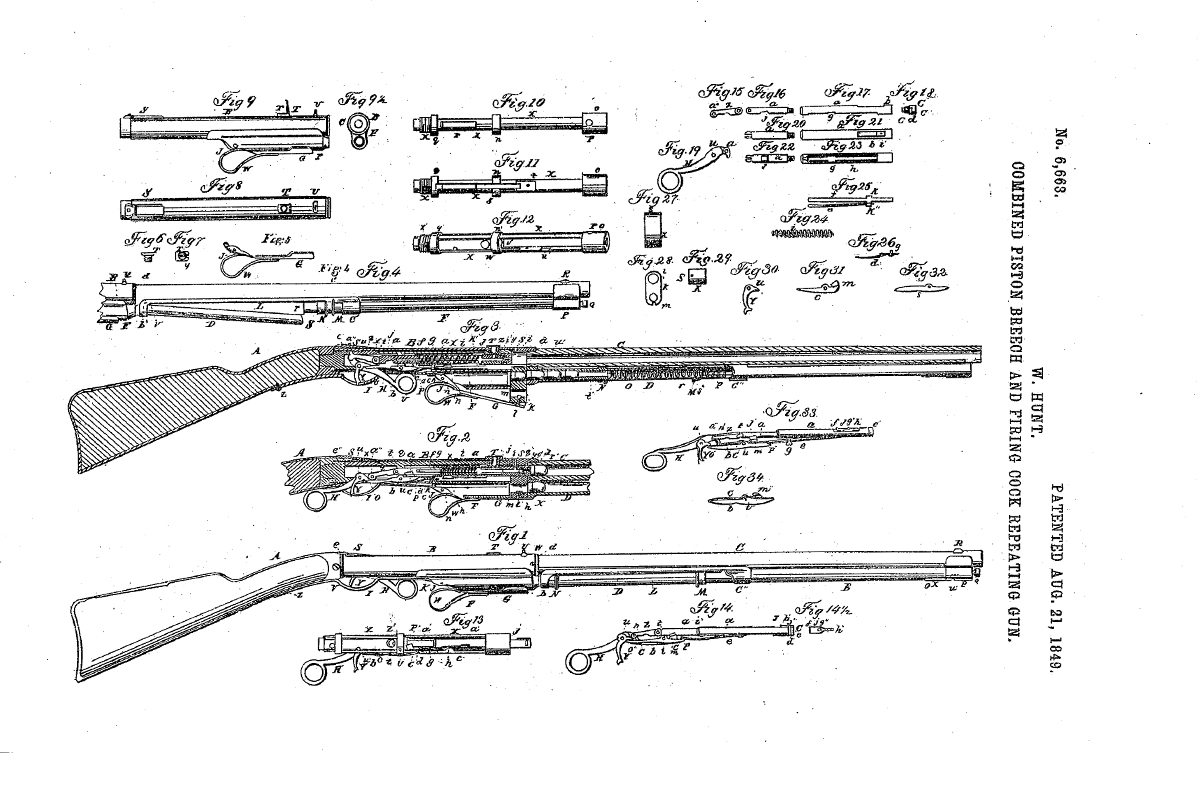

The Volcanic pistol’s genesis came in 1848, when New York inventor Walter Hunt patented a new kind of ammunition that did away with paper cartridges — no, not the metallic cartridge, that would come later. In 1849, he patented a repeating rifle to fire his new caseless ammo — more on that in a bit.

The actual lever action worked, in principle, much like those we are familiar with — a lever was manually manipulated to cycle the action with chambered ammunition from a tubular magazine that ran beneath the barrel. It worked, just not very well.

Hunt was an inventor, not a manufacturer. He licensed the rifle’s design to Lewis Jennings, a gunsmith in George Arrowsmith’s New York City gun shop.

In short order, Jennings and Arrowsmith realized that Hunt’s design was dead in the water. Instead of trying to reinvent (or, in this case, invent) the wheel, Jennings set to work on improving the rifle’s mechanism, which was originally designed by Hunt. Thankfully, Jennings was able to develop some workable improvements, patented them, and assigned the patent for the Jennings rifle to Arrowsmith.

With the kinks worked out of the design (or, at least, so they thought), investor Courtland Palmer joined the team to breathe financial life into the project. Palmer contracted with Robbins & Lawrence to produce 5,000 of these new repeating rifles, known as the Jennings Repeating Rifle.

When the Winchester Repeating Arms Company was still in its infancy, in 1871, Oliver Winchester himself recognized the historic importance of the Jennings, as he referred to the rifle, as the “connecting link in the history of our gun [the Winchester lever action].”

Sadly, the design wasn’t improved enough because the guns still didn’t work well. Many were converted to single-shot so they could be fired at all.

In 1850, Palmer tasked Horace Smith (yes, the Smith of later Smith & Wesson fame) with making even more improvements to the repeating rifle. Smith delivered, and a 5,000-gun production run was completed in 1851. At that point, Palmer pulled the plug on the project.

In 1852, Smith moved to Worcester, Massachusetts, to work for the Allen, Brown & Luther tool company. During this time, he met Daniel Baird Wesson, who was also tinkering with the idea of repeating firearms. They didn’t know it at the time, but it would be the most critical meeting of both men’s lives.

Horace Smith and Daniel Wesson formed the first and lesser known of their two eventual partnerships that same year. For the next two years, the duo concentrated almost solely on developing a repeating pistol.

Once completed and brought to fruition, these Volcanic pistols were among the first functional repeaters. They utilized a new lever-action mechanism. They also fired an improved version of a primitive — yet revolutionary — type of self-contained ammunition.

READ NEXT – 8 Gauge Shotgun: Why It Went Extinct

Caseless Ammunition and the Volcanic Lever Action Pistol

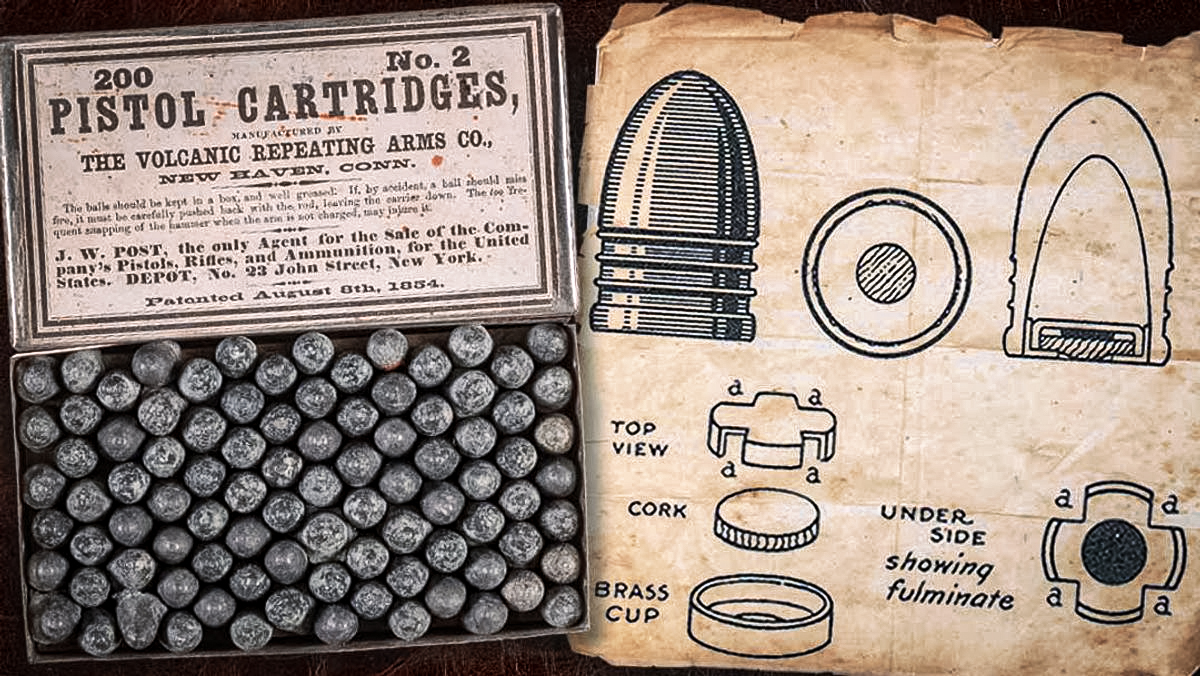

Inventor Walter Hunt patented his Rocket Ball ammunition in 1848. Hunt’s new design sought to eliminate traditional paper cartridges, considered state-of-the-art for more than a century. Hunt’s creation was a new caseless type of ammunition. The self-contained metallic cartridge that is ubiquitous today was still some years away from development.

Hunt’s .31- and .41-caliber bullets had hollow bases packed with a charge of gunpowder.

The powder-filled cavity was then closed with a waterproof cap. The cap had a small hole through which the ignition source, an external primer, could travel and reach the powder.

When fired, the bullet’s hollow base expanded to engage the barrel’s rifling, which helped improve accuracy. The cap stayed behind, ending up in front of the next chambered round by operating the gun’s lever.

While Hunt’s design was a step forward, it had flaws — particularly its lack of power. The round’s powder charge was small, so it could fit within the base cavity of the pistol caliber bullet. The construction resulted in a round that lacked muzzle velocity and terminal effectiveness.

Seeking to improve upon Hunt’s design, Smith and Wesson patented a similar cartridge in 1856. It was essentially Hunt’s Rocket Ball with a primer inserted into the hole at the rear of the bullet.

Like the Rocket Ball, Smith and Wesson’s cartridge came in .31- and .41-caliber variations. Unfortunately, S&W’s improvements did little to enhance the cartridge’s muzzle velocity or effectiveness.

GOOD GEAR – Fuel Your Next PR With BRCC’s Fit Fuel Blend

Tooling Up and Making the Volcanic Work

In June 1854, Smith and Wesson partnered with Palmer, who owned the previous patents. Palmer also had the necessary $10,000 in capital to tool up for making the guns.

Together, the three men were in a powerful position. They had full patent protection on every part of the new guns and ammo they were trying to bring to market.

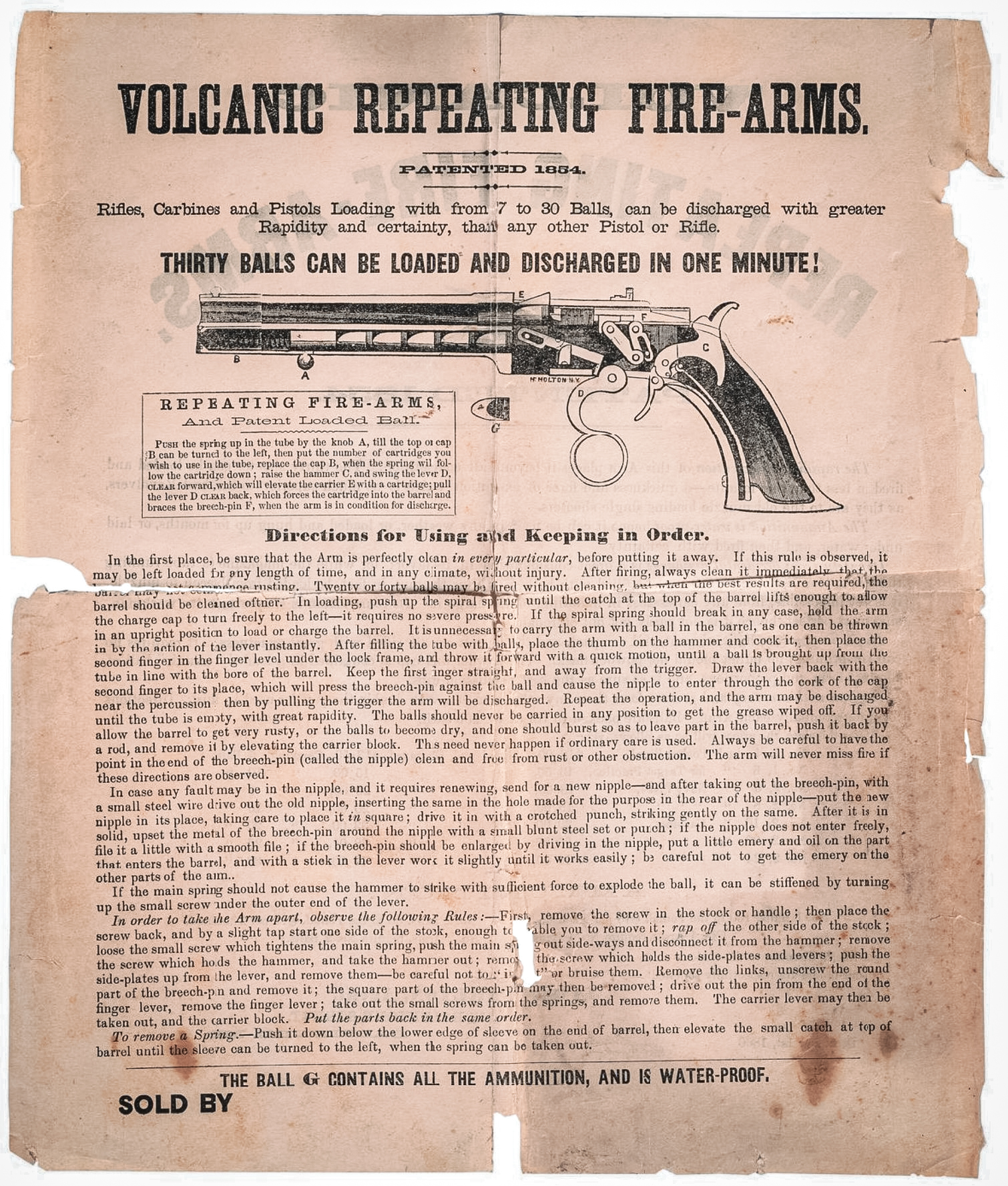

The Volcanic pistol operated similarly to the lever-action firearms still in production today.

Once the magazine was loaded, the shooter racked the finger lever forward. The motion cocked the hammer and raised a cartridge from the magazine into line with the barrel. Closing the finger lever, which also acted as the trigger guard when closed, pushed the cartridge into the barrel’s breech. From there, the shooter could pull the trigger and fire the pistol.

Working the lever allowed the shooter to fire again and again until he cycled through all the rounds. In the age before revolvers, when a multi-shot firearm meant a double-barreled shotgun or rifle, this was a big deal.

The main difference between the Volcanic pistols and later lever actions is that Volcanic pistols had no ejection port because they didn’t need one — caseless ammo has nothing to eject after firing.

READ NEXT – ATF Pistol Brace Rule in Effect June 1: What You Need To Know

A Volcanic Eruption

Exactly when and where the Volcanic name came from is lost to history. We do know that Walter Hunt named his original repeating rifle The Volition Repeater. The “Volcanic” moniker may be a bastardization of this.

Or, the name may have been inspired by Scientific American’s review of the gun, where they compared its firing to the fiery eruption of a volcano.

You can believe whichever version you prefer, but the Volcanic pistol definitely had a badass name — far more badass than this underpowered handgun actually deserved.

The Volcanic pistol was a groundbreaking design, but it was filled with faults, most of which stemmed from the caseless ammunition. When it worked, it worked flawlessly. When it failed, it failed fantastically.

If the chamber was too deep or the cartridge’s diameter too small, the cartridge would slide forward into the barrel and get stuck. It essentially created an unfired squib round in the barrel. They were just as challenging to remove then as they are today.

It was also a fairly delicate mechanism that would not have held up well to the dust and grime of the real world, not to mention the fact that caseless ammunition was extremely susceptible to moisture and damage from mishandling. It also wasn’t the most ergonomic or easy firearm to use — notice there haven’t been a lot of lever action handguns since.

GOOD GEAR – Embody the Ethos of the Quiet Professional With BRCC’s Silencer Smooth Roast

A New Direction

Like many small 19th-century arms makers, Smith and Wesson’s company soon succumbed to financial issues in late 1854. The duo’s first partnership dissolved early the following year, although it would reform in 1856.

Even though the partnership disbanded, the company itself wasn’t dissolved. Instead, it changed hands to an owner who was also interested in repeating firearms. It also changed names. The new owner was Oliver Winchester.

At the time, Winchester was a clothing manufacturer with no firearms experience. He reorganized the failed gun company and renamed it Volcanic Repeating Arms Company. It later became the New Haven Arms Company.

Volcanic guns and ammunition were unreliable, underpowered, and unpopular. However, Winchester wasn’t about to throw the baby out with the bathwater. Instead, he hired expert gunsmiths to refine the Volcanic designs. Those innovations eventually led to the creation of the Winchester Repeating Arms Company.

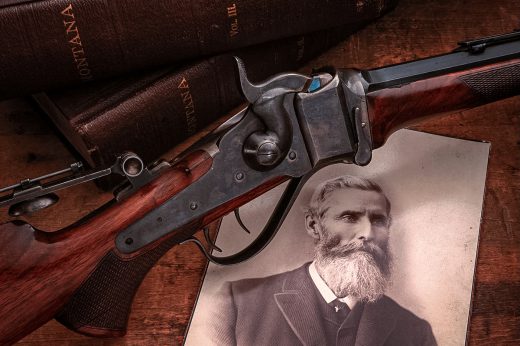

Winchester’s first success was the Model 1866 lever-action rifle. The gun was nicknamed “Yellow Boy” because of its brass frame. The gun may have been a Winchester, but the design wasn’t completely original.

It was actually an improved version of the earlier Model 1860 lever-action rifle invented by Benjamin Tyler Henry, better known as the Henry Rifle. The rifle’s loading mechanism was a holdover from the original Volcanic design. It worked far better because it was able to take advantage of newly introduced metallic cartridges instead of the finicky and underpowered caseless stuff.

But the design needed refinement for use in the field. The Henry required bringing the follower to the muzzle end and pivoting the magazine tube to the side to load an ammunition round — a cumbersome process. The design also necessitated a tab attached to the follower in the tube magazine so it could be pushed and locked to the forward position. This required a large channel to be cut the full length of the mag tube, ready and waiting to let in all kinds of grime.

And, as the shooter worked through the magazine, the tab moved toward them, requiring them to adjust their offhand position at some point — all of this also precluded the inclusion of any type of handguard on the rifle.

It may have been an enormous step forward in firearms development, but it was far from perfect. In addition to all that, the Henry design was also fragile and prone to failure. In spite of this, Winchester recognized the gun’s potential and acquired production rights. By 1866, with only 14,000 rifles manufactured, production ceased.

Winchester floated multiple new designs for an improved version before landing on the final configuration. The company reintroduced Henry’s rifle with a newly designed loading gate and a wooden handguard. It became Winchester’s first commercial success.

Winchester’s next two guns were the Model 1873 and Model 1876 lever action repeating rifles. Winchester really came into its own with these two designs, achieving impressive sales and support from several big-name shooters.

William “Buffalo Bill” Cody said the Model 1873 was “the boss.” Theodore Roosevelt declared the Model 1876 “by all odds the best weapon I ever had.”

It would likely have played out very differently if not for the humble Volcanic.

A Lasting Legacy

The public has largely forgotten the Volcanic pistol, save for some die-hard gun collectors, firearms history enthusiasts, and Red Dead Redemption gamers.

Still, the design deserves more respect and recognition than it is usually given. If not for the Volcanic, Winchester’s Model 1873 would never have become “The Gun That Won the West.”

More significantly, there would be no Winchester. Period.

There would be no Marlin lever guns, modern-day Henry rifles, or unusual lever-action AR-pattern firearms such as the wild lever gun introduced by Bond Arms at the 2023 SHOT Show.

The gun might be little more than fodder for game designers and a footnote in the history of firearms, but it’s an extremely important one that shows even small steps that result in initial failures can often contribute to massive successes, given enough innovation and refinement — and good marketing.

READ NEXT – Rifle Backpack Guide: Buy One That Doesn’t Suck

Comments