In November 2020, Colorado voters passed Proposition 114 as a ballot initiative; the measure requires Colorado Parks & Wildlife (CPW) to reintroduce wolves in northwestern Colorado before the end of 2023. As the deadline for reintroduction closes in on the Highest State, tensions between reintroduction proponents and area ranchers are running high, just as they have in other states where wolves have been reintroduced.

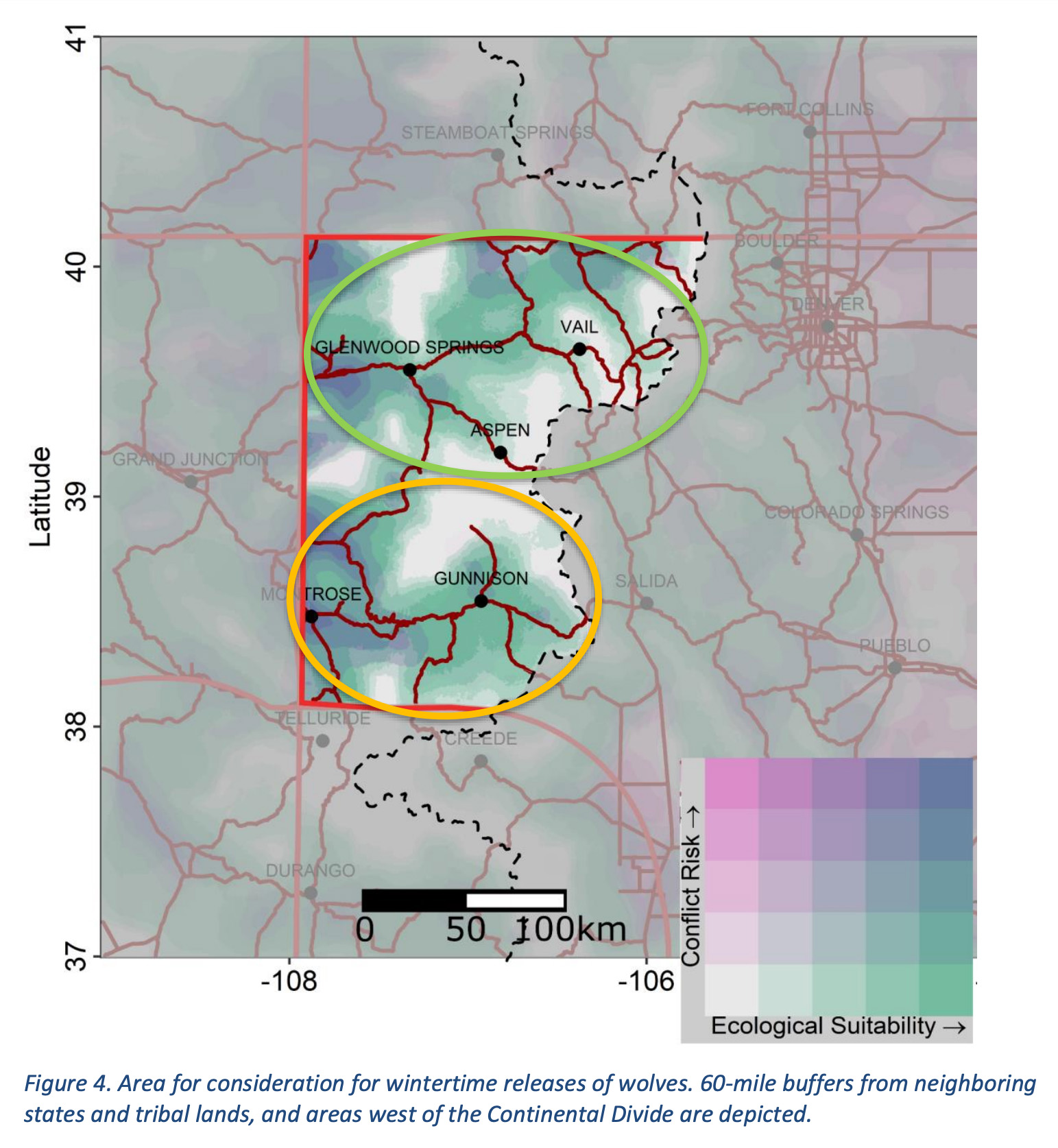

According to CPW’s 293-page reintroduction draft plan, 30 to 50 gray wolves will be transferred from Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Oregon, and Washington to Colorado’s Western Slope over the next three to five years. Officials will be working toward a minimum population of 150 to 200 wolves.

Although many consider the return of wolves to part of their historical range a win, not everyone is excited about the predator’s return to Colorado.

RELATED — There Are Gray Wolves in New York Says DNA of Hunter’s Kill

Who in Colorado Wants Wolves?

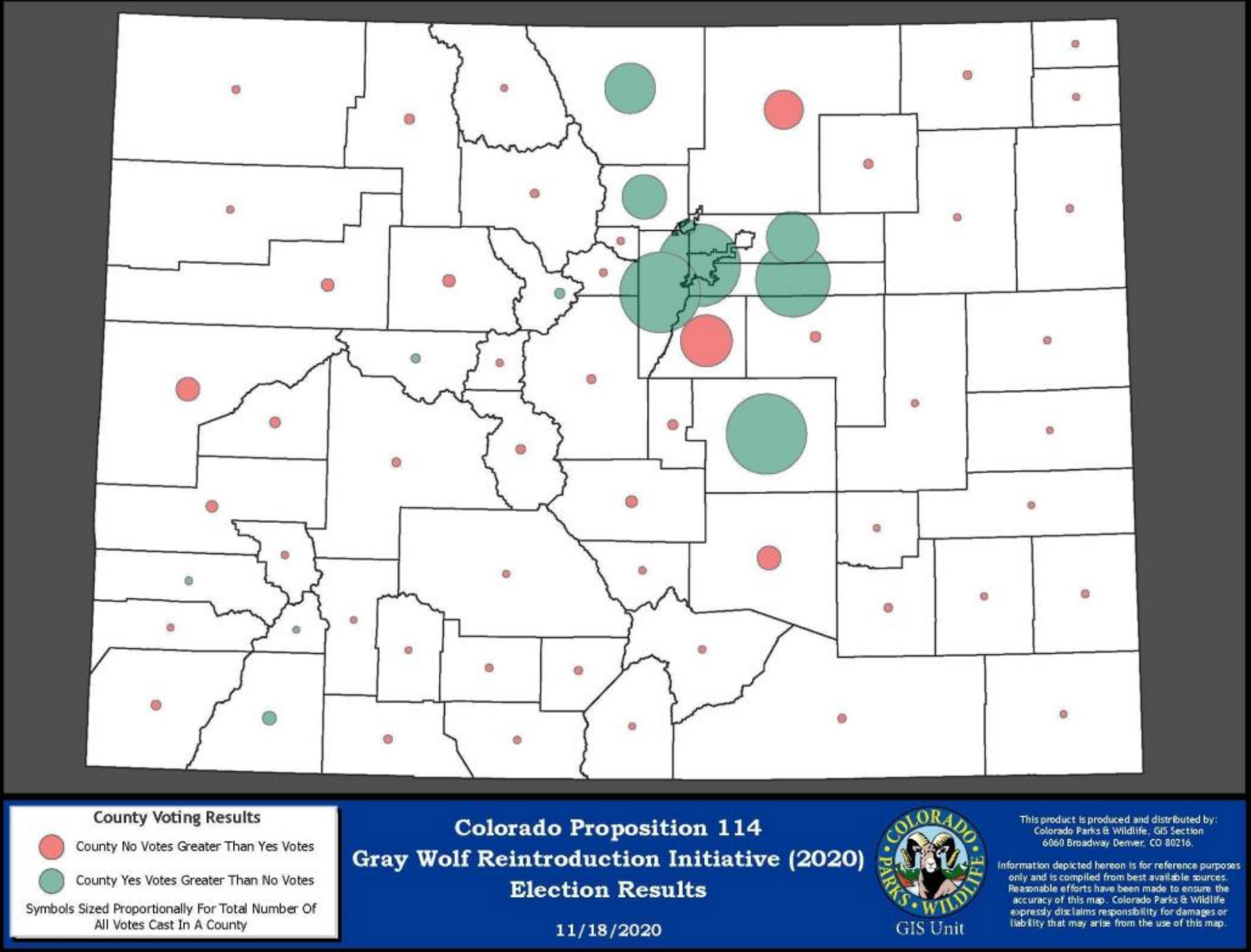

Proposition 114, now state statute 33-2-105.8, passed by a relatively meager 56,986 votes (just 1.8%) in the November 2020 election — it only needed a simple majority to pass. Most votes came from Colorado’s Front Range urban corridor, including Denver, Douglas, El Paso, Jefferson, Arapahoe, Boulder, Adams, and Larimer counties.

These eight counties provided 1,260,782 of the 1,590,299 votes favoring wolf reintroduction on the state’s Western Slope. Located west of the Continental Divide, the Western Slope includes areas along the I70 corridor between Glenwood Springs and Vail.

Glenwood Springs is more than 150 miles west of Denver.

In other words, the “yes” votes were overwhelmingly cast by Coloradans who won’t have to live with wolves. At least not anytime soon.

GOOD GEAR – Explore All Things Unknown With the BRCC Beyond Black Roast

The Divide Over Wolves in Colorado Runs Deep

The stark divide between the ranchers who will have to live with new wolves on the landscape and pro-wolf advocates was evident in the public input sessions.

CPW has received 3,800 written public comments, and more than 250 people have put in their two cents at live and online public comment sessions since January. The fifth and final meeting occurred on Feb. 22.

One of the more controversial points of the Colorado wolf reintroduction plan is lethal control.

Wolves in Colorado are currently listed as a state endangered species, and killing one can potentially carry some stiff penalties, including a $100,000 fine, jail time, and loss of hunting privileges.

Ranchers want the right to defend their livestock from predatory wolves, but wildlife advocates want to nix the part of the plan draft that makes concessions for ranchers to kill wolves threatening their cattle, sheep, horses, and dogs.

Don Gittleson, a cattle rancher near Walden, Colorado, has been dealing with wolves naturally spreading south from Wyoming and harassing his livestock. During the CPW public comment period, Gittleson told officials about the long sleepless nights he and his sons spent in uncomfortable pickup trucks parked in pastures in vain attempts to protect his herd from prowling wolves.

“I need to know there’s a way to deal with problem wolves so I can sleep at night.”

— Janie Van Winkle, Fourth-Generation Rancher

“They were getting pretty brave the last time they came in the pasture when I was there,” Gittleson said. “They attacked a cow and a calf. I had the lights on, and I was about 400 yards away from them. I started the truck back up and drove right at them with the horn honking because I was afraid they’d kill that calf before I got there.

“They were still there fighting with that cow when I got there. I ran two of the pups off. But as soon as I saw the male, I quit chasing them, and I chased him the length of the field.”

“I implore you to follow the SAG (Stakeholders Advisory Group) recommendations regarding lethal control,” Janie Van Winkle, a fourth-generation rancher from Western Colorado, told the commission.

“I need to know there’s a way to deal with problem wolves so I can sleep at night. If there are no problems, it won’t matter, but I need to know I have tools available that work. Our counterparts in the northern states tell us this is a critical tool in the toolbox,” she added. “All the other conflict minimization feels good but works only for a short time.”

Despite the pleas of Colorado ranchers, pro-wolf advocates believe nonlethal methods of dealing with problem wolves should be enough.

“We have a 16-year demonstration study of the nonlethal tools and methods that have been used to protect 20,000 sheep across a pretty rugged terrain, much like most of Colorado, at least a good part of it,” said Suzanne Aha Stone, executive director of the International Wildlife Coexistence Network.

RELATED — Watch: Grizzly Bear Versus Wolves

Wolf Hunting in Colorado?

The proposed plan also leaves hunting on the table as a potential management tool if Colorado’s wolf population booms. Although many commenters fought to remove the option from the plan, the commission decided to keep the option to reclassify wolves as a game species in Phase 4 of the plan.

The details of reclassification remain vague, however, because “forecasting the details of this future is impossible using currently available information.”

Reclassification as a game species could allow wolf hunting as a management tool across the state.

Wildlife commissioners will approve a final plan for wolves in Colorado at a meeting scheduled for May 3 in Glenwood Springs.

READ NEXT — The Current Status of Gray Wolves and Hunting in the U.S.

Comments