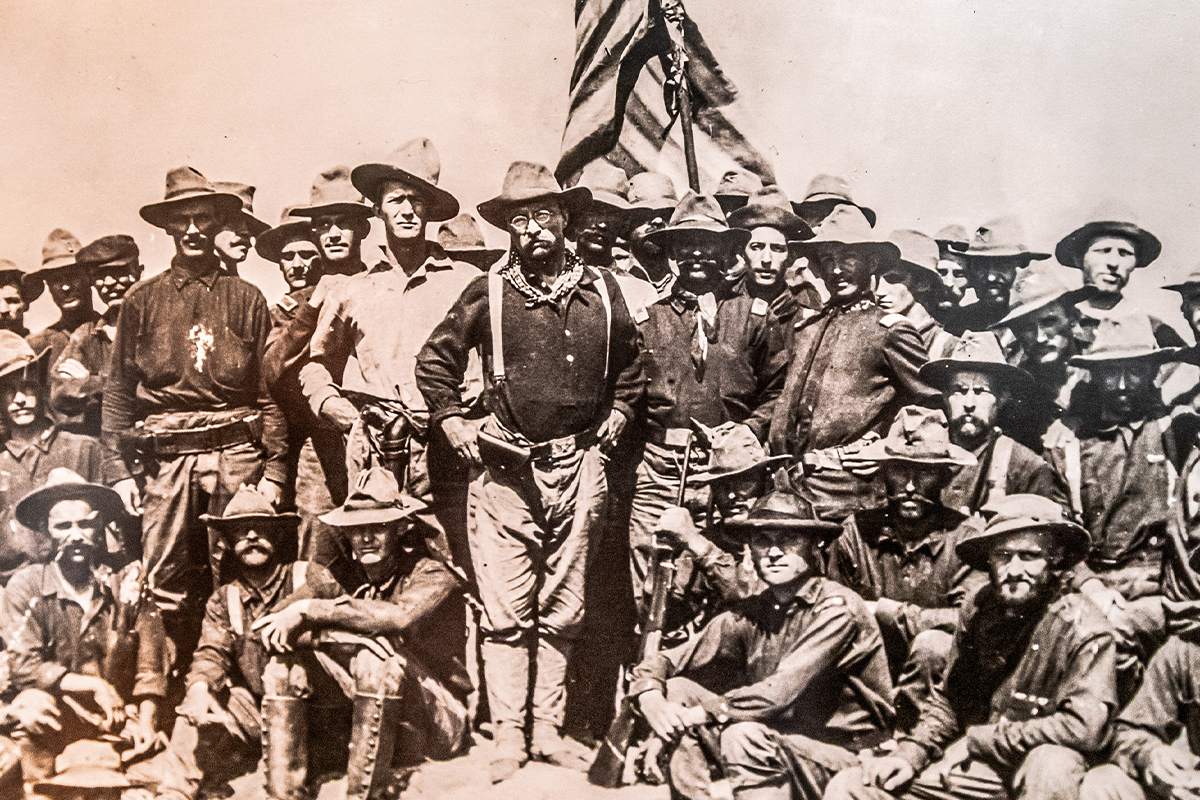

Generations of American schoolchildren have learned about Theodore Roosevelt leading the Rough Riders as they charged to victory up San Juan Hill during the Spanish-American War. The mental images of Roosevelt hooting and hollering his way up that Cuban hill on horseback cement a wildly rugged and heroic image of the man who eventually charged his way straight into the White House.

However, There’s a lot more to the story of T.R.’s Rough Riders, and Roosevelt wasn’t the only wildly rugged hero who forged forward to victory that day.

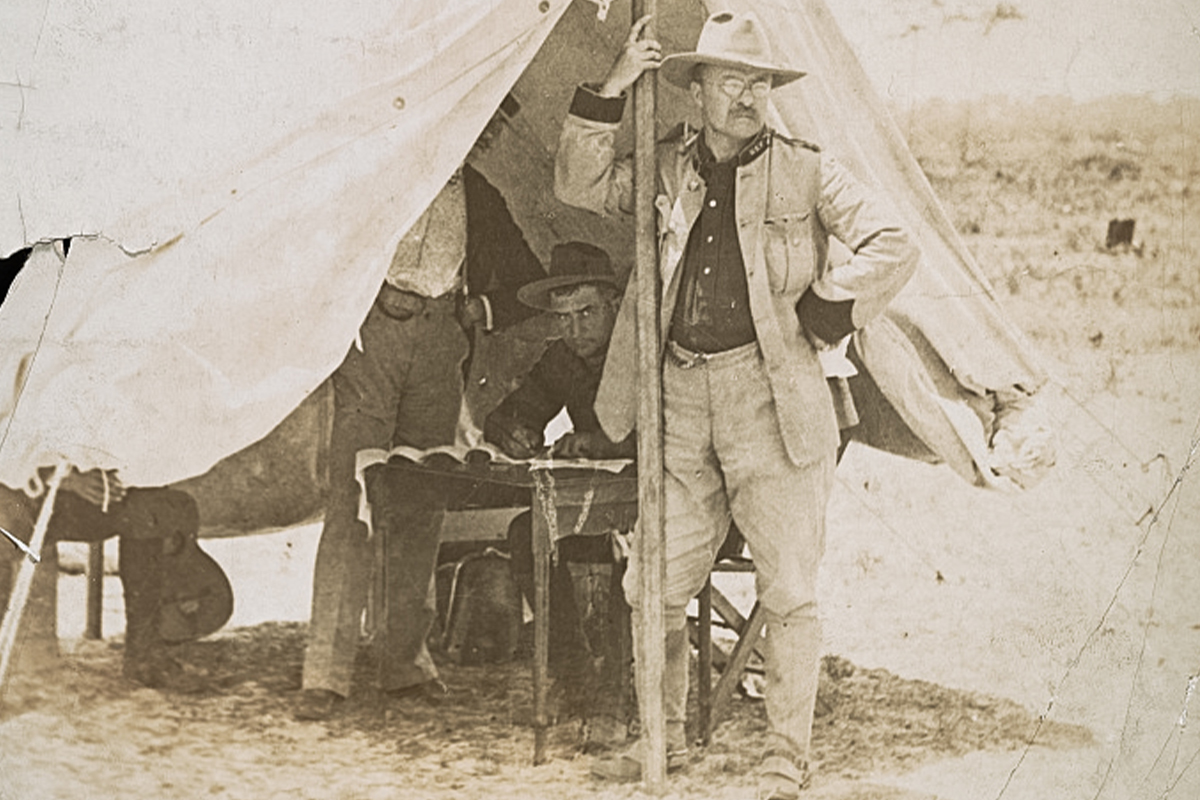

Roosevelt is known now and was likewise known in his time as a larger-than-life personality, a man who honed his body through hard work, was at home in the wild and rugged spaces of the American West and was a through-and-through American patriot. He was the center of attention in any room he occupied.

He also regularly chose to surround himself with men he admired.

Shortly after a massive explosion sank the battleship USS Maine in Havana Harbor in February 1898, killing more than half of the 400 crew members, Roosevelt, who was serving as Assistant Secretary of the Navy, left his position. He walked away from his cushy civilian desk job to form his own cavalry unit, the First United States Volunteer Cavalry, better known as Roosevelt’s Rough Riders.

Roosevelt’s vision of his volunteer cavalry unit was one filled with rough-and-tumble men unafraid of getting their hands dirty, the kind of manly men Roosevelt admired.

GOOD GEAR – Explore the Unkown With BRCC’s Beyond Black Roast

Roosevelt Takes a Supporting Role

Although T.R. is forever the Rough Riders’ figurehead, he was only second in command. Secretary Russell Alger offered Roosevelt the command, but he deferred to someone with more military experience.

“If I had taken it, being entirely inexperienced in military work, I should not have known how to get it equipped most rapidly, for I should have spent valuable weeks in learning its needs,” Roosevelt later wrote in his 1899 book, The Rough Riders.

Instead, the command was given to Col. Leonard Wood, army surgeon, McKinley’s personal physician, and Medal of Honor recipient for his role in the Apache Wars. Roosevelt assumed the position of Lieutenant Colonel.

Roosevelt took his position very seriously, telegramming an order to Brooks Brothers for an “ordinary cavalry lieutenant-colonel’s uniform in blue Cravenette” to ensure he looked the part.

READ NEXT – Dead Drift: Fly Fishing Apparel You Want To Wear off the Water

Who Were the Rough Riders?

With war about to go down in the Caribbean, Roosevelt set up an enlistment table at the Menger Hotel and Bar in San Antonio, Texas, just a handful of yards from the Alamo. T.R. had first visited the place while he was in Texas on a javelina hunt in 1892, and he deeply admired Southwesterners. He was more than satisfied with the men who showed up to volunteer.

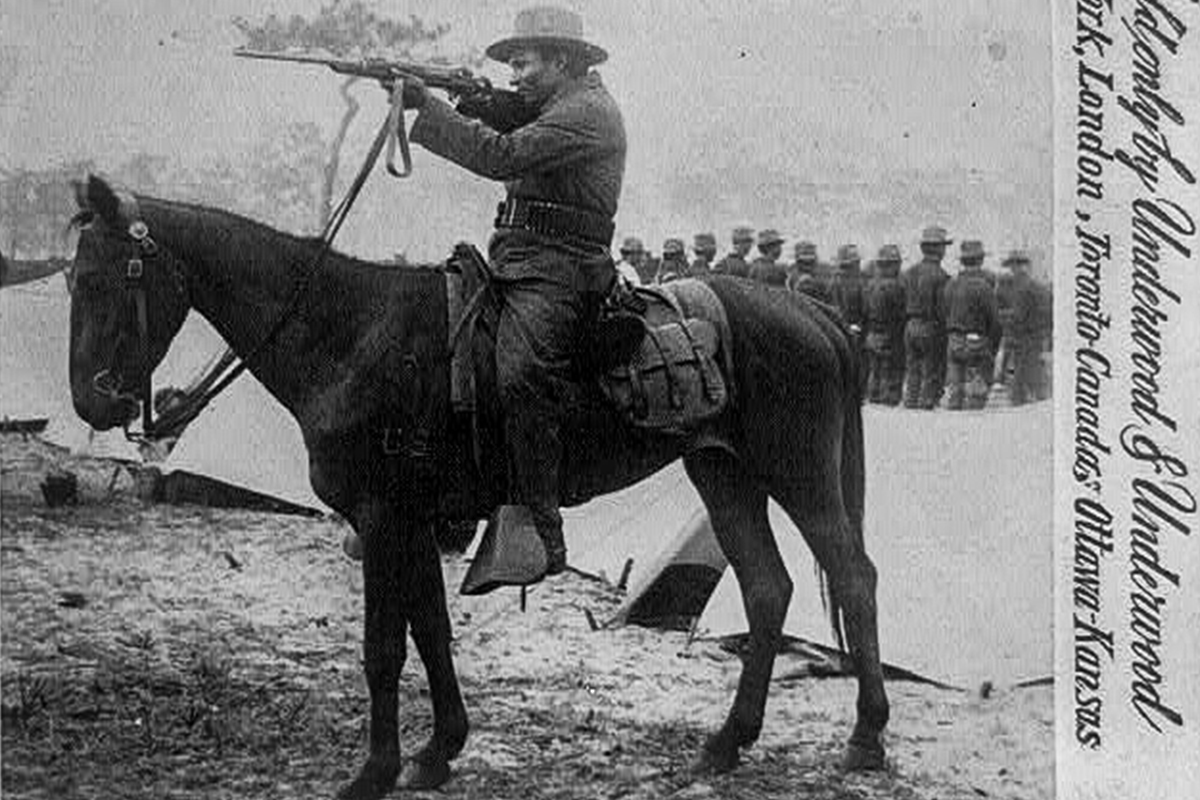

“Recruits must be a good shot…able to ride anything in the line of horseflesh…a rough and ready fighter, and above all must have absolutely no understanding of the word fear,” Roosevelt said.

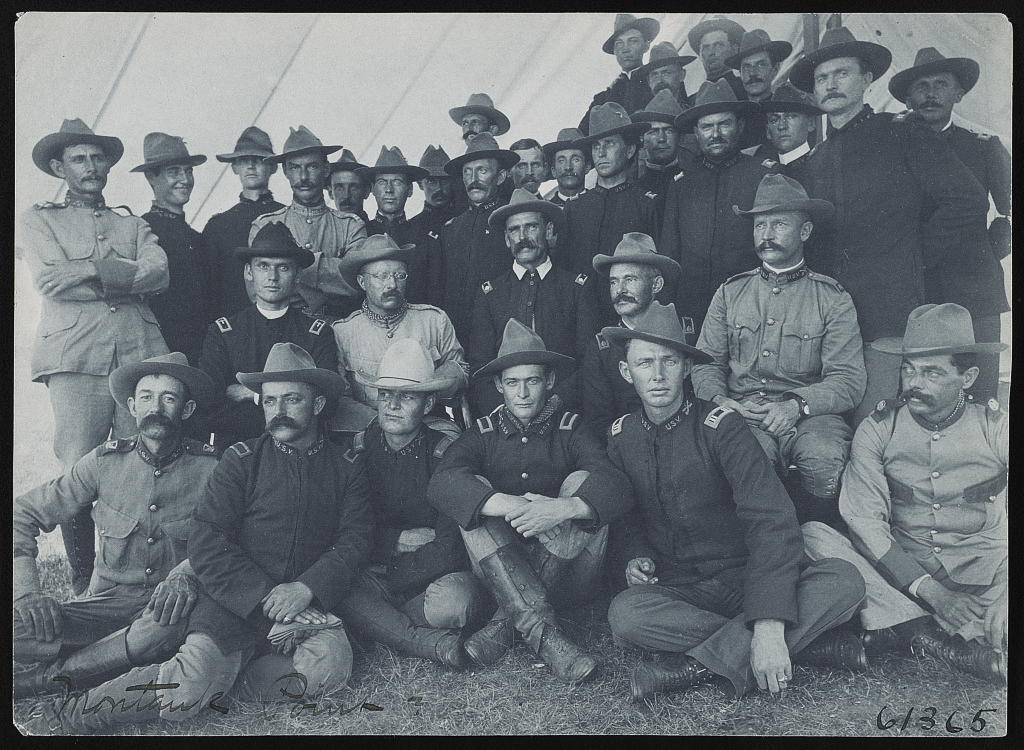

Roosevelt sifted through 23,000 applications before whittling them down to the 1,060 men who would make it into the Rough Rider ranks. When all was said and done, the list included men from all 45 states, four U.S. territories, and 14 countries.

“The life histories of some of the men who joined our regiment would make many volumes of thrilling adventure,” Roosevelt wrote.

The Rough Rider ranks were filled with harsh, seasoned, manly men with swagger. T.R. was a former wispy asthmatic weakling with a sunken chest who turned himself into a robust, athletic, rugged outdoorsman through hard work and arduous training. He chose to surround himself with the same icons of manhood that he admired.

His band of fighters epitomized everything that Roosevelt considered noble and masculine. The free and vigorous life of the Western cowboy was the antidote to what Roosevelt believed was the effeminizing and softness of modern society’s upper-class Easterners.

“They were a splendid set of men, these Southwesterners — tall and sinewy, with resolute, weather-beaten faces, and eyes that looked a man straight in the face without flinching,” Roosevelt wrote.

“In all the world, there could be no better material for soldiers than that afforded by these grim hunters of the mountains, these wild rough riders of the plains. They were accustomed to handling wild and savage horses; they were accustomed to following the chase with the rifle, both for sport and as a means of livelihood.

“They were hardened to life in the open and to shifting for themselves under adverse circumstances.”

While most Rough Rider volunteers hailed from Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and Oklahoma, more than a few polished Ivy League athletes were in the ranks.

And while it may seem absurd to toss a bunch of college football and polo players into the mix of lawmen, cowboys, miners, frontiersmen, and Native Americans, it actually made perfect sense.

High-level athletes are no strangers to focus, hard work, or bodily discomfort. You don’t become a football champ (especially in the days before protective gear was standard) without being extra freakin’ tough, and those boys proved it on the battlefield just as they had on the gridiron.

“The same spirit that once sent these men down a white-washed field against their opponents’ rush line was the spirit that sent Church, Chaning, Devereaux…and a dozen others through the high hot grass at Guasimas, not shouting as their friends the cowboys did, but each with his mouth tightly shut, with his eyes on the ball, and moving in obedience to the captain’s signals,” journalist Richard Harding Davis wrote.

GOOD GEAR – Conquer Your Taste Buds With BRCC’s AK-47 Espresso Roast

How the Rough Riders Got Their Name

Roosevelt’s regiment has rarely been referred to by its official title. The public promptly christened them the Rough Riders, and that is the name that made it into most high school history textbooks.

“At first we fought against the use of the term, but to no purpose; and when finally the Generals of Division and Brigade began to write in formal communications about our regiment as the ‘Rough Riders,’ we adopted the term ourselves,” Roosevelt wrote.

Richard V. Oulahan, a reporter with New York’s Evening Sun, is commonly credited with coining the term.

And while Roosevelt claimed to have resisted the moniker, Oulahan later attributed the nickname to Roosevelt himself.

“[Roosevelt] said casually that he intended to organize a regiment of rough riders. That was a slip, but upon my journalistic mind, the alliterative allurement of ‘Roosevelt’s Rough Riders’ took deep hold, and my imagination pictured it in the headlines,” Oulahan told a group of student journalists two decades after he wrote about Roosevelt’s cavalry unit.

Whether Rough Riders was an intentional branding by Roosevelt or brilliant reporting on Oulahan’s part, the nickname stuck, and generations of schoolchildren have known them as such.

RELATED – Why Theodore Roosevelt Was the Most Badass President Ever

More Like Rough Walkers

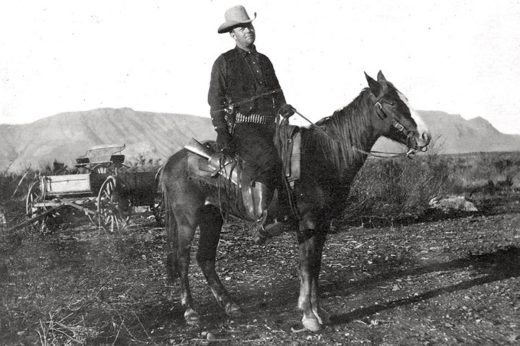

With a name like Rough Riders, it’s easy to picture 1,000 horses galloping thunderously up San Juan Hill. And although the ability to ride was a prerequisite to Rough Rider enlistment, Roosevelt was the only soldier on horseback that day, shouting encouragement and commands as his men fought their way inch by inch, crawling on their bellies through the hot, sticky Cuban mud to take San Juan Hill, also known as Kettle Hill.

They may have been a trained cavalry unit filled with skilled horsemen, but they took the Hill as infantrymen.

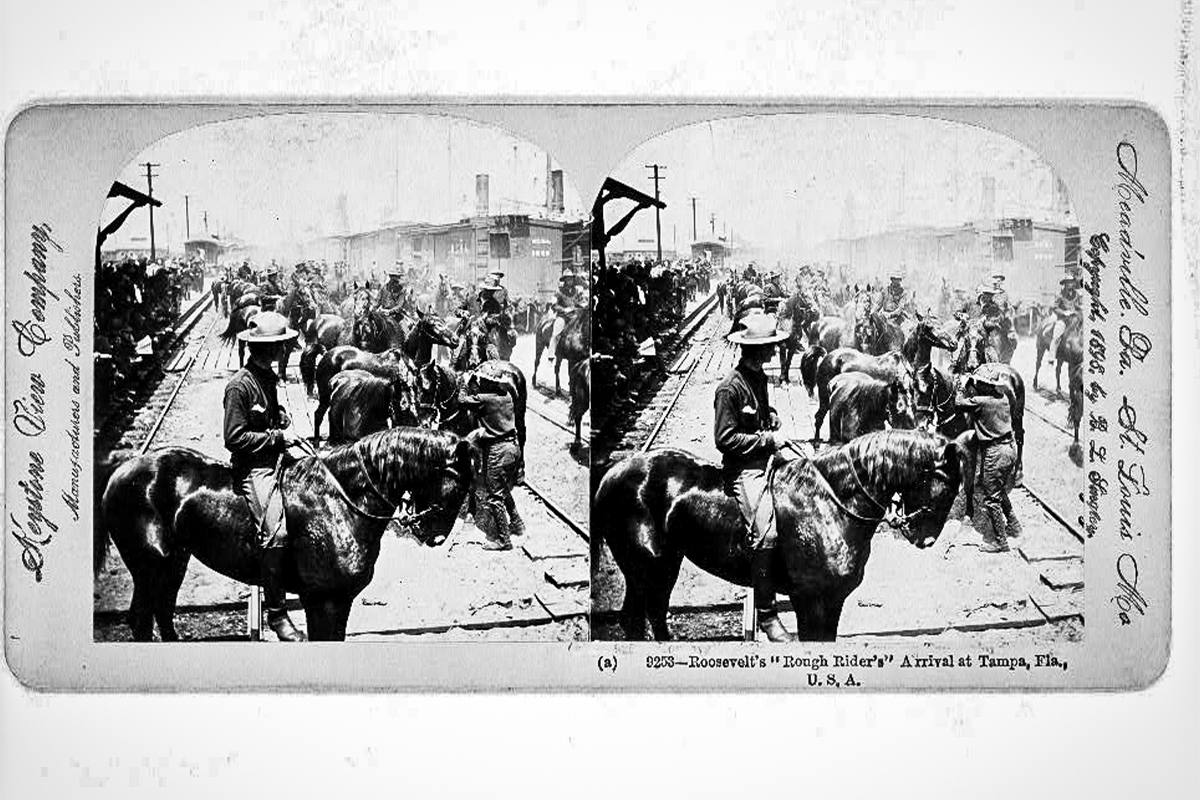

Why didn’t the Rough Riders charge to victory on horseback? In predictable military-snafu fashion, the Navy didn’t have enough ships to get the horses to Cuba. So, when the Rough Riders departed from Tampa, they were forced to leave their ponies behind.

GOOD GEAR – Fuel Your Next PR With BRCC’s Fit Fuel Blend

Legacy of the Rough Riders

Although the Rough Riders had to fight as regular infantrymen in Cuba, T.R. fought in the conflict from the back of his horse, Little Texas. Unfortunately, the horse was caught in some wire during the charge, forcing T.R. to leave him behind and continue the mission on foot.

But the horse didn’t perish in Cuba. Little Texas spent his retirement years at Sagamore Hill, the Roosevelts’ summer home in Cove Neck, New York.

A towering statue of T.R. astride Little Texas is parked outside the Menger Hotel Bar, where Roosevelt did his Rough Rider recruiting. There is another like it in Roosevelt Park in Minot, North Dakota.

Spanish forces surrendered in Santiago, Cuba, on July 17, just a few weeks after the First Volunteer Cavalry set foot on the island on July 1, 1898. The Rough Riders returned to American soil in August, disembarking at Montauk Point, New York, where they were quarantined for 30 days.

It was a challenging four months of service for Roosevelt’s Rough Riders. More than a third of the cavalrymen were killed or stricken by disease. With a 37% casualty rate, the regiment suffered the highest casualty rate of any American unit in the Spanish-American War.

Roosevelt would end up with a Medal of Honor for military valor during the Battle of San Juan Hill, although he received it posthumously in 2001, more than 82 years after his death.

A 14-foot-tall gray granite obelisk was erected in Arlington Cemetery in 1906, dedicated to the Rough Riders who didn’t make it home.

While statues and granite obelisks are fine memorials, the true testament to the courage, determination, and absolute virility of Roosevelt’s hodgepodge of some of the manliest men of his time is that the Rough Riders still capture our respect.

READ NEXT – Roosevelt’s Rough Riders Era Custom S&W Sells for $910K

Comments