The bolt action rifle is a citizen of the world. Militaries worldwide have used and still use them. Hunters from Scandinavia to Hawaii use bolt action rifles to pursue both big and small game. Americans love our bolt actions so much that we’ve entered into decades-long pissing matches about which ones are better and why.

It is the final form of the precision rifle (though some will argue that these days, there are semi-autos that are just as capable), which is saying something considering the basic design dates back to the 1820s. That’s before things like the sewing machine, the telegraph, and the revolver came around. Hell, Solymon Merrick didn’t patent the wrench until 1835.

Let’s take a good look at bolt-action-evolution highlights, from Dreyse through the 19th century to the inception of classic, 20th-century American hunting rifles.

RELATED — Sharps Rifle: The Original Long-Range Hunting Gun

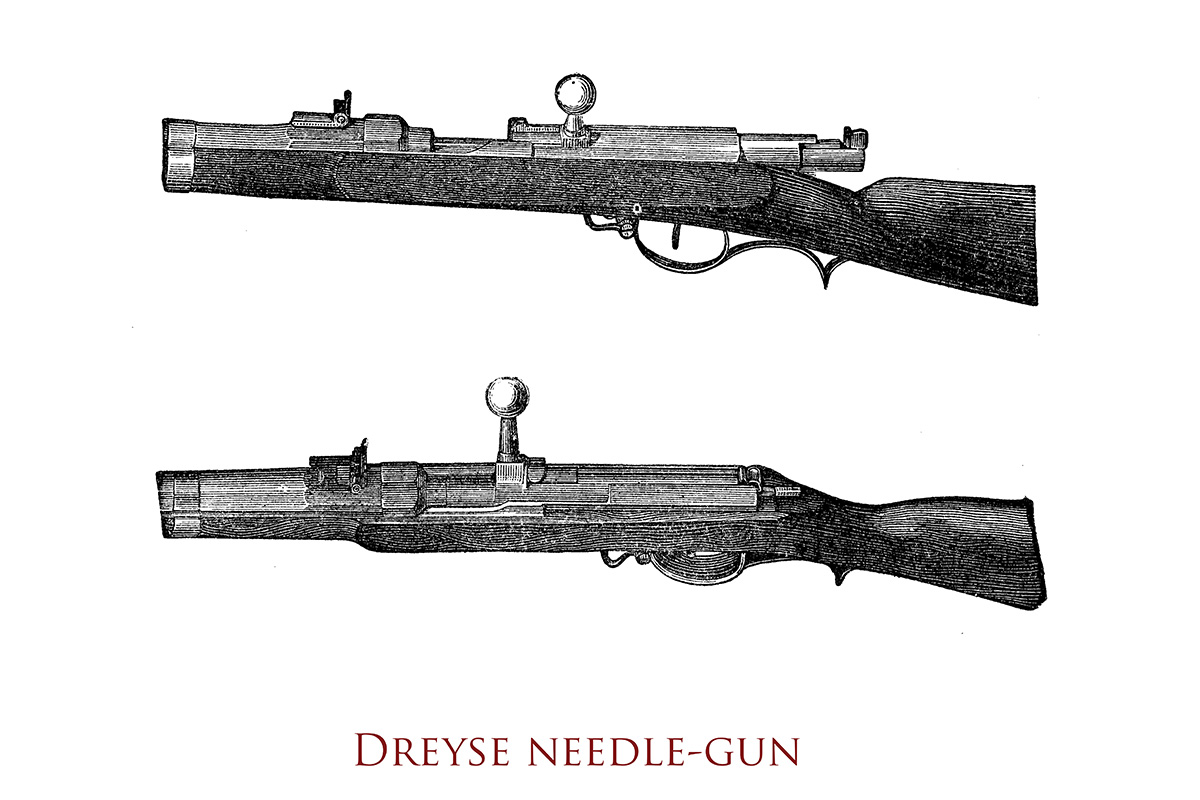

The Dreyse Needle Gun: The First Bolt Action Rifle

German firearms inventor and manufacturer Johann Nikolaus von Dreyse started the bolt action party in 19th century Prussia, and the tech rapidly spread across Europe. With the spread came quick advancements.

Dreyse got his start in the firearms world working for Swiss gunsmith Jean Samuel Pauly, the man credited with inventing the self-contained cartridge. Pauly also engineered several experimental breech-loading rifles.

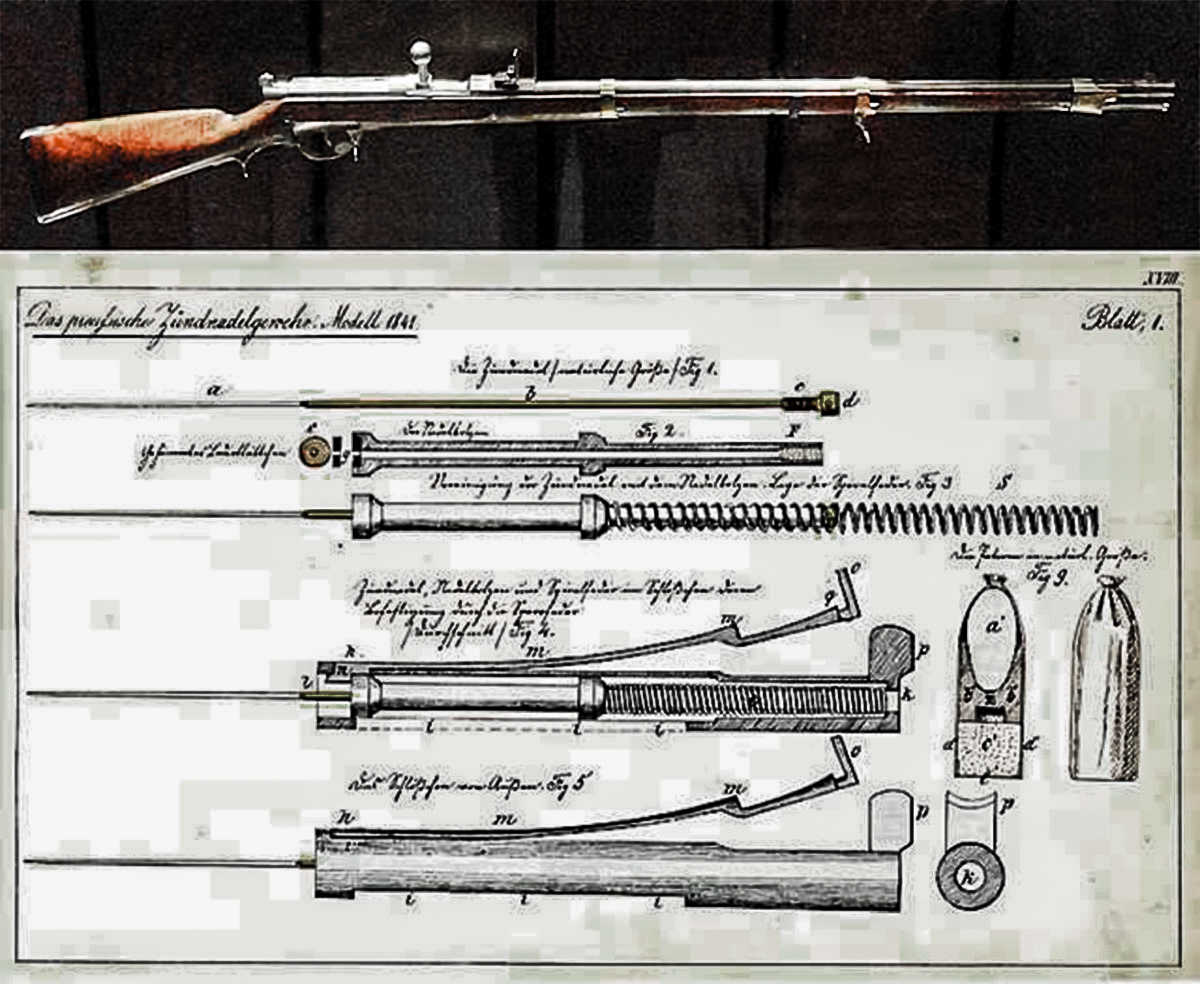

After his employment with Pauly, Dreyse returned to his native Sommerda, a district now in Central Germany, and founded a factory to manufacture percussion caps. Then he went to work on prototypes of what would become the first bolt action rifle.

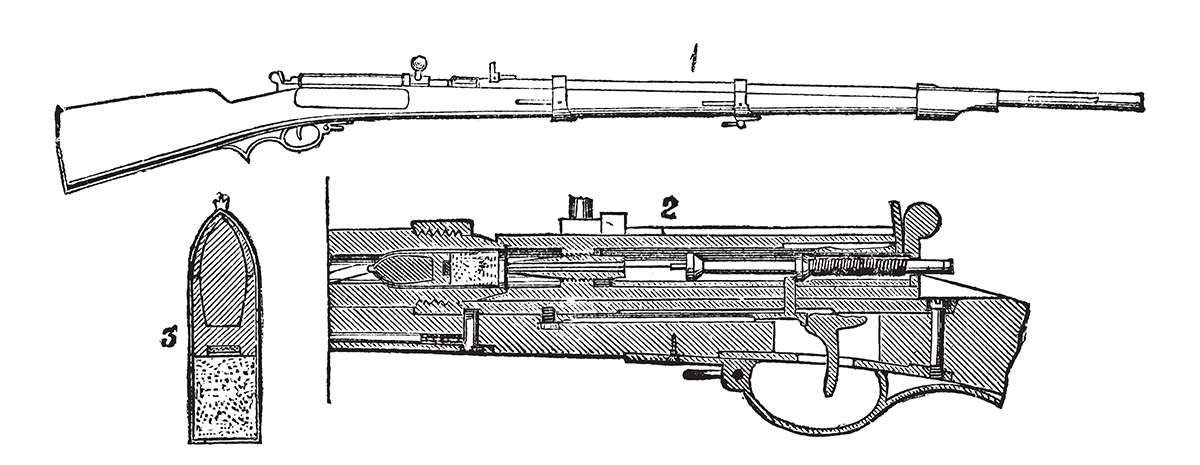

Between 1824 and 1827, Dreyse created the initial prototype of his needle gun. It was a bolt action muzzleloader and the first-ever bolt action rifle, although it bore little resemblance to the bolt guns we all know and love today.

Dreyse worked on redesigns for the next decade until he produced the Zündnadelgewehr – the needle rifle — the first successful breech-loading bolt action rifle.

Dreyse’s needle rifle used paper casings loaded with 74 grains of black powder. It fired a 15.4mm acorn-shaped bullet. Upon trigger press, the needle-shaped firing pin pierced the paper casing, traveled through the powder charge, and struck the percussion cap. The projectile left the barrel at a muzzle velocity of about 1,000 feet per second and had an effective range of about 650 yards.

A disciplined soldier could rattle off 10 to 12 rounds per minute with the needle rifle — three times as many as a trained soldier carrying a musket.

The reloading position of the needle rifle was also an advantage. Soldiers had to stand or at the very least kneel to load a muzzleloader with any kind of speed, plus you’d need a good amount of leverage, even with a clean barrel. The needle rifle could be reloaded while lying or kneeling, making the user much less of a target to enemy fire.

The increased rate of fire, combined with the ability to change fighting tactics, created devastating effects during battle. Prussian soldiers wielding Dreyse’s rifle completely overwhelmed their Austrian enemy at the Battle of Königgrätz in 1866.

For all its advancements, the needle rifle was also heavily flawed. Due to the paper cartridge, the needle rifle had no effective gas seal. When shooting from the shoulder, hot gas would leak from the breech and burn the shooter’s face after a few shots. Gas escape also limited the rifle’s chamber pressure and effective range. Plus, paper cartridges and moisture don’t get along well, especially in a combat setting.

The needle was also a huge problem. The son of a bitch was prone to breaking easily. Burning black powder enveloped the pin during each shot, which weakened it. The spring that drove the needle was also delicate and often snapped.

While the Nadelgewehr was a significant advancement, its limitations were fairly evident, especially in comparison to the French Chassepot rifle used during the Franco-Prussian war. Soon after the war, the Prussians replaced the needle rifle with the Infanterie-Gewehr 71, or Mauser Model 1871.

GOOD GEAR – Embody the Ethos of the Quiet Professional With the BRCC Silencer Smooth Roast

Highlights of Bolt Action Evolution During the 19th Century

Most of Europe was shooting at each other during the late 19th century. There was also plenty of shooting here in America. We fought the War of 1812, the Mexican-American War, the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, and the continuing American Frontier Wars in that century. All that violence fueled the fast evolution of the bolt action rifle. Plus, civilians took to bolt actions immediately for every kind of hunting a rifle was suited for.

The paper-cartridge-shooting, breech-loading bolt action French Chassepot rifle evolved into the black powder, metallic cartridge-shooting Fusil Modèle 1874 (or Gras) in response to Germany’s Mauser Model 1871. However, both the Gras and the Mauser Model 1871 were single-shot rifles.

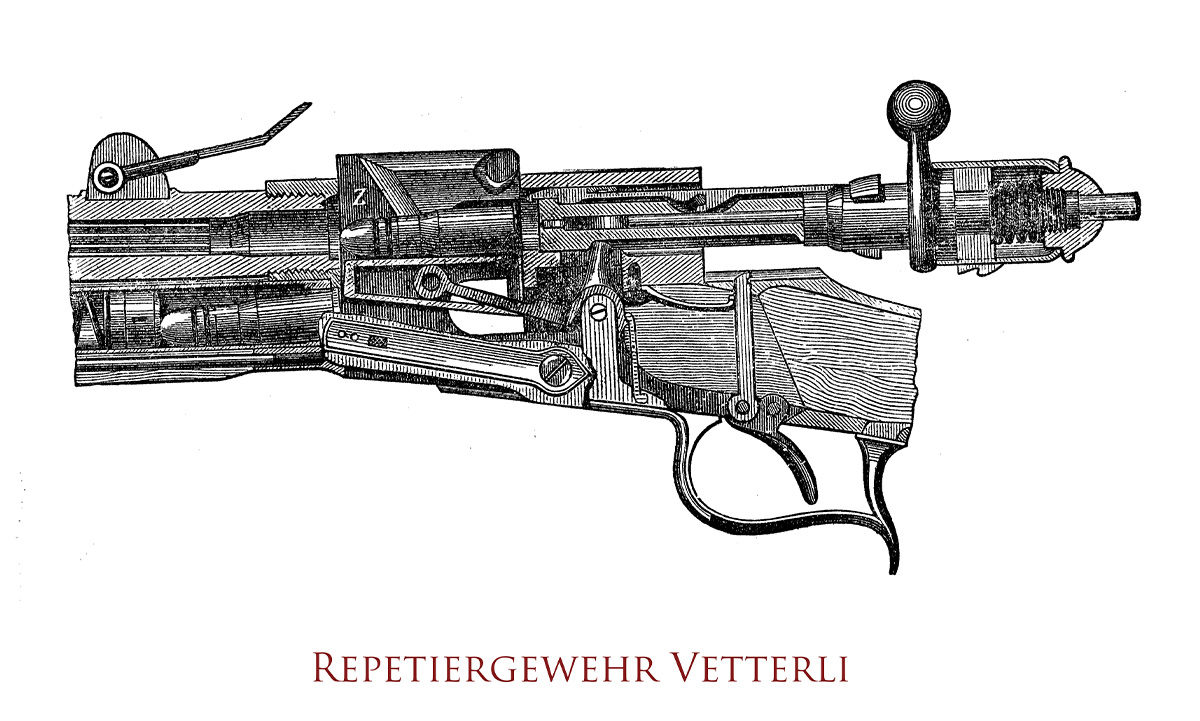

While the French and the Germans were playing checkers with bolt action development, the Swiss were playing chess. In 1869, they adopted the Vetterli rifle, the first standard-issue repeating bolt action military rifle.

The Vetterli rifle was a Frankenstein’s monster of fire superiority. It featured a Mannlicher stock and a side-loading receiver with a rising block resembling the Winchester lever actions of the day. It also borrowed Winchester Model 1866’s tubular magazine.

Within the receiver was an innovative bolt with two opposed rear-locking lugs. The Vetterli Model 1869 also had an internal cocking bolt spring. Vetterli rifles shot 10mm rimfire black powder cartridges. A good soldier could fire 21 rounds per minute. It was the superior military rifle of the era.

Meanwhile, we Americans were developing some bolt action magic of our own. In 1863, E.G. Lamson and Company patented the Palmer Model 1865 Carbine design, a rimfire rifle chambered in the Spencer 56-50 cartridge. The company sold 1,000 units to the government to support Union forces in the war effort. Unfortunately, the rifles were delivered a month after the war ended. The government offloaded the rifles to civilians at auction.

In 1879, the American bolt action hit both the frontier and the high seas shortly after Benjamin B. Hotchkiss patented the Hotchkiss rifle (not to be confused with the Hotchkiss gun, an artillery gun infamously deployed during the massacre at Wounded Knee).

The rifle was chambered in .45-70 Govt., and went through several redesigns before it was discontinued first in 1883. The Winchester Hotchkiss was issued to frontier soldiers at Fort Abraham Lincoln, among other frontier outposts, and the Navy also adopted the Hotchkiss rifle, making it the first ever centerfire, bolt action, repeating rifle used by a major military.

RELATED — Rifle Backpack Guide: Buy One That Doesn’t Suck

Turn-of-the-Century Rifles: Mauser 98 and Lee-Enfield

The turn of the 20th century saw some badass bolt actions emerge that became the godfathers of modern sporting and sniper rifles. Technology progressed to create actions that could handle the high pressures produced by smokeless cartridges.

The discussion begins, and for some ends, with the Mauser 98, which sprang from the continual evolution of the Model 1871. Some argue that the Mauser 98 is the best bolt action rifle ever made due to its revolutionary controlled-feed system and bolt design. The action features a non-rotating claw extractor, an extra safety lug, and an enlarged chamber ring.

The Mauser 98’s influence certainly isn’t up for debate. If you pull out a map and point to almost any country, chances are good that at one point, that country’s military issued the Mauser 98 or one of its descendants at some point in history.

The Mauser 98 also had plenty of influence close to home. The M1903 Springfield, the famous U.S. service rifle, is based on the Mauser 98. The U.S. government even paid Mauser royalties.

The Winchester Model 54 and the subsequent, forever-famous Model 70 are also based on the Mauser 98 design. Due to the popularity of rifles such as the Model 70 and the M1903 Springfield, many more modern bolt actions are descended from the Mauser 98.

In 1895, the Brits gave us the Lee-Enfield, the rifle that grew famous for the “mad minute.” Soldiers in the British Army would crack off as many rounds as possible with their Lee-Enfield in 60 seconds. The rifle’s detachable, 10-round box magazine contributed to the firing speed, although it was controversial at the time because of the chances of soldiers losing it.

Lee-Enfield rifles were also designed with a short bolt throw, with the bolt knob situated just behind the trigger when the action is closed, setting up the rifle for smooth, fast cycling. A good rifleman could fire 20 to 30 accurate rounds in one minute, which influenced the design of other short-throw bolt actions.

The Lee-Enfield evolved nine times, terminating with the Rifle 7.62 2A1 which was produced from 1962 to 1974.

There was a time when the sun never set on the British Empire. While times have changed, the sun hasn’t metaphorically set on the Lee-Enfield. It’s the second-longest-tenured service rifle in history, and is still used by Bangladesh police.

While the Mauser 98 gets more acclaim, both actions were linchpins of bolt action evolution and profoundly influenced the inception and development of classic American bolt action hunting rifles.

GOOD GEAR – Keep Your Coffee Hot or Cold With the BRCC YETI Reticle Rambler Mug

Winchester vs. Remington and Controlled Feed vs. Push Feed

Hunting Americana owes a lot to long-time competitors Winchester and Remington. The companies’ storied rifle design battle created a decades-long pissing match among hunters and shooters.

In 1937, the Winchester Model 70 — the rifle dubbed “The Rifleman’s Rifle” — hit gun store shelves. Thanks to famous outdoorsmen and writers like Jack O’Connor, who preferred his chambered in .270 Win, the Model 70 became one of the world’s most popular bolt action rifles.

Winchester earned the respect of outdoorsmen like O’Connor with the pre-’64 Model 70. The trigger was smooth, and the rifle’s controlled-feed action, which was modeled after the Mauser 98, made it one of the most reliable and accurate actions ever barreled. It was so reliable and accurate that famous Vietnam-era sniper Carlos Hathcock wielded a Model 70 chambered in .30-06 Sprg through the jungles of Vietnam.

According to some gun experts, the Model 70 went on the slide in the 1950s. Then, in 1964, Winchester switched from the legendary controlled feed to a push-feed system. It caused a ripple among Model 70 aficionados.

Some say the pre-’64 action is far superior. Others, like Jack O’Connor, weren’t as willing to make that claim. He said the action was stronger in the post-’64 rifle, even though it traded the original claw extractor for a wedge-shaped extractor.

In 1992, Winchester returned the Model 70 to its pre-’64 controlled-feed glory, and marketed it as the Classic model. Browning acquired Winchester in 2006, and sadly moved Model 70 production to Portugal.

Meanwhile, Remington had the Model 30, which was based on the Enfield action, which was used by both American and British forces during World War I as the M1917 and the P14. The Model 30 eventually evolved into the Model 721 and Model 722, which were released in 1948, although both rifles’ tolerances weren’t tight enough to compete with the accuracy and reliability of Winchester’s Model 70.

Remington continued pushing the envelope of their bolt action firearms with the leadership of head designer Mike Walker. In 1962, Remington unveiled the Model 700. Unlike the Model 70, the Model 700 featured a push-feed system with a c-clip extractor and a spring-loaded ejector.

Model 70 diehards claim the 700’s design is unreliable and leads to jams. However, the U.S. military considered it reliable enough to build two different sniper rifles on the Model 700 action — the M24 (Army) and the M40 (Marines). The rifle’s range of chamberings, reliability, and accuracy made the Model 700 nearly ubiquitous. It is the best-selling bolt action rifle ever manufactured.

Remington filed for bankruptcy in 2020 and was acquired by a new company, RemArms. Unfortunately, the acquisition put the Model 700 temporarily out of production. But as of September 2022, RemArms was again rolling the Model 700 on its assembly lines.

While each action has its advantages and disadvantages, the Winchester/Remington pissing match is over minutiae. Both companies have produced accurate, reliable rifles in the Model 70 and the Model 700.

RELATED — 338 Lapua: A Beastly Long-Range Rifle Cartridge

Modern-Day Bolt Action Rifles

The modern rifleman has a cornucopia of bolt action rifles to choose from, a near embarrassment of rimfire and centerfire bolt action riches. Most of those centerfire riches are direct descendants of classic bolt action designs — the Mauser 98, Lee-Enfield, Model 70, and Model 700.

Because modern machining has tightened tolerances and increased accuracy, quality exists throughout brand names. And with the advent of shouldered, pre-fit barrels and aftermarket action upgrades, hunters and shooters often build their own high-quality semi-custom bolt action rifles.

Bolt action rifles still dominate the world of snipers and long-distance precision rifle shooting. Their mechanical simplicity, reliability, accuracy, and increased velocity compared to semi-automatic actions keeps them running that game. That won’t likely change anytime soon.

GOOD GEAR – Launch Your Mornings Into Orbit With the BRCC Space Bear Roast

Long Live the Bolt Action Rifle

Military and sporting history wouldn’t be what it is without the bolt action rifle. Thanks to the ingenuity of a 19th-century Prussian gunsmith and the countless militaries that begged for fire superiority, we have an action that’s still effective for engaging enemies and dropping game animals.

READ NEXT — 5 Fabulous Hunting Rifles Ready To Punch Tags Next Fall

Comments