When I first started coyote calling some 15 years ago, my go-to was the Superjack distress call on my Johnny Stewart electronic caller, and it was money. I’d turn it on — softly at first — then boost the volume for a few minutes. Then, I’d hit the mute button and wait a minute or three before letting the call start screaming again. I didn’t keep a predator journal back then, but it seemed like every other stand produced a dog.

Then, things got hard. The two-track roads that sliced across the cedar-dappled plains near my Colorado home started getting more traffic. It was frustrating. For a while, I had area song dogs and bobcats to myself, and then, seemingly overnight, everyone was calling predators. I got really nervous when I started seeing vehicles with out-of-state tags.

The Game Changed

I’m a slow learner, but after a dozen stands in some of the best spots I knew without a single dog to show for it, I got the message. The conditions were perfect; sign was everywhere — and nothing. I heard coyotes howl and, on one occasion, glassed a lone dog sunning in the middle of a cattle pasture. When I turned on the Superjack, he tucked tail and ran.

I want to tell you I figured it out all on my own, but I’m not that smart. One frosty January afternoon, I hit the prairie with my good buddy Jason Weaver. Jason is a coyote caller too — much better than me — and when he hit the play button on his FoxPro, I was surprised.

I wasn’t sure of the sound, but what I was sure of was 3 minutes and 45 seconds into the stand, a pair of coyotes emerged from a heavy sage draw and came at full tilt. We killed both those dogs, and while we were gathering our gear, I asked Jason about the sound, and I’ll never forget what he said:

“Oh, that was a pronghorn-fawn-in-distress sound. Take a look over there on the horizon. There’s a group of pronghorn just under that patch of cedars down in that cactus flat. I started calling more coyotes when I started matching my sounds to the prey in the area. The days of using a rabbit-distress every time are over, my friend.”

On our next stand, we put our backs to a stock tank set smack in the middle of an ocean of golden prairie grass. The grass was full of meadowlarks, and numerous other bird species lined the pasture fences. I can’t tell you what exact bird distress sound Jason went with, but before he turned on the caller, he told me that while we were walking in he saw two piles of crap with yellow feathers in them — feathers that looked to him like meadowlark feathers.

A male coyote ran the caller over less than five minutes into that calling sequence. I disposed of him with a 12-gauge as he tried to make his exit.

RELATED – ‘Alarming’ Wolf Hunting Tallies Near Yellowstone Not Alarming at All

I Saw the Light

That afternoon spent on the prairie with my good buddy changed my predator calling approach. I started using only distress sounds that matched the prey in my area. One could even say I went a tad overboard.

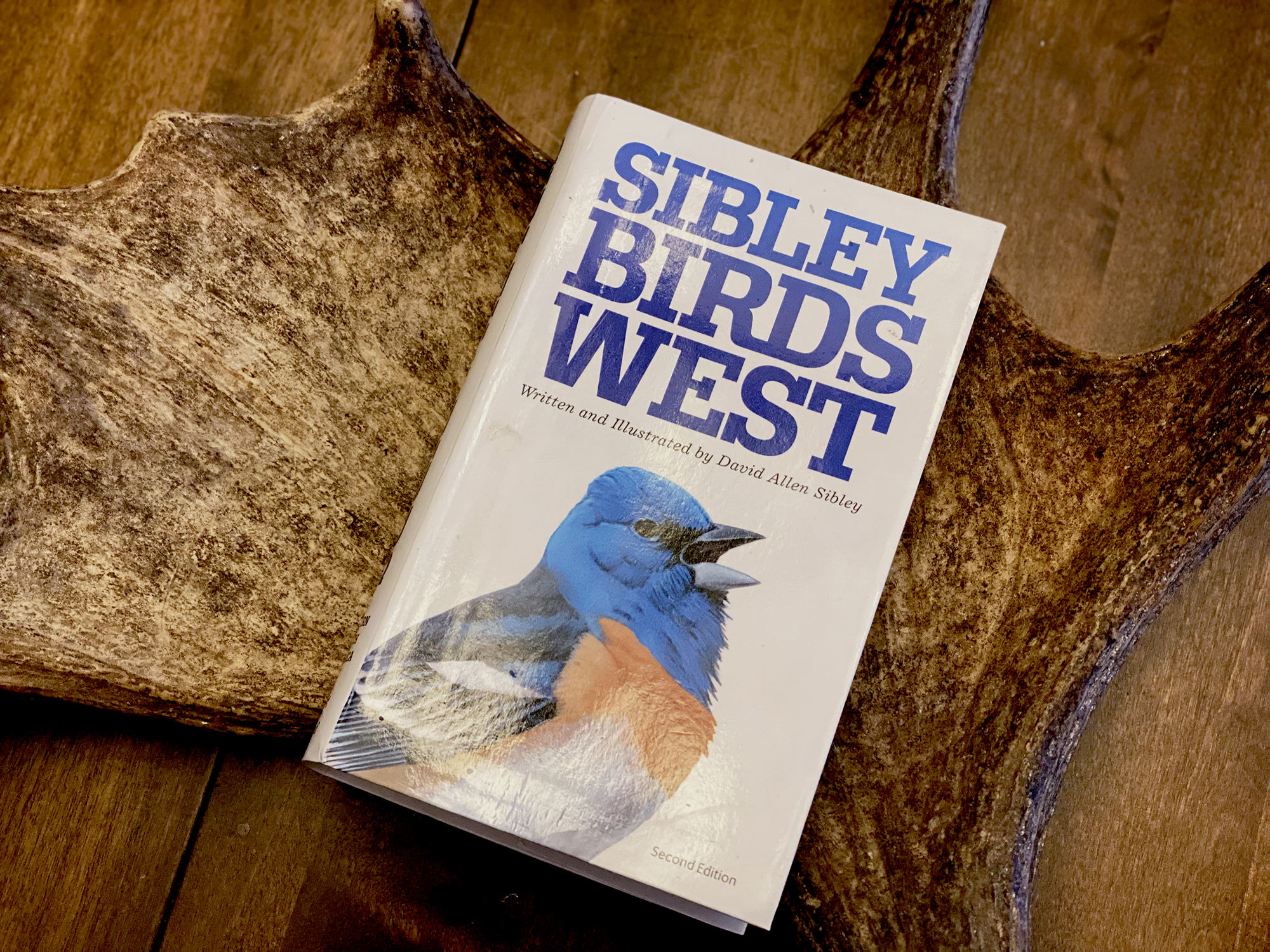

Bird distress sounds quickly became some of my favorites, and I purchased a copy of The Sibley Field Guide to Birds of Western North America to better identify species. After making a positive ID, I would visit FoxPro and other sound libraries to see if I could find the exact distress sound of the identified bird.

You’d be surprised what sounds are out there in cyberspace. I’ve found everything from a robin to a blue jay to a scissor-tailed flycatcher. Oh, and I started killing a lot more coyotes. I also discovered bobcats also like bird sounds, especially when played lightly in riparian habitats. Just something to keep in mind.

The pieces of the puzzle all started to come together. I used bird sounds combined with whitetail fawn distress and turkey distress sounds when calling river and creek bottoms. If you can locate a prairie dog town on the plains, play the wind right, and make a stand with the right distress sound, I can almost guarantee you a coyote if the area hasn’t been overrun with hunters. You get the idea.

RELATED – 6 Simple Steps for Duck Hunting Creeks: Guns, Gear, and Tactics

Dig Into Sound Libraries

Savvy electronic game-call makers like FoxPro, Lucky Duck, MOJO, Icotec, and others all offer great products, but they also have incredible sound libraries. Don’t sell yourself short and stick with the meager 50 or 100 sounds that come already downloaded into your call’s remote. Visit the manufacturer’s online sound libraries. Furthermore, don’t settle for a single, say, pronghorn distress sound if there’s more than one available; if the library has two or three different pronghorn distress sounds, download them all and any others you think might be useful to you.

Two distress sounds from the same animal may sound similar to your ear, but just like switching from a silver-bladed Panther Martin spinning lure to a gold-bladed model, a slight difference in tone or pitch can be the difference between a successful stand and striking out.

RELATED – These New Year’s Resolutions Will Make You a Better Hunter

Don’t Forget About Trail Cams

Don’t overlook the importance of trail cameras and their role in helping you identify what sounds to use in a given area. I document every predator picture I get on my cameras when those cameras are set out for deer and other game. Why? Not only do the cameras tell me where predators like to be and when, but often, I get photos of predators with prey in their mouths, which tells me even more.

Last season I got two different pics of coyotes, and both had deer legs in their mouths. In December of last year, on a bit of dirt where I like to call, I got a picture of a beautiful bobcat with a rabbit clamped in its jaws. I know what sound I will be using there in a few weeks when the temperatures drop, and I head in after that kitty.

READ NEXT – Coyote Hunting: Intense Scouting and Planning Pay Off

Comments