Every handgun, rifle, or shotgun cartridge is a tiny bomb. The goal of every trigger press is to detonate that tiny bomb in a controlled, channeled explosion that propels a projectile or multiple projectiles. When everything goes right, the gun goes boom, and a bullet or measure of shot exits the muzzle and speeds downrange — and the clay breaks, the steel dings, the paper is punched, or the animal drops. But that requires a lot of things to go right in a precise order, and sometimes, the process goes off the rails somewhere. Things get especially gnarly when the projectile fails to leave the barrel because of a squib load or hang fire.

The die-hard trap shooters at my local club store have a cleaning rod under the awning behind the trap house. These folks shoot high-volume, and they mostly hand load their shells. With all that handloading and all that shooting, there’s a higher likelihood of squibs.

That cleaning rod is there for shooters to push the wad from a squib out of their shotgun barrels. This remedies a dangerous situation before a gun can blow up or someone gets injured — assuming the shooter recognizes a squib load when they encounter one.

The hang fire is the equally dangerous brother of the squib load. When mishandled, they can and have resulted in severe injury or death. A few seasons ago, one of my hunting partners had a hang fire when trying to clear his muzzleloader after an unsuccessful whitetail hunt. Luckily, he knew what to do, and the bullet ended up in the ground, not in a person or building.

While much of the hang fire conversation pertains to muzzleloaders, they also happen with cartridge ammunition. These days, as shooters resort more often to using off-brand factory ammo made with potentially questionable primers and powder, squibs and hang fires are more of a concern than they once were.

These are some of the most dangerous circumstances a shooter can encounter in the field and on the range. Let’s cover what exactly squibs and hang fires are, how to recognize them, and how to deal with them safely.

RELATED – Roosevelt’s Legendary Double Rifle, the ‘Big Stick,’ up Close

What are Squib Loads and Hang Fires?

SQUIB ENCOUNTER

You press the trigger on your firearm, and it fires, but it just doesn’t sound right. There’s more of a “pop” than a “bang,” and there is hardly any felt recoil. You’ve just experienced a squib load.

In the movie world, a squib is a little special effects explosive that makes it look like an actor gets shot on screen or like a bullet hits a wall. In the real world, a squib load is a cartridge that generates insufficient pressure to fire a bullet. This can happen for several reasons.

Sometimes a bad primer doesn’t generate enough of an initial explosion to set off the entire powder charge in a cartridge. If ammunition is stored improperly and the powder in the casings collects moisture, it may fail to ignite when fired, resulting in a squib. In a handloaded cartridge, the powder charge may have been mismeasured or simply too light.

Other common squib causes are malformed flash holes, light primer strikes, and improperly seated primers — each resulting in a powder charge not fully igniting.

Sometimes, this results in a projectile simply lobbing out of the muzzle with little to no energy and landing in the dirt right in front of the firing line — that’s the best-case scenario. Often, the bullet won’t even leave the barrel, becoming stuck somewhere in the bore. With shotguns firing birdshot or buckshot, the wad often gets lodged in the barrel.

If the shooter were to fire another round without clearing the barrel, it would be like firing a gun with a barrel packed full of mud — not good.

Safe handling of squibs and hang fires begins with understanding how your firearm functions under normal conditions. That means grasping what is supposed to happen during every trigger press. It also means knowing what the recoil of each firearm feels like and noting the sound of each firearm’s muzzle blast, even through hearing protection.

When you’re clear on what’s normal, there’s a greater likelihood that you’ll perceive dysfunction. Then, make sure you follow the basic rules of firearm safety.

A best practice is keeping a brass or plastic squib rod or cleaning rod with you every time you go shooting. The rod is your best tool for popping out a lodged bullet or wad.

If you think you’ve experienced a squib, wait at least a minute with the muzzle pointed downrange. Then, clear the chamber and remove the magazine.

From there, you must at least partially disassemble your firearm. For example, to remove a squib from a bolt-action rifle, remove the bolt and look down the breech to locate the bullet. Once you locate it, drive the rod down the barrel from the chamber end and tap the bullet until it comes loose and falls free of the muzzle.

Then, if you have a bore light or similar tool handy, inspect the barrel for damage. Some firearms, like many semi-auto handguns, will require a complete field stripping to get a rod down the barrel from the breech.

The reason you keep the muzzle pointed downrange at first is because, sometimes, what you think is a squib is actually a hang fire. There’s a little pop, there’s a little smoke, but there’s no shot. However, the powder might still be burning, and the projectile could still fire with lethal force. If something doesn’t sound right, never tap and rack and keep shooting. Always check the barrel for obstructions.

LEAVING YOU HANGING

You press the trigger, and nothing happens. Then, after a pause, boom! The round goes off and sends the bullet screaming through the ether. You’ve had your first hang fire experience.

A hang fire is a long delay between the trigger press and the round firing. It’s particularly dangerous because a shooter will often assume they simply didn’t chamber a round and go about remedying that — and the round will spontaneously fire.

A common cause of hang fires with cartridge ammunition is a light primer strike by a damaged firing pin. Inexact tolerances during manufacturing can distort the firing pin’s path as it slides forward toward the primer. Over time this damages the pin, which can cause it to no longer hit a primer with the proper amount of force.

This can also be the result of a dirty gun. Fouling buildup or a weakened spring reduces the pin’s normal reach. An improperly closed bolt may also cause a hang fire because the firing pin isn’t properly oriented toward the primer.

The typical delay isn’t long with cartridge ammunition, usually less than a second. But that doesn’t mean the delay couldn’t be longer.

Defective primers, incorrect primer use, malfunctioning firing pins, and dirty breech plugs cause muzzle loader hang fires. The delay is often significantly longer than cartridge hang fires, making them more dangerous.

Here’s how to handle cartridge and muzzleloading hang fires:

First, a word about what not to do. Some folks say to eject the round as soon as it doesn’t fire. Do not listen to these people; they’re endangering you and those around you at the range.

The safest place for that round is in the firearm while the firearm is pointed in a safe direction — preferably downrange. Stay behind the gun with the muzzle pointed downrange for a full minute if you’re shooting cartridge ammunition or a muzzleloader. That might seem like overkill for cartridge ammo, but it’s far better to err on the side of caution here.

If a full minute elapses and the round doesn’t fire, it’s almost certainly safe to declare it a misfire and the cartridge can be ejected and examined.

It’s important to note that squib rounds and hang fires are possible with all types of firearms.

GOOD GEAR – Ditch That Ancient Grog Cup in Favor of the Blackbeard 2.0 Mug here!

The Potential Consequences

Bad things occur when a shooter encounters a squib, doesn’t recognize it, and tries to make the gun go boom again with a projectile lodged in the barrel. On a noisy range, when firing multiple rounds, a shooter may assume the gun wasn’t chambered when they pulled the trigger, rack it, and fire again.

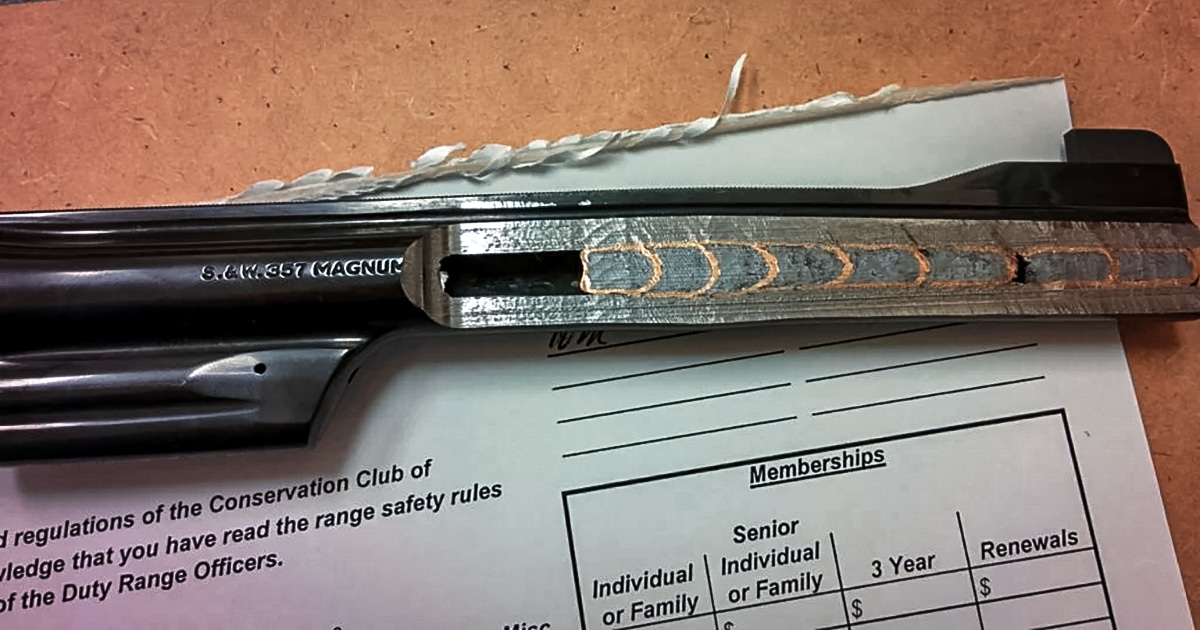

The round fired after the squib usually doesn’t create enough pressure to force both projectiles out of the muzzle. Consequently, pressure builds to extreme levels in the chamber and barrel, and something has to give — it’s usually the barrel, which can explode or burst dramatically. Sometimes, the pressure will just bulge and destroy the barrel from the inside.

In the most benign cases, the round after the squib creates just enough pressure to push both projectiles through the muzzle and clear the bore, though this can still result in damage to the firearm.

The most severe squib aftermaths result in the entire firearm blowing apart, accompanied by potentially severe injury to the shooter and bystanders. There’s no way to predict what will happen when a live round is fired after a squib, but it’s usually not good.

Hang fires are dangerous no matter the circumstances. But the danger increases when the shooter turns into Curious George or gets careless with the muzzle and starts flagging people in frustration, or the most unforgivable gun safety sin, they look down the barrel.

RELATED – 454 Casull: A Legendary Handgun Hunting Cartridge

How Common is a Squib Load?

While squibs and hang fires are dangerous, they’re not common in factory ammunition. Firearm experts file squibs and hang fires under the extremely rare column. I’ve read estimated statistics that state for every 100,000 factory ammo rounds, one is a squib.

Many high-volume shooters report experiencing only a handful of squibs and hang fires over decades-long careers. However, the probability is never zero. That’s especially true if you buy cheap ammo.

It’s important to remember that the likelihood of a squib or hang fire dramatically increases if you’re handloading your cartridges, shooting a muzzleloader, or your ammunition gets wet or even damp. So, you should know what to do when either occurs.

GOOD GEAR – If You’re Wondering What Freedom Tastes Like, Drink BRCC’s Freedom Roast

How to Prevent a Squib Load or Hang Fire

Control what you can control. Keep your firearms clean, conduct regular maintenance, and perform frequent function checks. Control also means buying decent ammo. You can’t help what goes down at the ammunition factory, but you can buy from trusted companies that produce quality products.

If you’re handloading, make sure you build double and triple checks into your systems. Be diligent in following recommended powder charges based on bullet weight, powder, and the cartridge you’re loading.

Ensure correct primer use and store components for different cartridges separately to avoid mixups. Store all ammo and reloading components in a cool, dry place. Gunpowder is hydrophilic and does not spark well when damp. If you’re committed to burning through ammo that has potentially come in contact with moisture at the range, be extra vigilant of both squibs and hang fires.

Squibs and hang fires are dangerous, but they don’t have to end with a destroyed gun or missing fingers. Know your firearms, pay attention, and follow a safe process for dealing with each.

READ NEXT – Oregon Measure 114 Could Halt Gun Sales in State for Years

Comments