The evolution of a film genre usually happens gradually, with different films offering incremental innovations or outside-the-box thinking until they all add up to a significant gear shift. After all, genre fans are genre fans for a reason: They like the formula. But every so often, when Hollywood forgets what a genre is all about for a few years, one momentous movie can come along and hit the reset button. That’s exactly what Dances With Wolves did for Westerns back in 1990.

Westerns were dead in the ’80s. Silverado (1985) was pretty cool. Clint Eastwood made Pale Rider in ’85, but he also made shit like Honkytonk Man and that movie with the orangutan. I know a lot of people like Young Guns, and I guess I get it, but I hate that movie. I thought it was because I can’t stand Emilio Estevez, but it’s more than that. YG has a buoyant energy, but the story and action are simultaneously dead tired — like somebody rubbed a whole lot of cocaine on the gums of a really old dog.

The genre didn’t need movies with casts full of rising stars. It needed to be elevated. And it took an actor at the top of his game, one who was practically a cowboy himself and possessed a deep love of Westerns, to make it happen.

Why It’s So Damn Good

Wolves was a passion project for star and director Kevin Costner that the studio wasn’t confident would work at all. Of course, Wolves went on to become the highest grossing Western of all time and brought home a stunning seven Oscars with 12 total nominations (Costner won a statue for Best Director, but was also nominated for a Best Actor award for his portrayal of 1st Lt. John Dunbar).

It made Costner a huge star, began a Western movie renaissance, and also showed everyone that there are still plenty of stories to be told from this endlessly captivating era of history. And it did more than that. Its success inspired the industry to try new things with a genre that dates back to the very beginning of motion pictures, and to give filmmakers the necessary budgets to do so.

If there had been no Dances With Wolves, it’s likely Quigley Down Under (1990) would have set the tone for Westerns in the decade, which may not have been terrible — but we likely wouldn’t have gotten Unforgiven, Legends of the Fall, Tombstone, Wyatt Earp, or Far and Away in the ’90s, and perhaps the Coen brothers might never have attempted their outstanding remake of True Grit a few years later.

It raised the general bar for Westerns and Western-adjacent movies, and while not every cowboy movie released since then has been good (looking at you, The Quick and the Dead), there have been an awfully lot of great ones.

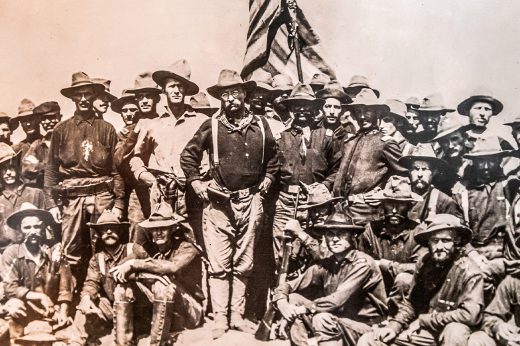

Instead of barren, spaghetti Western desert settings with a shit-splat clapboard “Old West” town full of threadbare archetypes, Wolves has an epic scale. Its lush and varied environments create the backdrop of a story that’s simultaneously uncomplicated, character driven, and emotionally complex. The costumes are tremendous, which means they don’t look like costumes at all.

The breathtaking landscapes of its South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, and Wyoming filming locations provide a ton of natural beauty, with John Barry’s unforgettably soaring score bringing it all together. The movie just looks gorgeous from beginning to end — the kind of film that gave people a reason to buy a laserdisc player.

While Wolves doesn’t nail all the time period’s details (like why the Lakota tribe Dunbar falls in with has no experience with — nor do they possess — any firearms in 1863), authenticity was still important. This was the first movie to use the actual Lakota language, which required a lot of time and effort from the cast and their language coaches, producing extraordinary results. Wolves also features an accurate depiction of how the Plains Indians once hunted buffalo on horseback with bows and arrows.

All of that is just dressing for a wonderful story about loss and utter devastation in the wake of westward expansion with a cast of multifaceted characters and circumstances that seem cut-and-dry at first blush but are revealed to be quite nuanced.

The Native American lifestyle is depicted as mostly idyllic, but it’s not perfect by any means. The Pawnee are depicted as mercilessly violent compared to the largely peaceful Lakota, just as the open-minded and righteous Dunbar is sharply contrasted by the heartless soldiers who follow him. It’s all oversimplified, but it’s also a movie.

Wolves was one of the first Westerns to really show a bit more of how rough life was in the 1860s, too. Everything is dirty, and the violence is unglamorous and nasty. Plus, it has one of the best opening sequences of all time, which was seriously dark for 8-year-old me when I saw it for the first time.

A Con That’s a Pro?

The biggest failing of this movie may be its depiction of the US soldiers at the end. As complex as the Native Americans and Dunbar are, the soldiers who arrive at the fort are one-note, cliched bad guys.

One could argue that the soldiers’ lack of dimensionality was intentional. As established in the first shot of the movie, the audience is meant to experience the story through Dunbar’s eyes. By the time the troops show up, he’s mentally so far away from the war and his life in the army that you almost forget he’s still a soldier, too.

You feel like he didn’t do anything wrong at all, let alone anything worthy of a hanging — but by the letter of the law, he’s a deserter. The soldiers aren’t so much characters as they are a collective representation of what the US government did to the native people.

But, man, the movie really makes you hate those soldiers.

First, they shoot Dunbar’s beloved horse with no provocation. Then, you absolutely want to strangle that asshole with the red beard who uses Dunbar’s journal for ass paper. At every opportunity, they beat the shit out of him (seriously, Dunbar racks up like 10 concussions from rifle-butt beatings in the last half hour of the flick), and their presence in that fort, which Dunbar made his romantic frontier home, feels like a violation.

By the time the soldiers start taking pot shots at Two-Socks as a helpless Dunbar is being carted off for execution with the sad music swelling, you’re like, “OK, movie. You’re really — you’re pushing it a little.” But as obviously manipulative as it is, it certainly evokes an emotional reaction, even 30 years and many viewings later.

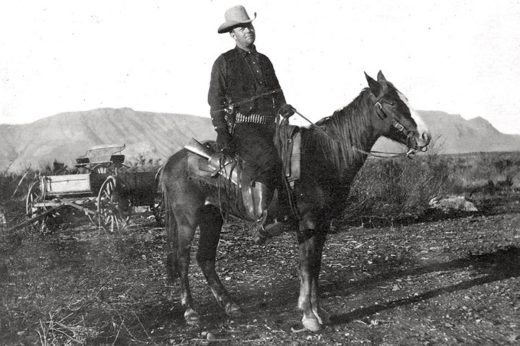

There’s also an authenticity to the film that, I hate to say, you can generally only find in pre-CGI movies. For one thing, all the horse riding in the battle scene and during the landmark buffalo-hunting scene looks so good because there were a bunch of guys really riding horses. Costner did all of his own riding, too, including riding bareback while shooting a Henry rifle.

It took a full day for the crew to reset during the filming of the buffalo stampede because the herd would run for about 10 miles every time it got going. It simply took all day for the wranglers to herd them back into position for another take.

The animatronic buffalo for the hunt scenes and the fake dead buffalo were so realistic that the movie caught flak from animal rights groups until they saw how the props were built. Somebody even called police when they saw the field of skinned buffalo, who responded with guns drawn, ready to arrest the crew members as poachers. Everyone had a good laugh after taking a look at the fake carcasses.

If you’ve never seen this classic, or if it’s been a few years, Netflix has added Dances with Wolves to its lineup this month. You aren’t going to walk away from it with a ton of warm and fuzzy feelings, but this movie holds a special kind of magic that will last for as long as movies endure.

Ron Good says

Great info. Thank you. Fun and satisfying to read.