Before the advent of firearms, humans used far simpler tools to kill game in the earliest era of hunting history. Implements progressed from knives, spears, and other primitive weapons made from stone, then bronze, then iron as the centuries progressed. On this continent, Native Americans used stone knives, speartips, and arrowheads right until firearms from the Old World became widely available and more affordable in the 1600s.

Along the way, projectile hunting tools were developed that usually doubled as weapons of war, like the bow, the atlatl, and the sling — but that was where technology stayed for thousands of years before firearms came on the scene. In North America, people hunted animals on foot without even the advantage of horses until the early 1500s. Effective range was limited and often required hunters to get very close to extremely dangerous animals, risking being trampled by a bison, gored by a boar, or mauled by a grizzly. Often it took a group of coordinated hunters to bring down one animal.

Related: How To Start a Gun Dog

Matchlock Firearms

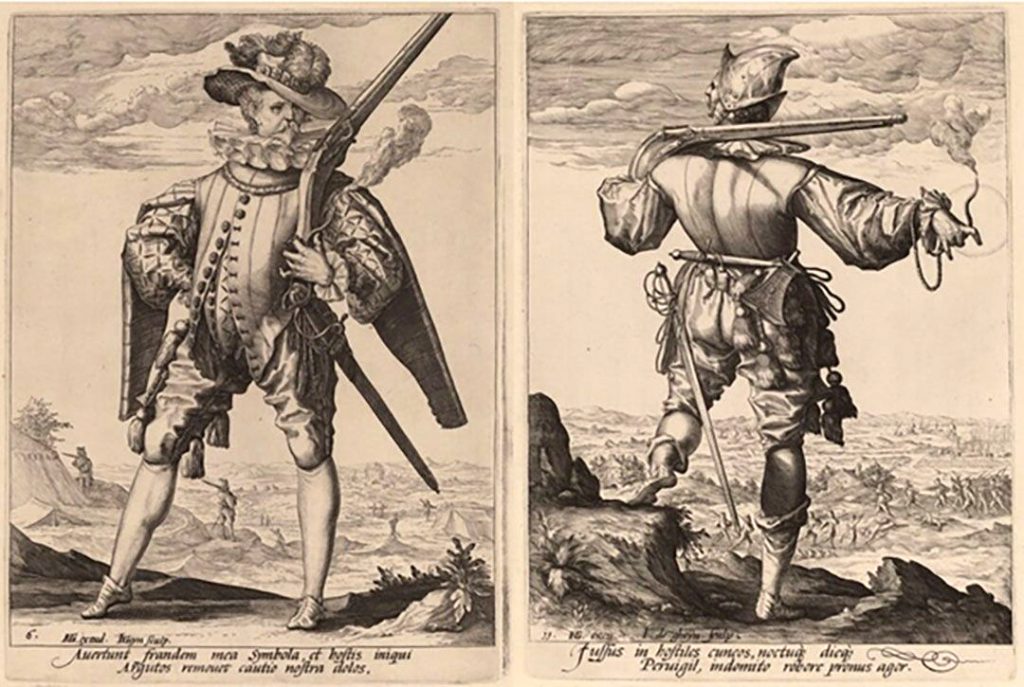

In the Old World, handheld firearms had just become a viable technology when the first European settlers arrived on the shores of what would become America in the early 1500s. The guns they brought with them were matchlock muskets, which had begun to appear in the late 1400s. These were single-shot muzzleloading firearms with an aesthetic that was more artistic than ergonomic. They were also quite heavy, often requiring shooters to steady the gun on a shooting stick, or an unfortunate assistant gunner’s shoulder, before making a shot.

The ignition system on these firearms was complicated and finicky. A slowly burning match cord, sort of like a fuse, was lit on one end and clamped in a set of metal jaws attached to a moving arm. Pulling the trigger moved the arm and lowered the burning cord into the flash pan. The powder in the pan was ignited, and in turn ignited the main powder charge in the chamber to fire the musket.

While it was certainly an improvement in knockdown power over a bow and arrow and took less skill to master, but it was far from perfect and was very slow to load and make ready.

The ever-present glowing match and a small amount of smoke it gave off could give away your position, and firing the gun in any kind of inclement weather was essentially out of the question. Still, it was state-of-the-art for the time.

Imagine stalking game while holding a giant hunk of poorly shaped wood and metal with a burning rope clamped to it, and then try to imagine loading such a contraption in the woods in even a slight misting rain. It was far from ideal, but all technology must begin somewhere.

A hunter’s matchlock kit would have included an extra length of match, powder, and shot or lead balls, and possibly a Y-shaped shooting stick to help support the heavy barrel. If the match stopped burning, the only way to fire it up again was to build a fire with steel and flint to relight it. The first lighters wouldn’t come along until 1823 and stick matches didn’t hit the scene until 1826.

Related: Gun Maintanence: Keep Your Firearm Running Smoothly

Wheel-lock Firearms

The next advancement in firearm tech was the wheel-lock. It was first used in the 1520s but took quite a while for these guns to make it across the Atlantic. When they did, the matchlock became functionally obsolete.

The wheel-lock mechanism was an exceptionally complicated ignition system, even by today’s standards, and especially compared to the matchlock. The central component of the lock — the wheel — was a piece of hardened steel. To make the gun ready to fire, a spanner wrench was attached to the wheel and it was wound up tightly under tension. A piece of pyrite was placed in the cock (a clamp on the end of a metal arm). When the trigger was pulled, the spring tension was released and the wheel would spin. The spinning steel of the wheel made contact with the pyrite and produced sparks, which ignited the powder in the pan — hopefully.

The wheel lock was a huge improvement over the matchlock, eliminating the burning cord and making the gun a bit more moisture proof and safer to use. A hunter no longer needed to carry a burning match, but fine powder for the pan and coarser powder for the main charge was still needed, as well as separate shot or lead ball projectiles, and, of course, the spanner wrench. A ramrod was also necessary for loading, as it is with any muzzleloader.

Unfortunately, the very essence of the wheel lock was its undoing. Because of the complicated mechanism, they could only be made by skilled craftsmen who could fabricate and assemble all the small parts, and of course, everything had to be made and fitted 100% by hand. When something went wrong and repairs were needed, only a craftsman with a specific skillset could make them or create replacement parts. The need for a spanner wrench to wind the wheel was also an issue. If a hunter dropped their wrench in the field, the gun became nothing more than an awkward club.

Related: The Many Guns of John Wayne on the Big Screen

Flintlock Firearms

“Flintlock” has become a catch-all term for a couple of different types of ignition systems that have been lumped in with the true flintlock, namely the miquelet and snaphaunce. For our purposes, though, we’ll consider them all flintlocks, since they all use flint.

When the flintlock was designed in the mid-16th century, the basic principal of the wheel-lock was maintained, but the uber complicated ignition mechanism was jettisoned for something much more robust and simple.

Powder and ball still had to be loaded from the muzzle, but there was no need for a spanner wrench. Instead, a piece of shaped flint was clamped in the jaws of what a modern shooter would consider a hammer, but was called a cock at the time. The cock was pulled back until it locked in place under spring tension. When the trigger was pulled, the cock was released and swung forward, allowing the flint to scrape against a piece of steel called a frizzen. This created sparks that rained down into the gunpowder in the pan, which then ignited the main charge. The frizzen also kept the powder in the pan in place and covered while carrying the gun.

Unfortunately, not every strike caused an adequate spark, and sometimes a shooter would have to recock and try again. And sometimes the sparks would ignite the powder in the pan, but the main charge wouldn’t ignite and the gun wouldn’t fire, which is where we get the phrase “flash in the pan.”

Generally speaking, guns became more manageable in size and ergonomic in design during the flintlock era of firearm hunting history. Size and weight were gradually reduced, but their smoothbore barrels were still quite long to achieve a measure of accuracy and range with round lead ball projectiles.

Around this time, the far more practical flintlock muskets were designed to be less artistic and more suited for the field, for hunting, and for battle. Thanks to the smoothbore barrels, flintlock muskets could also be loaded with shot pellets to hunt a variety of game.

These were working guns; even the finest “Kentucky rifles” as we know them today saw use in the field. A hunter’s kit would have included powder for the main charge and the pan, cotton cloth patches or wadding material, projectiles, a ramrod, and spare fints.

The flintlock remained the pinnacle of firearm technology up until the early 1800s and through the invention of rifled muskets, but it was far from perfect. Flintlocks were more resistant to weather and moisture than previous designs, but they were still muzzleloaders that also required a measured main charge of gunpowder, plus finer gunpowder for the pan. Water was the enemy, flints could break or shatter, and they were slow to reload. When rifled barrels came along, the accuracy of flintlocks increased dramatically, but the bores were tighter and therefore they were more difficult to load. After building up black powder fouling from two or three shots, they were nearly impossible to load without cleaning.

Then, a Scottish clergyman came along and changed the course of firearm hunting history forever.

Related: Starter Kit: Learn the Shotgun Sports Like Olympic Trap, Skeet, and Sporting Clays

Percussion Hunting Firearms

As the story goes, Rev. Alexander John Forsyth conceived the concept of percussion ignition one day while out duck hunting with his flintlock fowler and became frustrated with his gun’s lock time, which is the amount of time it takes for the gun to actually fire after the trigger is pulled. The delay was long enough after the sound of the mechanism firing and the pan igniting that a hunter’s quarry could have time to move before the projectile reached them.

Dismayed by the gun’s performance, he figured there had to be a better way — and he was right. The experience inspired him to begin experimenting with fulminate of mercury (yep, the same stuff Walter White used in Tucco’s drug den on Breaking Bad).

His scent-bottle lock was patented in 1807. It used a small container of fulminate of mercury and every time the hammer was cocked, a bit of the chemical was dispensed. When the hammer impacted it, the chemical would ignite, and quickly ignite the main charge. The design eliminated the need for a flash pan, but the “percussion cap” was still a ways off.

The most important advancement to the percussion system was the creation of the copper percussion cap, which was patented in the United States in 1822 to avoid any legal challenges from Forsyth in Europe. It wasn’t long before the percussion ignition system would come to dominate firearms worldwide.

The self-contained percussion cap completely illuminated the need for a separate loose powder charge in the lock mechanism, and the “flash in the pan” was now a fleeting thing of the past. A hunter’s loadout for his firearm was reduced to some kind of pouch filled with percussion caps, powder for the main charge, and projectiles. And best off all, the caps were extremely water resistant.

With a heyday much shorter than that of the flintlock, percussion cap rifles saw considerable use until the advent of self-contained metallic cartridges in the 19th century. Even after early metallic cartridges were widely available, many hunters still continued to carry and use their percussion firearms.

Related: The Best Shotgun Moments in Western Movies

Advent of Self-Contained Metallic Cartridges

Finally, we come to the grandaddy of what hunters still take into the field today.

By the 1870s, self-contained metallic cartridges set the future of firearm hunting history. These are exactly what they sound like. Everything needed to shoot the gun was all wrapped up in one neat package. A casing of copper, and later brass, was fitted with a percussion cap at the rear (a primer), filled with the main charge of gunpowder, and topped with a projectile (bullet).

While plenty of companies developed cartridge hunting guns in the late 19th century, Winchester cemented their place in history with designs from John Moses Browning, including the Models 1873, 1876, 1886, 1892, 1894, and 1895. A hunter now only had to haul their firearm and ammunition into the field, and while metallic cartridges, then and now, aren’t completely waterproof, they are a damn sight better than anything that came before it in terms of weather resistance, ease of use, and reliable functionality.

They also made possible various repeating firearms, like the Winchester models, and by the early 1900s, the fire semi-automatic firearms.

Countless hunters have filled millions of tags with those gun models alone, and that doesn’t even scratch the surface with bolt-action and semi-automatic rifles from companies like Savage, Remington, Mossberg, Weatherby, and more.

Today, with a dizzying variety of standard production and wildcat cartridges on the market – not to mention custom hand loads — the potential of modern centerfire cartridges seems to be limitless.

Read Next: The Maxims: The Father and Son Who Invented the Machine Gun and the Suppressor

Comments