A few weeks ago, my landlord came knocking at my door on a Tuesday morning. When I answered, he said, “I’ve got a dead beaver out here. You want it?”

What are you supposed to say to that?

“Sure, I’ll take it!”

The words fell out of my mouth well before I realized I didn’t have any idea what the hell to do with a dead 37-pound beaver or how to process it even if I did. But I knew I wanted to make like a guy from the 18th century and take a shot at tanning the animal’s tail with nothing but a throwback attitude and the breadth of collective internet knowledge.

It soon became apparent that I did not have the skills to tan an entire beaver pelt, but the tail — I thought I could manage to tan the tail. Maybe. Sort of. And while figuring it out, I would get a glimpse into the rich history of trapping and part of how they processed the beavers they took, first hand.

Smell the Butt, Eat the Beaver Tails

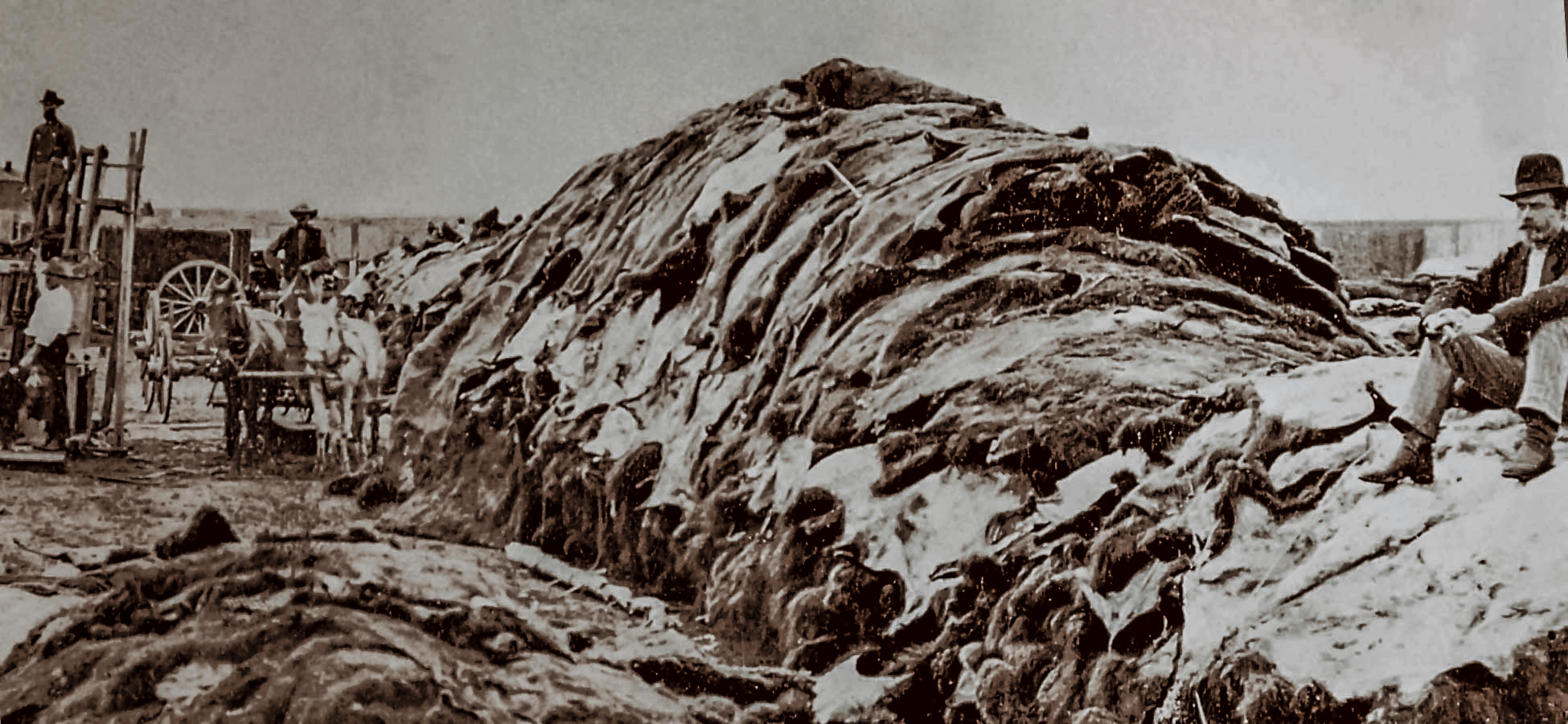

The beaver-trapping business is an old one; its zenith came in the 18th and 19th centuries, mainly due to the fashion industry in the US and especially overseas. Beaver fur was all the rage, and the fur’s excellent ability to repel water made it an especially sought-after material for hats and other garments.

But what about the tail? After processing, beaver tails were extremely useful for making a number of high-quality leather goods. Plenty of folks have also been known to eat beaver tail — no not the Canadian treat made of deep-fried dough topped with cinnamon sugar and whipped cream with the same name — folks do eat actual beaver tails, especially trappers.

There are a number of ways to prepare what was once thought of as a mountain man’s delicacy. There’s no real amount of meat to be had from the tail, but it’s where a beaver stores most of its body fat.

When you skin a beaver, you’re not going to find a lot of subcutaneous fat like you would on a raccoon, because it’s all in the tail. If you were living in the backcountry for months on end, trapping and purely living off the land, that readily available source of good, pure fat would have been most welcome and perhaps necessary for survival and maintaining reasonable health. In a modern context, you can cook the tail, remove the fat, render it, and have a supply of high-quality cooking fat that can be used for all sorts of things.

In the old days, you’d encase the tail in clay and cook it on some hot coals, and then cut through the charred leather and the inner membrane to get to that pure fat. If your landlord ever drops a fresh beaver on your stoop and you’re brave enough, you can do the same by wrapping it in tin foil and throwing it on the grill.

Surprisingly, folks who have eaten that fat report that it’s basically tasteless. It can also be rendered and used like lard to cook other things.

The tails are pretty damn useful when still attached to the beaver, too. Beavers can slap that large, flat tail on the water surface to issue a danger warning, and it works extremely well as a rudder when they swim. On land, the sturdy tail, which is typically a foot long and 2 inches wide, is useful as another leg to help beavers reach branches and to stabilize their bodies when going to work on a tree trunk.

The animals also use their tail as a lever when dragging bulky and heavy branches into position for dam building. Some people think beavers also use their tails to pack mud into their dams, but they actually use their front feet.

Now, about the smell. You may have heard somewhere that beaver tails smell like vanilla. That’s sort of true. Beavers have castor sacs, a scent gland that creates a chemical compound in the form of a thick yellowish goop, called castoreum, which they use to mark their territory. The glands are actually located under the tail, so it’s the beaver’s ass that smells like vanilla, not the tail itself.

Castoreum smells and tastes so much like vanilla that it’s been used as a food flavoring and in perfumes — but these days, most vanilla scents are synthetic and castoreum is rarely used in vanilla extract (but it’s still on the FDA’s list of approved food ingredients, so you never know).

Because of their fur, skin, tails, and sweet, sweet ass-stink sacs, beavers were hunted and trapped nearly to extinction on two continents. There were only 1,300 Eurasian beavers in the wild at the beginning of the 1900s.

The North American beaver was also nearly hunted out of existence for their pelts and vanilla ass juice. There were an estimated 100 to 200 million beavers on the continent. By the early 1800s, there were hardly any.

But time marched on, and so did the fashions that required an abundance of beaver pelts. Demand declined and trappers moved on to other quarries and professions as the American Frontier dwindled.

Since then, reintroduction efforts in the US, Mexico, and Canada have been successful and their populations are once again abundant.

The Eurasian beaver population has also made a comeback, though not as dramatic, thanks to reintroduction efforts in France, Germany, Poland, and in parts of Scandinavia and Russia.

RELATED – Wildlife Scientists Lead the Charge in Montana’s Cwd ‘Zombie Deer’ Fight

Beaver Trapping in the 21st Century

Today, very few people make a living by trapping beavers. Instead, most are hobbyists and amateurs.

Beavers are amazing creatures, but they can wreak havoc on the local landscape, which is exactly what was happening on my landlord’s property. They were felling trees with tremendous speed and building dams that were causing flooding and cutting off the water supply to a large pond in a state-managed wildlife refuge that butts up against the property. That pond eventually empties into a nearly 700-mile-long river. So, with the blessing of the government officials in charge of the refuge, my landlord began setting traps and dispatching beavers. And that’s how I wound up playing 21st-century mountain man.

Tanning Beaver Tails

Before I got to tanning, I hit GoWild, a social media community geared toward the outdoors, and a bunch of users chimed in with their own experiences, best practices, and words of encouragement. I used what seemed like a couple of solid YouTube tutorials as guides, a few meager cutting implements, and just jumped into it. Fair warning: If you aren’t a patient person, you might want to tap out about now.

Lesson 1: Don’t Cut to the Tip on Beaver Tails

The first task, obviously, was to remove the tail, which was accomplished with a pocket knife and little difficulty.

Then, I cut the tail in half along the edges and began removing the outer skin. Most of this process was really easy, but as you get closer to the tip, the tail gets really thin. I made a couple of wrong moves that an experienced hand would not have made, and put some small holes in the tail leather.

I also discovered that any injury the beaver sustained to its tail that had healed over created really tough scar tissue was all but impossible to separate from the thin outer layer of the tail, resulting in a few more small tears.

Actually pulling the tail apart was more difficult. The interior fat is incredibly slimy and slippery, so I clamped the tailbone in a small bench vise and then got a good solid grip and started pulling the two halves away from the bone. The tactic worked, and they came apart relatively easily.

Later on, I learned that you don’t have to try to split the tail all the way to the tip. Just get as close as you can without feeling like you’re going to risk poking through. If you get to this point, then the tail is usually thin enough to separate itself cleanly into two pieces just by pulling it apart.

RELATED – Sporting Dog Restrictions Fail in NH, Falter in MD, Progress Elsewhere

Lesson 2: Use the Right Knife

Next, all the fat and other tissue must be removed from the soon-to-be leather. I learned quickly that having a proper fleshing knife for the task, which I did not, would have made this step a lot easier. I made due with my sharp skinning knife, but the blade’s contours weren’t right for the task and it took a lot longer than it should have, and the results weren’t as clean or thorough as they should have been.

Lesson 3: Tendons Are Tough

I also learned that all of the tendons in the tail closest to the spine are incredibly tough. Given the power that a beaver’s tail has, this makes complete sense, but those sinewy little fibers were abnormally strong and definitely gave even my sharpest knife a run for its money.

With as much of the flesh removed as possible, I was set to start the actual tanning process. It wasn’t difficult, but it was time-consuming.

RELATED – Shed Hunting Tips From Connor Clark: How to Rule the West

Salt and Wait, Acid and Wait, Base and Wait, Wash

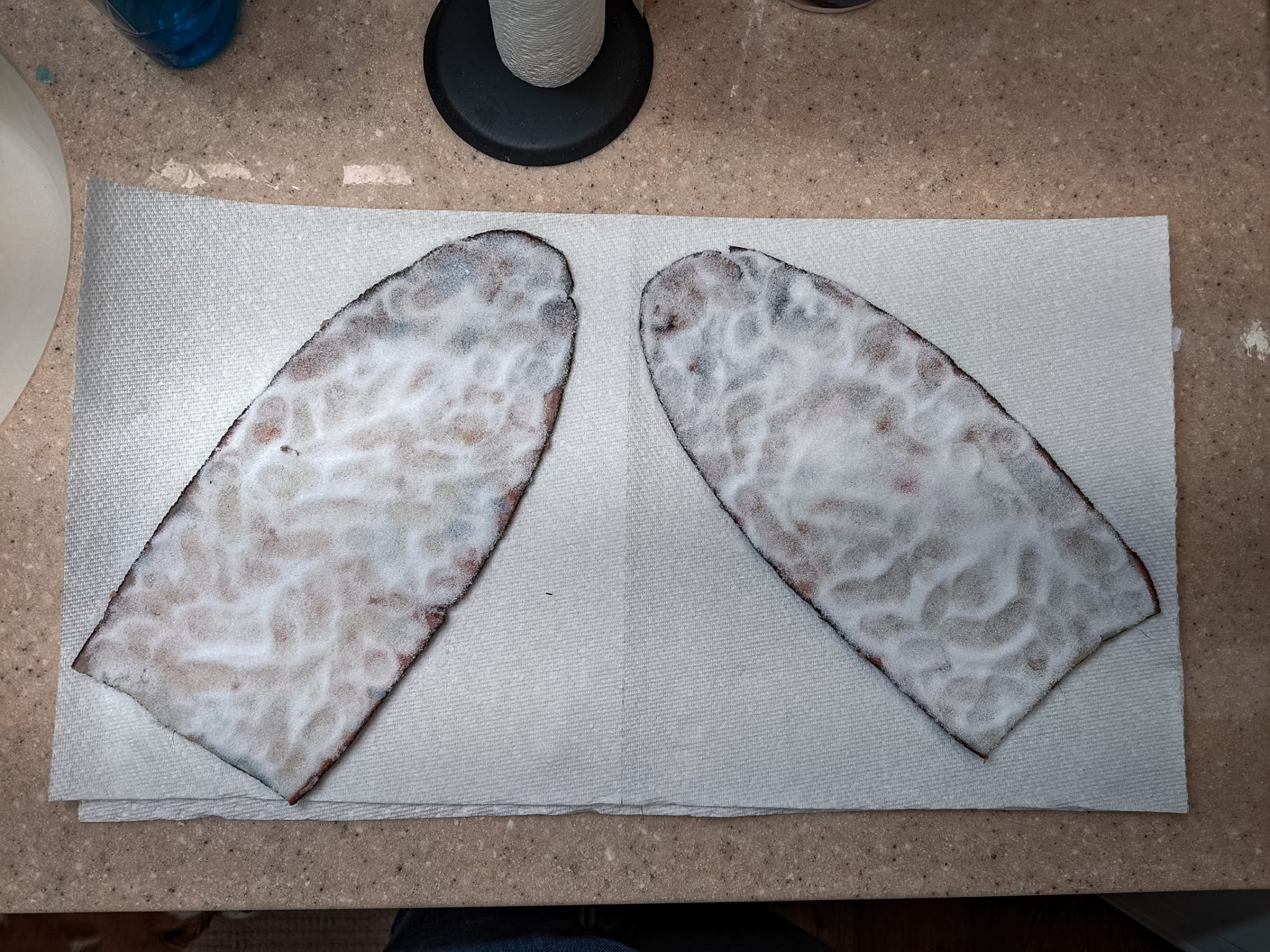

First, I thoroughly salted the flesh side of the tail halves with regular table salt and let them sit for 24 hours to dry out. After that, the tail was pretty dry and stiff.

Then, the halves went into a bucket of warm water for another 24 hours to rehydrate.

With the tail thoroughly salted and rehydrated, it then needs to be washed with dish soap to remove any remaining salt and beaver grease.

With the prep work finally done, I decided to go with the alum tanning process (aluminum sulfate and salt) because it seemed easiest and I could get the granulated alum at the grocery store.

I added the tails, granulated alum, and salt into a bucket of clean water with a 1-to-2 ratio of alum to salt. Then it soaked for 72 hours. Told you — lots of waiting.

At this point, I was three days in and the tail pieces were beginning to firm up and feel like leather, but I noticed the edges were starting to develop a slight curl.

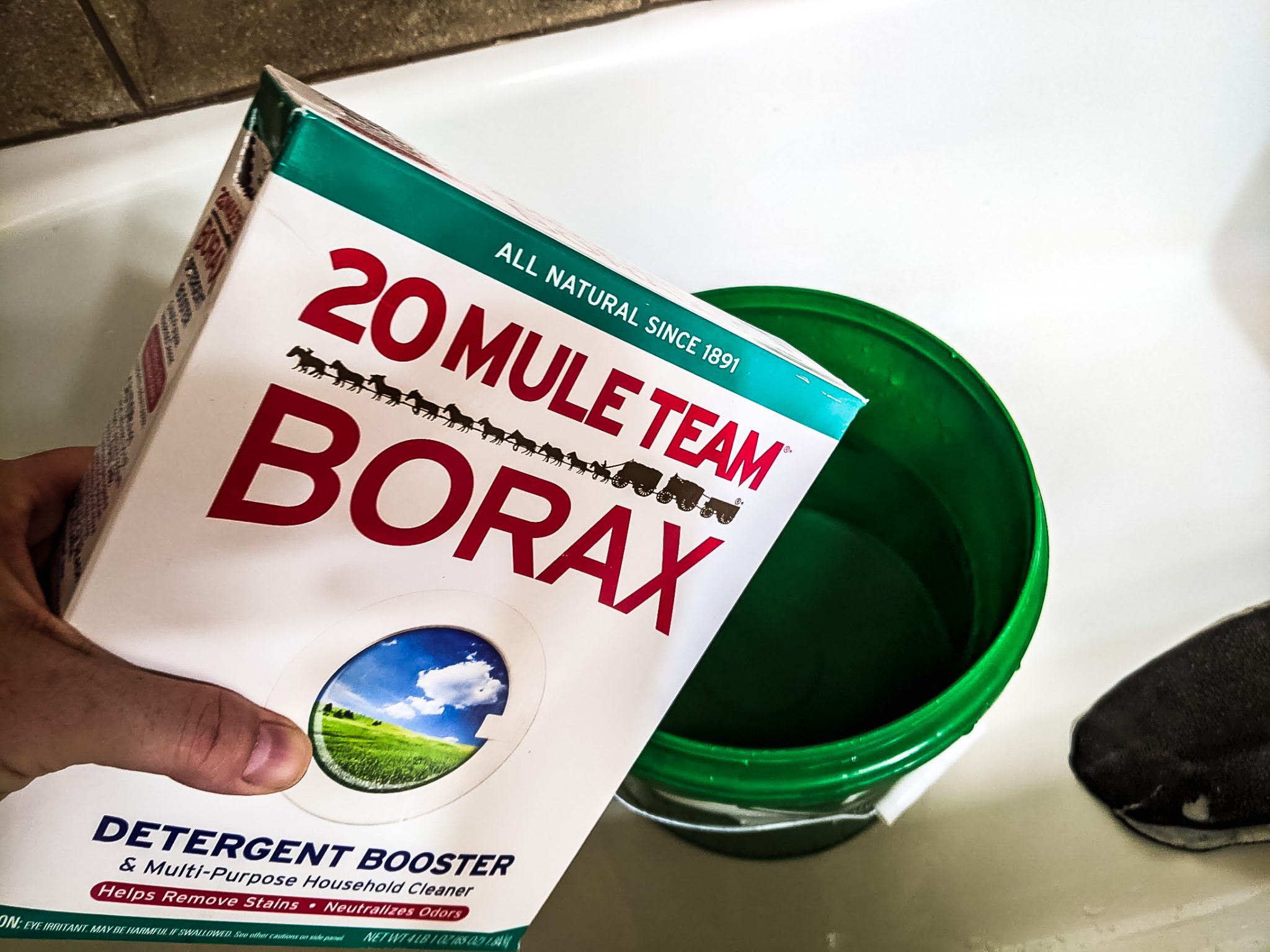

Next, the acidic alum has to be neutralized with a base. Borax works well. I dumped the bucket, filled it with some more water, added the tail and the Borax, and stepped away to wait for another 24 hours.

That was it for the tanning process and the pieces were ready for their final drying stage.

RELATED – Wild Hunting Tactics: How 7 Apex Predators Do What They Do Best

The Final Results

I set them on some paper towels and then left for a week to visit family out of state, which wasn’t the best idea. When I got back, the pieces were definitely dry, but the result wasn’t what I was expecting — they were rock hard and severely curled at the edges. Plus, little puddles of beaver grease had accumulated in places.

I wiped up the grease and worked the pieces back and forth in my hands and over the edge of a counter to try and loosen them up into something close to pliable. The edges were rock hard and there was no way to remove the curl they’d acquired. I tried some leather conditioner to add some moisture back in.

The endeavor, I’d say, was a partial success — but I learned a hell of a lot going through the process.

Next time, I will certainly do a few things differently. I’ll be sure to use more appropriate knives and clean the inside of the tail more evenly. Leaving it to dry unattended for a week was also a bad idea. I also want to consider taking this guy’s advice, do some better knife work, and leave the skin as one piece when filleting the tail, so it can lay flat. His method for removing the tail bone by cutting it out looks easier than the vise method, so I’ll try that, too.

I might also sandwich the leather between some iron mesh during the last step and see if that can prevent any curling that might occur.

For now, the pieces of beaver leather are sitting on top of my gun safe, occasionally driving one of my dogs crazy when she catches the scent. Hopefully, the results of my next attempt will be more than just a learning experience and can be made into something useful.

If you come into the possession of a few beaver tails and, like me, have no tanning knowledge and don’t want to risk ruining the leather, you can trim it up according to the directions on the Specialty Leather Productions site, freeze it, and mail it to them. They’ll tan it and send you back perfect beaver leather for $6.50 per half.

READ NEXT – Wolves in Northern Minnesota Helping Moose, Eating Beavers

Comments