Forty-degree wind and spitting rain blow unabated from Canada’s northwestern territories, gusting to 25 miles per hour. The rain hits my jacket and the back of my hands with the sharp snap of firecrackers as I stand waist-deep in the murky water of Lake Michigan, fly rod in hand.

My buddy Cameron stalks a small cove tucked into a point with 20 or so spawning carp somersaulting around the shallow water. The fish all have a one-track mind, are love drunk, and not interested in eating. A few break off and swim into a spit of submerged rocks that extend like a pigtail from the shore near where I’m posted up.

With some makeshift Kentucky windage, I cast blindly into the murky water to intercept the break-off carp. Every time the fly grabs a rock on the bottom, adrenaline dumps into my blood. False-alarm fatigue soon settles in. My mind starts to wander. My casting goes on autopilot.

The line stops short again, and I figure it’s another big rock. Until it moves and then picks up steam. All I can do is crank down my drag, hold my rod high, and follow the fish along the ankle-busting shoreline.

Carp will bolt on you at every opportunity. Carp bolt when hooked. They often bolt again when they see an angler at the end of the line. They bolt into half-submerged shoreline brush, tall grass, and rocks — they try to, at least. They bolt when you think they’re finally out of steam. They will take line and try to bust you off right until you touch them. They bolt when you pry your fly out of their rubbery mouths.

I outlast the bolts. Finally, I get close enough to kneel and grab its soup-can-thick tail. I forget about the blowing wind, the firecracker rain, the fishless hours in a freezing boat, and the throbbing in my hands, my neck, in the back of my head.

Over the rain and wind, fish in hand, I hear Kevin, our guide, howling from shore, “Anyone who could catch a carp today is the motherfucking man!”

Beaver Island is probably the finest big carp fishery in the country, and sight-fishing for them on tropical-looking flats with a fly rod is one of the most satisfying and frustrating ways to chase these golden submarines. Beasts over 40 pounds are not uncommon here, cruising the flats and mudding into the soft bottom for crayfish, gobies, small crustaceans, and worms. They’ll grab insects off the surface as well, sucking them down like a kid hiding from mom with a bag of Halloween candy.

Still widely regarded as an invasive trash fish by the conventional tackle world, carp are sometimes called “golden bones” by fly anglers: a blue-collar version of the bonefish found on actual tropical flats. Like true bonefish, they have earned respect as a very picky, very wary species that is a riot to fight on light tackle. But unlike actual bonefish, carp are ugly-beautiful. They’re rough, rubber-lipped, muscle-stuffed, copper-and-gold swimming pigs.

Big carp are the annual summer siren song that calls Cameron and me, along with buddies Alex and Mike, to fish this remote archipelago in northern Lake Michigan. Our guide-friends Kevin and Steve help us answer that call every year.

I first met Kevin, Alex, and Steve on a bourbon-fueled, extremity-freezing, almost fishless late-November steelhead trip in Michigan nearly a decade ago. I’ve called Cameron and Mike friends for almost that long as well. It’s the combination of our shared history and fishing jones with the vibe of the island that makes this an annual trip none of us would think of missing, short of our own deaths. Or COVID.

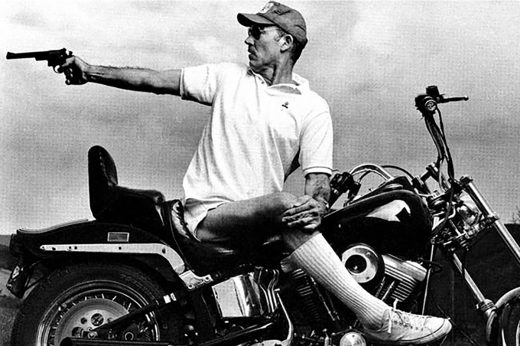

Kevin does not look like the typical, fueled-by-Simms-Copenhagen-and-Mountain-Dew kind of guide. He’s in his early 50s, clean-cut, and professional to the point of near formality, but he’ll tell you if your cast sucks. Until you’ve spent enough time deciphering his subtle social cues and dry humor, it’s tough to figure out if he actually likes you or if he’s simply tolerating you.

Alex is a charismatic, exceedingly well-read, mustached professional photographer from Phoenix. He’s also a gun and food aficionado and can recite the entire dialogue of Full Metal Jacket, word for word, with mind-blowing accuracy — and he does the voices, too.

Every time I fish with these two, their conversations head for deep water as soon as we settle into a long, quiet patrol. They cover philosophy, astrology, and anthropology. They talk about obscure books by obscure thinkers, religion, the impossibility of true love, and the technologically-saturated state of humankind. All the while, I’m on the lookout for fish while listening to a series of live, original TED Talks.

In contrast with Kevin, Steve is pure chew-and-Dew and built like a grizzly with paws to match. His hats are threadbare and sweat-stained, there’s always a tear in at least one article of clothing he’s wearing, he ties deadly carp and smallmouth flies, and he’s as laid-back as Kevin is professional. Two completely different dudes, both super fishy.

Mike is a writer, photographer (for love, not money), guitarist, and rabid soccer fan from North Carolina who will travel to fish at the drop of a hat. He also consumes books like perfectly cooked brisket — with both hands until he’s full or asleep. Thanks to a year of quarantining, he looked like Nostradamus, or maybe Moses, with a fly rod on this trip.

Cameron is the host of our trip. His family is from Northern Michigan, so he’s known about Beaver for a long time. He works in law enforcement in South Carolina, has a borderline unhealthy thing for fiberglass fly rods, and has organized this annual fly fishing pilgrimage to Beaver for 11 years. He’s the friend that checks in out of the blue right when you need someone to check-in.

The four of us missed our 2020 pilgrimage due to COVID. Between travel restrictions, the fact that fishing from boats was off-limits, and our go-to bars and restaurants were all closed. The trip had to wait — which blew for Kevin and Steve, who earn 1/3 of their annual income on the island. COVID fucked 2020 good, but we were back for 2021.

We plan our annual seven-day trip to Beaver knowing that we’re bound to get at least one weather day — when the wind has northern Lake Michigan wound up and frothing, the boats stay on their trailers, and morning coffee is enjoyed slowly with a breakfast wrap in rocking chairs on the porch. It’s usually a welcome break after a couple of hard days of fishing.

But when the weather day happens on day one of fishing, an early, subtle jab of panic throws the rest of the week into doubt, especially if the forecast for the upcoming days is a mixed bag. We’re all here to fish ourselves nearly to death, and none of us like being told we can’t do so right out of the gate.

Even with the early weather day, we’re determined to unfuck the rest of the week and make up for the loss of 2020. The next morning brings marginally better conditions and a slightly improved forecast. Even so, it’s not the start we were hoping for.

Kevin stands behind Alex and me, hand on the tiller, slowly idling his 18-foot Polar Kraft through a skinny break in a football-field-sized shoal. He then cuts the motor and climbs onto his platform to navigate us back into a bay by push-pole.

Shoals and reefs are everywhere throughout the Beaver Island archipelago. They guard all 11 islands, so we never take a straight line from one spot to the next.

We could be balls-out running across open, clear-as-glass water, and 50 feet of depth can suddenly vanish. Submerged plateaus and ridges of off-white sand and rocks suddenly appear within 2 feet of your prop, even closer in some spots.

This morning is overcast, cold, and misting rain. It’s the kind of rain that soaks you slowly, and you don’t realize it until the cold leeches into your backbone by way of a leak at your collar.

Not the kind of rain you want while not seeing fish. At least the wind isn’t blowing like yesterday, and tomorrow is supposed to be in the high 70s. Summer has lost its ever-loving mind.

The three of us can’t keep count of how many brutal fishing days we should’ve abandoned over the years but instead suffered through and stuck it out. Addiction is a lousy teacher.

Today, however, after almost three completely carpless hours, none of us is willing to die on that cross. We’re heading into known pike water and change our terminal tackle accordingly: bigger flies and wire bite tippet.

“Today’s a good day for pike,” Kevin says.

I know he means the conditions are right, but I think to myself, today would be a good day for a fucking sunfish.

“Make a long cast there,” he points. “Count the fly down to 10. Strip slowly to start, then speed up.”

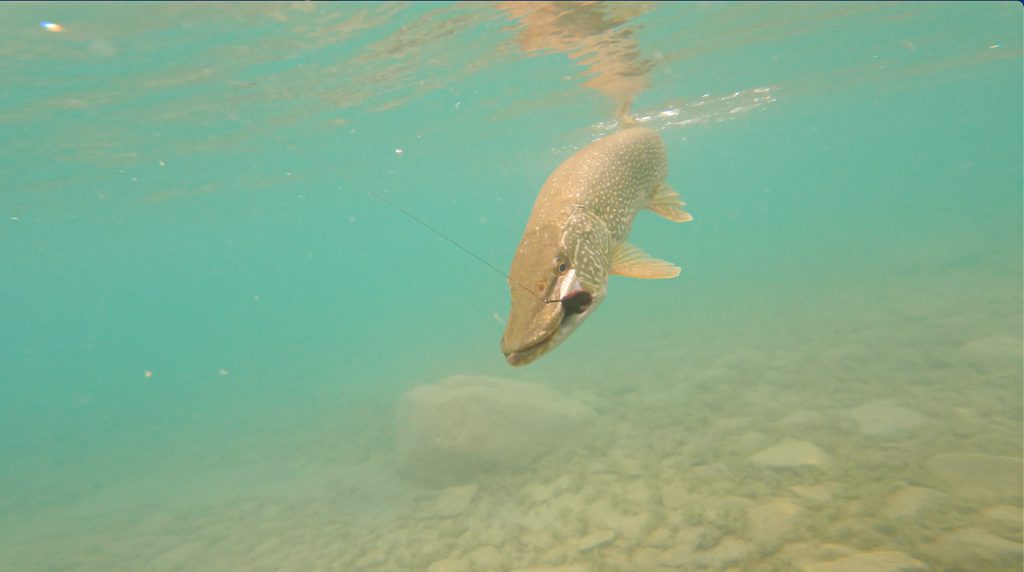

My third strip stops short with a heavy grab. The pike turns into a good hookset as he points his wide head toward the bottom and bolts.

Pike use every inch of their length as leverage as they make slashing, full-body turns and shake their head with jaws clamped tight. The rod bends in cursive swings, not the morse code punctuation of a smallmouth fight. There’s less urgency and more annoyed anger.

The fight isn’t long, but it’s exactly what I need. With the first fish in the net, a feeling of relief fills the boat.

Unlike any other fish, pike look at you when you’re holding them. Their predator mind is still at work, almost patiently studying its surroundings. There’s no panic. They simply don’t acknowledge that anything could be higher on the food chain.

Alex and I trade catches like this a few times, reminding our muscles what a good-fighting fish feels like and driving the cold out of our swollen, bloodied fingers. Pike have more teeth than you’ll ever be able to avoid.

The action cools off after the fifth fish. Kevin poles the boat back toward a section of tall grass in shallow water, and we turn our attention to smallmouth.

The Beaver Island archipelago is situated in northern Lake Michigan, less than 20 miles from the shores of the Upper Peninsula. The main island is a 15-minute charter flight from Charlevoix or a 2-hour ferry ride from Traverse City. The 37,000-acre chunk of limestone bedrock and glacial till has roughly 550 year-round residents and hosts thousands of summer tourists.

There are three uninhabited barrier islands that stand sentinel just north of Beaver, three smaller islands just west of them, one even smaller outlier further northeast, and a final tiny mound that’s due east and barely registers on GPS.

They have names like Garden, Hog, Hat, Shoe, Bird, Squaw, Trout, and High. Some are home to thousands of wild, scrub pine and thorn brush-choked acres; some are barely a spit of white sand and rocks held down by mouthy gulls, cormorants, and an occasional eagle. Every one of them is draped in mosquitoes and deer flies. Every one of them holds fish.

Beaver Island proper was originally home to a population of Chippewa and a small number of white families before James Strang, who proclaimed himself king of the Mormons after Joseph Smith was assassinated, arrived with his disciples in 1847.

Strang set aside most of the island as property of the church and turned it into a busy port for steamers on Lake Michigan. He even served as a member of the US House of Representatives. Then he took five wives, which pissed off Native Americans, white settlers, his fellow politicians, and Mormons who didn’t agree with Latter-day Saint doctrine on polygamy. At the time, only 20% to 30% of LDS families actually practiced polygamy. By 1856, his disciples and the other island residents turned on him, and like Smith before him, he was assassinated.

As carp guides, Kevin and Steve complement the unique feel and slightly quirky history of the place just right.

Over their decade and a half of summer-long residency, the two men have become as much a part of the island’s fabric as chicken and waffles at the Dalwhinnie Deli, walleye sandwiches at the Shamrock Pub, or boxing your own groceries at McDonough’s Market.

Day three starts in near silence, except for a few gulls sitting on boats in their slips and the soft ting of the cook scrambling eggs with a spatula in Dalwhinnie’s kitchen. We slip onto the lake, unable to tell if we’re actually moving because the surface is so still and the sky so clear.

The afternoon is all blue sky and 70-degrees. Steve spots a pair of big, bright carp from his poling platform slowly cruising 80 feet from the boat and talks Alex into their location. Alex makes sure his fly line is clear of snags at his feet and pinches his leader between his fingers, letting the fly dangle gently below his hand.

Alex has the hot hand every year when it comes to carp. I’m certain that his mustache carries moxie that somehow translates to the fly, rendering it irresistible to the barbeled torpedoes, but I can’t prove it.

Steve positions the boat, so Alex has a clear backcast, and Alex lays out a cast that falls just short.

“Fifteen more feet,” Steve whispers.

Alex picks up his line and makes another cast with the added distance. Both carp turn and start closing on the fly.

“Keep moving it,” Steve guides. “Strip, strip, strip. Stop.”

For one pregnant moment all three of us hold our breath, waiting to see which carp would inhale first. Beating both of them to the punch, a 6-pound smallmouth bass appears from the ether, splits the carp, and steals the fly.

“No!!” Alex roars. “Fucking smallmouth! Goddamn it!”

Only here could a trophy-size smallmouth be a despised bycatch.

An angry southeast wind cuts our fourth day in half, so Cameron and I walk Gulf Harbor Drive, a dirt road along the northeastern side of the island, to check out a wading spot where we caught a dozen carp in flooded tall grass a couple of years back. The road winds through pines until it disappears into the persistent chop of waves rolling up to the shore. The worn lines of submerged tire tracks hint at where the road used to continue around Sucker Point.

Even with lake levels dropping a little this year, Lake Michigan has risen almost 7 feet since 2014, the first year I came to Beaver. On my last trip in 2019, water had laid claim to hundreds of acres of shoreline woods and pushed bays back into previously dry inland areas. Carp were spawning back in spots so thick with brush that their coital wrestling matches sounded like a moose thrashing its way out to charge us.

Given the slightly lower lake level, our spot is calf-deep and silty and holds zero carp. This section is semi-protected by the flooded road, so the only water deep enough to hold fish is directly inside the built-up stone.

I make a short cast and a bowfin, with its neon-green fins and dragon-like dorsal fin, grabs my fly. My next three casts produce small smallmouth: 8- to 12-inch fighters that think they’re twice that size.

Cameron wades over and we fish a few yards apart, catching these little brawlers on almost every cast. We’re running late for dinner, but neither of us is ready to reel up and wade out.

“Just think how big these guys will be next year,” he says.

“Hopefully, they don’t turn into assholes like their parents,” I reply.

We’ve had thin years in the past, for sure. We’ve failed. But this year almost feels like a personal attack.

Later at dinner, Kevin has two words for the lack of fish in all the expected places and their spookier-than-normal behavior: sparkle boats.

Glitter-wrapped bass boats that don’t think twice about running skinny over the shoals at 40 mph or if they prop-scar a flat getting to another location after they’ve beaten an entire bay into a coma.

I know a lot of bass fishermen: some professional, many just lifelong die-hards. I grew up chasing largemouth. But something wacky slipped into the gene pool with these dudes. Fuck.

They’re after smallmouth. The freaks that average between 4 and 5 pounds in this remote location. Pike is the less popular but still pestered bycatch. Sparkle boats are putting the wood to more fish, more often, in more locations than Beaver has seen, maybe ever. The shift in fish behavior — carp included — is not surprising.

We’re lucky to have had this place pretty much to ourselves for so many years. But there’s an unspoken sense of disappointment that everyone carries because we all know how good it can be.

Stories pour out around the table as quickly as the waitress brings fresh drinks.

We recount days that we could do no wrong when 20- and 30-pound carp would eat our flies whether they were circling in a daisy chain like tarpon, mudding on the bottom, suspended in 11 feet of water, sunning inches from your feet in tall shoreline grass, or rolling around in a spawning herd of 20. They’d eat and run with the downhill power of linebackers.

Smallmouth would fuck up anything that hit the water. Big bass — some pushing 7 pounds — covering 25 feet in a heartbeat and T-boning a goby imitation.

Pike, especially the ones over 40 inches, grabbing a streamer, severing the leader, and sulking off before I could even flinch.

All this Nat Geo-level shit played out in absolutely clear-as-your-8K-flatscreen water.

It’s good to soak in days like those. Store them in your memory like really good whiskey to open and share with friends on days where all any of you have is an empty flask.

Or fucking sparkle boats.

Read Next: Record Grass Carp Caught By Angler Fishing for Smallmouth

Comments