The Tennessee Fish and Wildlife Commission recently took significant steps to reverse the downward trending turkey population in the state. In a decision that seems in step with national conservation momentum, the 2023 Tennessee turkey season will see changes made to dates, bag limits, and permitted hunting methods.

At a June 3 meeting, the commission decided to delay the season opener by two weeks, reduce the turkey bag limit from three birds to two, increase the bag limits on certain predator species, and ban reaping or fanning on all public hunting land.

“I would say the overall health of the [national] turkey population is in decline.”

—Mark Hatfield, NWTF

Roger Shields, a biologist with the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency, told Free Range American that while bird recruitment has been in decline for the past 20 years, the past few years have yielded lower numbers than they would have liked.

“We constantly hear reports from our hunters, from our landowners, even our staff, that they just don’t see the number of birds that they used to see,” Shields said. “I think that was really the thing that was driving a lot of [these changes]: a concern for the fact that people aren’t seeing the flock sizes that they had in the past, and what we can do to kind of bolster that.”

Harvest data has been the primary source of understanding the health of turkey populations in Tennessee, but Shields said more accurate and thorough estimation processes are now being employed.

“This spring will be our third year of conducting a post-season harvest survey,” he said. “We are capturing information on hunter participation and hunter effort — how many days they’re spending in the field. Also, our staff have always done a brood survey: a wild turkey summer survey.”

“There are counties where we never get any observations from staff because we just don’t have very many staff in those areas,” he said. “So, we’re going to open that up to the general public and try to get their involvement so we can get better numbers of productivity in all parts of the state.”

RELATED – The Sounds of the North American Wild Turkey

Tennessee Turkey Season Changes

Delaying the season opener was an obvious first step in improving the recruitment of poults. Currently, the opener falls right at the high point of nesting. The season will now open on April 15 with the youth opener scheduled for April 8.

State wildlife officials and biologists believe that the additional time will allow for a greater chance of poult survival. Likewise, keeping mature, breeding toms in the mix a little longer also helps improve hen productivity.

Additionally, a reduction in the bag limit from three birds to two and allowing only one jake to be killed per season should help increase the number of younger birds that become mature birds.

All these moves should result in more turkeys in the field.

Of course, more poults in nests also mean more targets for predators like raccoons, opossums, and bobcats. Because of this, the commission voted to extend raccoon and opossum hunting season to March 15 and to double the bag limit.

The commission also approved bobcat hunting during the statewide deer archery, muzzleloader, and gun seasons.

Lastly, the commission voted to ban reaping or fanning for turkeys on all public hunting land — a stalking method employed by hunters who hide behind a fanning decoy or turkey fan and move to get within shooting range of a turkey. It’s highly effective but controversial method from a hunter safety perspective and, for some, ethically.

Tennessee joins six other states that have adopted the same position. Alabama, Michigan, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island have statewide reaping bans in place, while South Carolina bans reaping on public land only.

Sixteen other states have a statement of caution against stalking in their turkey hunting regs or include species-specific guidelines based on safety concerns.

RELATED – Hunting the Mountain-Dwelling Merriam Turkey

The State of the Gobbler Nation

At the national level, determining the health of the US turkey population isn’t as cut-and-dried as looking at increases and decreases from year to year.

As Mark Hatfield, national director of conservation services for the National Wild Turkey Federation (NWTF) told FRA, there are several factors that determine a population’s health, and that sometimes, a growing population isn’t necessarily a healthy one.

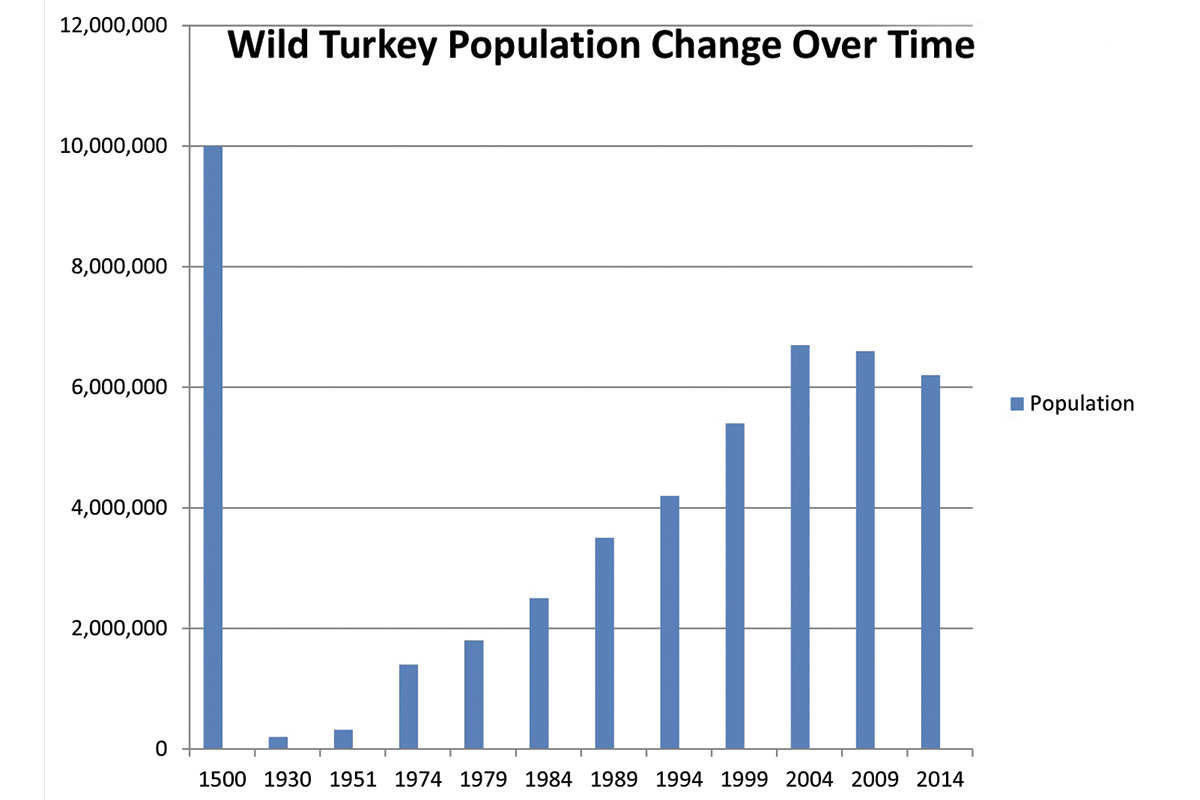

“I would say the overall health of the [national] turkey population is in decline,” Hatfield reported. “We’ve seen a decline in turkey populations since the mid-2000s. But in the past five years, give or take, we’ve seen populations stabilize in some places. About a third of the country is stable, a third is probably decreasing in population, and a third is probably increasing.”

“But over-abundance issues are not healthy,” he added. “Low reproduction is not healthy. There may be some areas that even though they’re stable, there may have been room for them to grow.”

At the end of the day, it really comes down to how the birds are managed on state and regional levels, and there is no one-size-fits-all management solution.

Even though the estimated number of birds nationwide has shrunk to 6 million from 2004’s high-water mark of 7 million, Hatfield says, “We still have a lot of turkey on the landscape.”

RELATED – Modern Turkey Loads: Worth the Money, Maybe

Variables and Tough Questions

When it comes to the health of a turkey population or successful recruitment, there are countless variables that need to be in favor of the birds for them to thrive.

According to Hatfield, changing climate, degradation of brooding and nesting habitat, development, predators, and even the length of time since restoration efforts have been completed all play into the productivity of any given flock.

“If you’re at two poults per hen, you’re stable. Above two poults per, on average, you’re starting to increase,” he said. “If you’re below two, you’re declining. So that replacement or that recruitment is critical. We just have to make more birds.”

Changes in hunting regulations like those being made in Tennessee can lower some barriers to recruitment.

Aside from universally agreed-upon moves like delaying season openers and decreasing bag limits, when rules start to encroach on hunters’ methods for killing a bird, hackles are going to be raised.

Controversy over certain turkey hunting tactics is nothing new. Federal’s introduction of the Tungsten Super Shot (TSS) turkey load in 2018 and the ensuing ethical duels between tungsten and lead shooters everywhere is proof of that. Because of the high density of TSS pellets, they pattern tighter at greater distances, meaning they allowed hunters to take farther shots on turkeys than ever before and more accurate shots on birds inside 40 yards.

Hatfield pointed to such advancements in shotshell technology as an example of the learning curve.

“We need to make sure that we don’t make broad assumptions that everybody’s utilizing this new shotshell technology,” he said. “Recent studies have shown that people still feel that their most effective range is 40 yards and below. Regardless of shooting lead or TSS, they still feel their effective range is 40 yards or below.”

Regarding fanning or reaping, Hatfield said that there is simply not enough data available right now for NWTF to take a definitive position on the hunting method.

“As an organization, we recognize that we need to invest more to find that data to make sure we are information-driven in our decision,” Hatfield said. “In the meantime, state agencies have the responsibility to manage wild turkeys, and when there is a lack of information, many times — and correctly — the state agencies are taking a conservative approach to ensure that the population remains healthy.”

“I don’t think that all turkey hunters are using [the reaping tactic],” he added. “I think it’s a segment but we don’t understand what that segment is and how that impacts the efficacy of the method.”

Hatfield understands the immense task of collecting that data is not an easy undertaking — but it can be done, and done well, as Mississippi has shown with its Turkey Report.

“How do we create a robust survey with enough rigor that we can look at regional applications of new techniques?” he said. “It’s just not tied to fanning and reaping. It’s the advancements of the appearance of decoys. It’s shotshell technologies. It’s all of these other things that compound the harvest per unit effort.”

While no single natural variable or human-made hunting tactic will be the silver bullet, the answer to one big question might drive a lot more change in turkey regs across the country.

“Are we creating a more efficient turkey hunter with this technology?” Hatfield asked. “If so, there may be trade-offs. And if there are trade-offs, we may need to make adjustments like Tennessee Wildlife Resources did to ensure turkey populations remain healthy and maximize opportunities.”

READ NEXT – U.S. Turkey Super Slam: How a Hunter Bagged Mature Toms in 49 States

Comments