Watching a skilled precision shooter get down to business is a real treat. Repeatedly hitting 10-inch targets from 400 yards in standing and kneeling positions doesn’t seem like it should be possible, but it’s actually a common tiebreaker at Precision Rifle Series (PRS) matches, and the pros make it look like a walk in the park.

According to the Marine Corps, I am a rifle and pistol “expert” — whatever that means. How curious, then, that there are days when I swear I’d miss the muzzle if it weren’t attached.

It sucks to suck, so I jumped at the opportunity to attend Vortex Edge for long-range precision rifle training. For three days, I got to surround myself with long-range shooters from civilian, military, and law enforcement backgrounds and learn from some of the best instructors in the business.

Their professional instruction took me from zeroing my scope to making my own wind calls and engaging targets out to 1,000 yards with more precision than I could have dared to hope for.

Far be it from me to try to convey all the knowledge they imparted here, but there are a few key takeaways from the course that will benefit anyone interested in taking up the sport. Long-range precision shooting is by no means easy, but it might be simpler than you think. Focus on these six basic concepts, and you’ll be on the right track.

Precision Rifle Series: Master the Fundamentals

I don’t care if you’ve been shooting for five minutes or five decades, and it doesn’t matter if you want to improve your skill with a pistol, rifle, carbine, or shotgun. The fundamentals never stop being relevant, and they will make or break your success.

- Body position

- Sight alignment and sight picture

- Breathing

- Trigger control

- Follow-through

Use your bones, not your muscles, to create a natural point of aim. Establish proper sight alignment/sight picture free of scope shadow, blurriness, and parallax. Remember to breathe naturally and fire during your natural respiratory pause.

Use a slow, steady trigger press — don’t try to time your shots with a wobbly point of aim. When the shot breaks, manage recoil to stay on target and spot your impact so you can make the necessary adjustments on follow-up shots.

RELATED – The Bolt Action Rifle: A Massive and Enduring Leap for Gun Tech

Get the Right Gear for Precision Rifle Series

The farther you get from your target, the more your gear selection matters. You can get into the weeds with all the gear I used to get started in long-range shooting, but there are a few basics that will put you on the right path.

If you’re new to precision shooting, it’s unlikely that anything in your gun safe will get the job done without significant modifications. The thin, lightweight barrels on standard hunting rifles are susceptible to overheating, even if the manufacturer declares them capable of sub-MOA accuracy. Most bolt action rifle stocks don’t allow for custom-fitting. The same goes for your scope. Plain crosshair reticles and BDC reticles that are perfectly good for hunting applications aren’t precise enough to go the distance.

At the same time, some newcomers to long-range precision shooting go overboard. One of the most common mistakes the instructors at Vortex Edge see is students showing up with too much gun and — believe it or not — too much scope.

Beastly loads like .338 Lapua have their place in precision shooting, but you’re not going to learn very much if you start wincing from the cartridge’s punishing recoil halfway through a day of training.

Likewise, students have a tendency to crank their variable-power scopes up to the maximum magnification setting and leave them there. I did the same thing at first, but I ended up doing my best shooting at 16- or 20-power magnification, not 25.

And when you’re shooting out to 1,000 yards and beyond, you have to get used to twisting the magnification ring on your scope a lot. Part of the game is scanning for targets at lower magnification and then zooming in on them. It’s easy to get lost in your scope on an open shooting range at 20–25X.

What you really need to get started, as I recently learned from experience, is a purpose-built precision rifle with a reliable action, a crisp trigger, a thick free-floating barrel, and a stock or chassis that’s adjustable for length of pull and comb height. A Savage 110 Precision or a Ruger Precision Rifle in 6.5 Creedmoor would be a fantastic entry-level option. And I do mean entry level.

PRS vets would look at these guns on a firing line and laugh in your face as they take a linen rag to their $20,000 rig. But the truth is, both are solid factory precision rifles that will help you learn what you want out of your long-term long-range rifle when you’re ready to dive in all the way.

Then there’s the optic, where you can really sink some cash. Your scope should have variable power somewhere in the ballpark of 5–25X, exposed and locking turrets, parallax adjustment, and a technical reticle with subtensions in milliradians or minutes of angle.

Both MRAD and MOA are effective units of angular measure (kind of like using miles or kilometers). Most scopes feature turret adjustments in 0.1 MRAD or 0.25 MOA. With those increments, one click of your turret will move your 100-yard point of impact 0.36 inch with an MRAD scope or 0.25 inch with an MOA scope.

When it comes down to it, it doesn’t really matter which you choose. The important thing is to keep all your data, turret adjustments, and reticle holds consistent with one or the other. The firing line is not a good place to bust out a calculator and convert units. That said, these days, more shooters tend to go with MOA.

I kicked off my long-range shooting journey with a Vortex Strike Eagle 5–25×56 FFP on top of a Savage 110 Precision and had great results.

Great Long-Range Beginner Setup:

Rifles: Savage 110 Precision, Ruger Precision Rifle

Scope: Vortex Strike Eagle 5–25×56 FFP

Chamberings: 6mm Creedmoor, 6.5 Creedmoor, 6.5 PRC, .300 PRC

RELATED – The Bullpup Doesn’t Deserve to Be in the Dog House

Seek Professional Long-Range Instruction

If you have quality gear, you can almost guarantee that the weak point will be the person pulling the trigger — in other words, you. Once you make the kind of investment it takes to get into long-range precision shooting, even at entry-level, you owe it to yourself to seek professional instruction. Before you get started, look for training opportunities in your area and budget a course or two into your plan.

As with any shooting discipline, receiving quality instruction early on is crucial to success.

One of the most important lessons I took from the Vortex Edge Long Range Pipeline is the overwhelming importance of fundamentals. Things such as building a stable shooting position, acquiring a clear sight picture, managing breathing, executing a proper trigger press, and staying on target with good follow-through never stop being relevant. In fact, the farther out you shoot, the more magnified the hitches in your fundamentals become.

The instructors I worked with aren’t just extremely accomplished shooters, they’re also excellent teachers who remember what it was like to be new to the game. A good instructor will see right through problems you’d spend months struggling to diagnose, and they’ll correct issues before you have a chance to build bad habits.

Three days of long-range training at Vortex Edge costs $750. If I spent that much money on ammunition and tried to learn on my own, I’d probably end up worse off than when I started. Instead, I learned more in three days than I did in four years of active duty in the Marine Corps. There are great instructors all over the U.S. — find some near you and learn everything you can from them.

Never Trust and Always Verify

Before I attended my long-range school, I downloaded the GeoBallistics app, plugged in a bunch of numbers from Savage and Hornady, and built out a range card from 100 to 1,000 yards. Job done, right?

One of the first things we did in the course was chronograph our rifles. None of us saw the exact number advertised on our ammunition boxes. Nobody ever has — not every time, anyway. Each rifle and each individual cartridge is unique, so deviation is inevitable.

Hornady measured its 6.5 Creedmoor 140-grain ELD Match ammunition at a muzzle velocity of 2,710 feet per second. A chronograph clocked 10 bullets from my Savage 110 Precision’s 24-inch barrel at an average of 2,631 fps, with an extreme spread of 51 fps and a standard deviation of 14.6 fps — different barrel, different environmental conditions.

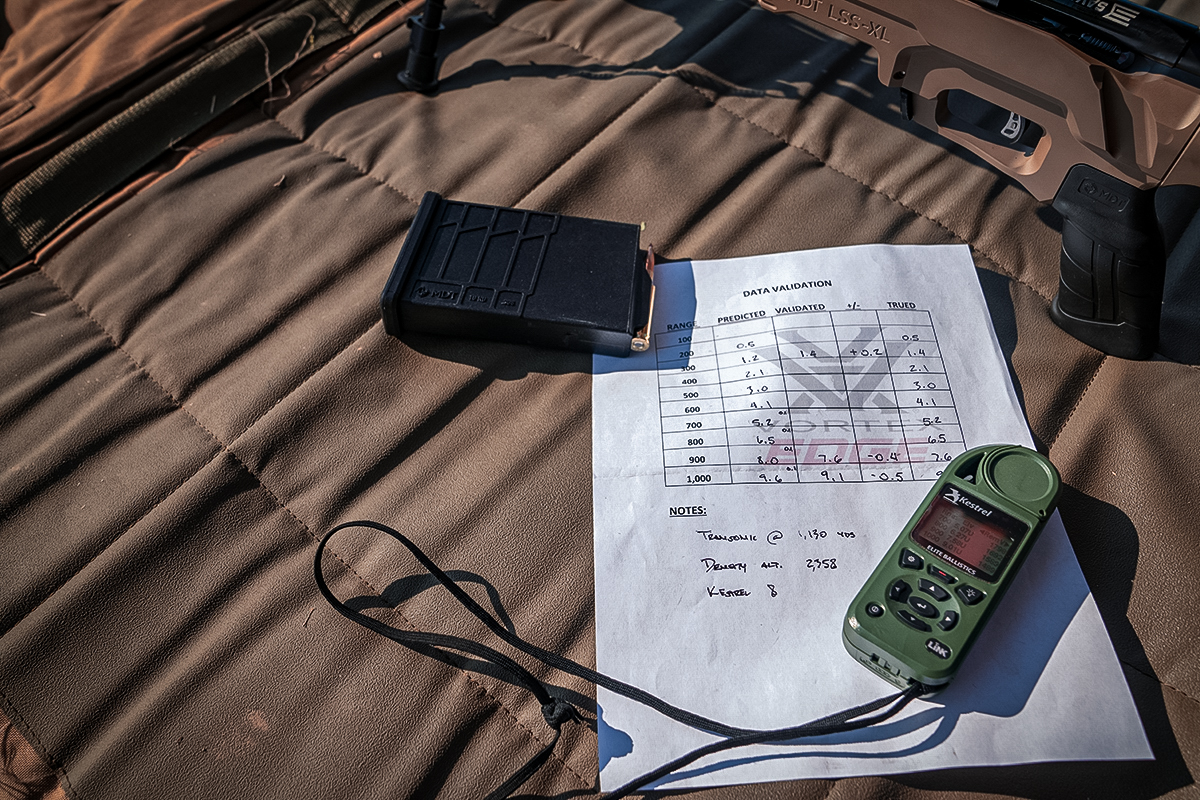

I backfilled that number into the GeoBallistics app and a Kestrel to refine my range card, then we walked targets out to 1,000 yards. Guess what? My elevation adjustments still weren’t perfect. Using the 1,000-yard target, I trued my data to come up with a range card that wasn’t theoretically correct, it was proven (as long as the density altitude doesn’t change too much, anyway).

Be meticulous about collecting and recording this kind of information. It will add up over time to become your data on previous engagements, or DOPE. The more data you have, the more likely you’ll have a record of environmental conditions that are close to what you’ll experience on a given day. Then you don’t have to reinvent the wheel — you just have to flip to the right range card.

A Kestrel isn’t just a handy way to manipulate your data on a table — it’s an essential piece of gear when it comes to making accurate wind calls and accounting for weather conditions. Long story short: If you don’t have one, you’re probably going to miss, and you shouldn’t expect to be competitive.

You can’t trust your eyes, either. At one point, I perceived three targets in a nice little line from left to right — all the same size and shape. What I couldn’t discern is that one was 200 yards closer than the other two. Because it was smaller and placed on a sneaky piece of terrain, it tricked my eyes until I performed a calculation based on its known width in inches, its observed width on my reticle, and a constant factor.

(size of target in inches x 27.77) / size of target in milliradian = yards to target

(size of target in inches x 95.5) / size of target in MOA = yards to target

I used this method with mixed results. Remember that the formula is only as good as the measurements you feed it. While I understand the subtensions in my reticle, my measurements were off enough in some cases to cause a miss. Practice this method, but get a rangefinder that’s capable of ranging targets at the distances you require. For long-range precision shooting, a rangefinder with an ELR (extended laser range) mode will boost your accuracy.

Bottom line: Rigorously collect data and trust nothing else — not your eyes, not some spreadsheet from the internet, and not the shooter next to you. The numbers on the box are a good place to start but only rely on hard data you’ve proven yourself. That Hornady ammunition paired with my rifle was golden for me — I just had to correct my assumptions of how it would interact with my barrel.

RELATED – Sharps Rifle: The Original Long-Range Hunting Gun

Wind Calls Are Everything

During the second day of training, we focused on wind estimation. We used cues such as feeling a light breeze on our skin, seeing movement in grass or mirage, or observing constant movement in the trees. These all correlate to rough guidelines for wind speed, but they’re very location-dependent — e.g., sagebrush and maple trees do not respond to wind the same way.

The instructors taught us to use a clock method to determine where the wind is coming from and to what degree it will affect a bullet in flight. It turns out that a strong crosswind is easier to account for than a shifty headwind or tailwind.

Knowing your gun speed or gun number (the speed at which a 90-degree crosswind will deflect your bullet to a specific degree) can provide a convenient starting point and make calculations easier. That assumes, of course, that you can accurately read the wind in the first place.

The pros can glance at a distant target and make a quality wind call, but the rest of us will benefit greatly from a Kestrel wind meter — hell, even the pros check their Kestrel. Once we have an accurate reading for the wind’s speed and direction, we can put our knowledge to work and calculate a precise shooting solution.

But never forget, what the wind is doing at the gun and where your Kestrel is isn’t necessarily what the wind is doing downrange at the target. That’s why it’s so important to take cues from what you see happening around your target through your scope.

I Know Why You Miss — Do You?

Long-range shooting gives us a chance to impress people with terms like spindrift, aerodynamic jump, and Coriolis effect. All those things are real, but they’re not wrenching your bullet off a brilliantly placed trajectory and robbing you of accuracy.

The instructors at Vortex Edge ran a computer simulation to isolate individual variables and determine how much each one affects hit probability.

Before you blame your rifle, scope, or cartridge selection, remember that somebody out there is shooting lights-out with your exact setup. Your gear isn’t the problem unless you picked something wildly inappropriate.

Maybe it’s shoddy ammunition. The simulation found that, given its specific parameters, improving the standard deviation of your ammunition’s muzzle velocity from 15 to 10 fps only raised the likelihood of hitting a 20-inch circle at 1,000 yards from 72% to 75%. If you master handloading and somehow manage to achieve a standard deviation of 5 fps, you’ll improve your odds to 76.5%.

Total improvement: 4.5%

What about grouping? Well, given the same parameters, improving your accuracy from 1 MOA to 0.1 MOA (which isn’t going to happen, I regret to inform you) will improve your hit probability from 70.4% to 75.4%.

Total improvement: 5%

Next, they isolated ranging. According to the model, ranging the same target within 15 yards should give you a 51% chance of success. Narrow that down to plus or minus 5 yards, and you’re looking at a 75% hit probability.

Total improvement: 24%

This brings us back to our old nemesis: wind deflection. If you make wind calls within 5 miles per hour of the real conditions, you can only expect to hit a 10-inch target from 700 yards away 48% of the time (and you can forget about shooting a grand). Improving that to plus or minus 3 mph will get you on target 72% of the time.

Total improvement: 24%

So, why do you miss? Because of marksmanship basics, the same as everybody else — judging range and wind. Buy quality match ammunition. Get your 100-yard groups inside an inch. Then, be very careful when you range your targets and get downright obsessive about making wind calls.

Simple? You bet. Easy? Hardly.

There are no cheat codes, no apps, and no technological advancements that can fix your shooting if you aren’t a devoted student of marksmanship.

The lessons you learned on day one will remain relevant for the rest of your time on Earth, and you’ll never forget that first time you ring steel at 1,000 yards using a rifle, optic, and ammo combo that you doped yourself.

You want to shoot like a pro? Get out there and start training like one. That’s the first step.

READ NEXT – The Black Powder Rifle: The Story of the First Precision Firearms

Comments