The genesis of the modern rifle lies with the humble and practically ancient black powder rifle. In the 21st century, we take for granted the basic design and function of rifles and the cartridges they fire. While advances in materials and manufacturing techniques have tweaked things here and there on both the gun and ammo sides, the heart of a rifle’s design hasn’t changed much in at least a couple of hundred years.

In the grand scheme of things, though, 200 years is just a blip. The invention of the black powder rifle, going by its most basic definition, dates back almost 1,000 years. Still, despite its worldwide historical importance, much of the origin story remains a mystery.

Before we get to all that, let’s skip way ahead and deal with the modern elephant in the room.

GOOD GEAR – Wear A Hat to the Range With the BRCC Reticle Hat

Are Black Powder Rifles Firearms?

Thanks to the crystal-clear mud pies that are American gun laws, black powder rifles (and handguns and shotguns) are not considered firearms by the federal government. They do not fall under the National Firearms Act of 1934 or the Gun Control Act of 1968.

This means they are not subject to background checks and can be shipped right to your front door (in most states). However, it doesn’t mean they aren’t subject to restrictions on the state and local levels.

With that out of the way, we’ll head back in time once again.

RELATED — Muzzleloader Hunting: How To Remove a Stuck Projectile

Explosive Beginnings

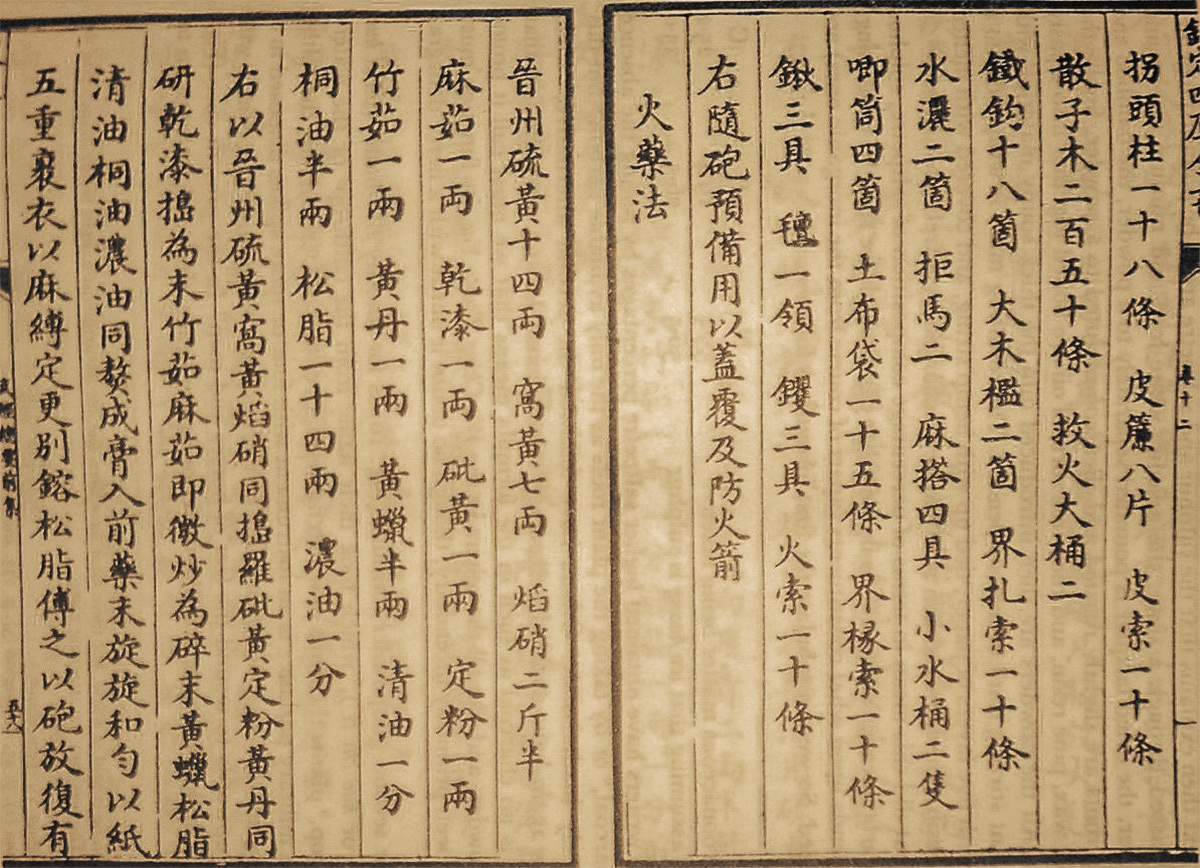

There is some historical debate about when and where black powder — that magic mix of sulfur, carbon, and potassium nitrate (aka saltpeter) — was first discovered. The most widely accepted theory is that it came from China in the 900s.

I say “discovered” and not “invented” because no one was setting out to create something with the properties of black powder. The Chinese were trying to develop an immortality elixir from sulfur, saltpeter, and honey. In what is perhaps history’s biggest irony, they instead stumbled upon something that would take the lives of tens of millions of people in the coming centuries and save and sustain countless others through defense and hunting.

Before firearms were invented to channel and focus the explosive power of the volatile mixture, black powder was first used to create incendiary bombs. Today, we would equate what they made with black powder in this era akin to hand grenades and explosive artillery shells. They went boom and set shit on fire when they did.

GOOD GEAR – Stand Out Looking Stylish With the BRCC Keystone Hat

Perfecting the Black Powder Recipe

A philosopher named Roger Bacon recorded the first known Western recipe for black powder in 1242, and it definitely didn’t contain Chinese honey!

Consisting of charcoal, sulfur, and potassium nitrate, Bacon’s formula for true black powder hasn’t changed in more than 800 years. Hey, if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it!

RELATED — Uintah Precision Introduces Cool New Ar-15 Muzzleloader

First Black Powder Firearms

The first devices that launched a projectile from some kind of tube propelled by burning black powder were, of course, cannons.

In their most primitive iterations, the first real black powder firearms were what we know today as hand cannons. The earliest surviving examples of hand cannons date back some 800 years or more.

They are, essentially, just scaled-down, smoothbore cannon tubes mounted to pieces of wood.

A user would pour black powder down the tube, load it up with rocks, nails, or anything else that’s hard, heavy, and hurts, ignite the charge through the touch hole in the tube, and pray that it only explodes from the end facing away from them. At various stages and places, wadding and other elements were added.

The blunderbuss is one of the less primitive hand cannons, but it still operated on the same basic principle — a black powder charge propelled…whatever you could stuff down the barrel.

GOOD GEAR – Power Your Adrenaline-Fueled Days With the BRCC CAF Roast

Playing With Matches

The first devices we would consider akin to rifles were matchlock muskets. They were held like conventional rifles, had hand-operated triggers that deployed the ignition source, and had a buttstock for the shooter’s shoulder, which also meant looking down the bore to aim.

Matchlocks got their name from the hemp or flax match cords used to ignite the charge. The cords were treated with potassium nitrate and burned much like a slow fuse. A curved lever called a serpentine held the burning cord. When the trigger was pulled, the serpentine lowered the burning end of the match cord into the powder charge and fired the gun — in principle and operation, the matchlock was still not much different from a cannon.

The concept was simple and relatively effective when everything went right, but it certainly had its drawbacks. First off, the shooter had to carry around a lit match cord at all times. This can be a recipe for disaster when carrying around loose black powder. Beyond that, the lit cord was susceptible to inclement weather, and in close quarters at night, the glow of the line could give away the shooter’s position. Plus, it ain’t so easy to get a match cord lit or relit when your primary firestarter is steel, flint, and some char cloth instead of a Bic.

With matchlocks came the first shooting sticks — out of necessity — and, by extension, bipods. The guns were incredibly bulky and heavy, so shooters carried a rest with them to make aiming easier.

Early on, they were monopods with a forked head, but traditional shooting sticks came along in short order. Unlike today, though, these things weren’t collapsible or lightweight, so it added another bit of bulk to a shooter’s kit.

Refinements were obviously needed, but the basic pieces of what would become the black powder rifle had been assembled in the matchlock.

RELATED — 45-70 Govt: One of the Few Black Powder Era Survivors

Reinventing the Wheel

To eliminate the shortcomings of the matchlock, a new design known as the wheel lock emerged around 1500.

In terms of complexity, it was the exact opposite of the matchlock. The wheel lock mechanism used friction instead of a burning cord to ignite the powder charge.

A steel wheel was wound up tight with a spanner wrench, and a piece of pyrite (fool’s gold) was placed in the hammer’s jaws. When the shooter pulled the trigger, the steel wheel would spin against the pyrite, creating a flurry of sparks that ignited black powder in a pan. Once ignited, the black powder would flash through a small touch hole and ignite the main charge in the rifle barrel.

While no longer carrying around a lit match cord was nice, the wheel lock was far from perfect, and operating such a gun was a slow deal.

First, a shooter needed the spanner wrench to wind the wheel and make it ready to fire. If the wrench got lost, the gun became a club. Also, if the spring broke, there was no way to spin the wheel and spark the pyrite. In short, it wasn’t a very reliable design.

Ergonomics were also less than ideal with matchlock rifles. Buttstocks were often large and blocky and dug into the shoulder; the idea of gentle angles in the wrist for a more comfortable hold didn’t exist; and many times, the overall artistic appeal of the gun took precedence over functionality. Since black powder rifles of this era were expensive, they were also often beautifully inlaid with precious metals and stones. They looked great, but it did nothing for performance.

GOOD GEAR – In Honor of Our Mainstream Media Friends, Wear the BRCC Trust Us T-Shirt

Flash in the Pan

Around 1600, the first ignition systems we think of today as flintlock designs emerged. Compared to the complexity of the wheel lock mechanism, the flintlock design was elegant in its simplicity.

There are several different subset varieties within the flintlock designation, but for our purposes, we’ll just call them all flintlocks because they all operate in essentially the same manner.

A priming charge of black powder sits in the pan, and a steel frizzen snaps closed over the top of the pan to keep it in place. A hammer with jaws tightly holds a piece of shaped flint wrapped in some kind of cloth so it doesn’t crack.

When the trigger is pulled, the hammer flings that flint with great speed into the steel frizzen. This pushes the frizzen forward, exposing the powder in the pan while also raining down a shower of sparks from the flint scraping against the steel. This ignites the priming charge in the pan, which travels into the barrel to ignite the main charge and fire the gun.

Sometimes the powder in the pan would ignite; other times, it would fail to ignite the main charge and the gun wouldn’t fire. This is where we get the phrase “flash in the pan.” Common causes for ignition issues included too little powder in the pan, a pan poorly aligned with the hole in the barrel, or a delayed ignition from too much powder in the pan.

Perhaps the most cumbersome part of the flintlock was the trial and error required to get the load just right. Back then, just as today, different amounts of powder and different bullet weights had a big impact on flintlock rifle performance. Whereas today we have factory-loaded cartridges that have been perfected for performance, back then it was up to the individual shooter to try things out and find the right balance for the perfect load. Even one or two grains of powder in the flash pan could make a huge difference.

In terms of black powder ignition methods, the flintlock enjoyed the longest life span, topping out at around two and one-quarter centuries. It carried firearms through the smoothbore musket era and into the time of the first black powder rifles, which, of course, had rifled barrels instead of smoothbores. Firearms became weapons that could be fired at range accurately for the first time, rather than close-quarters or salvo weapons fired in volleys.

RELATED — GoEx Plant To Be Revived: American Black Powder Is Back in Business

Black Powder Rifle Evolution

While true rifles existed during the American Revolution, most soldiers on both sides were still shooting smoothbore firearms. They were faster to load because there was no resistance in the smooth barrel, and they could shoot a wide variety of projectiles. Essentially, if it fits, it shoots. Of course, the smooth bore had drawbacks — namely, accuracy at distances out past 75 yards.

Once rifling in gun barrels became commonplace, everything changed. It was with the addition of those lands and grooves that we truly got the difference between rifles and muskets. (Though it must be noted that the term “musket” can also be used to describe a rifle with an exceptionally long barrel.)

Rifled guns allowed for much better accuracy and also brought about the idea of different guns for different uses. Whereas a smoothbore fowler of large caliber would have previously been used for everything from squirrels to ducks and deer, black powder rifles served specific purposes.

A .32-caliber rifle was perfect for squirrels and a .54-caliber rifle was better suited to deer or elk. The accuracy that rifling gave to these guns was important because the loading process was slower than that of a musket. To be sure, a musket wasn’t fast by any means, but it was faster. A rifled shot gave a higher probability of a kill shot, which outweighed the drawback of load time.

GOOD GEAR – Show That You Love BRCC Coffee With the BRCC Vintage Logo Ladies T-Shirt

The Golden Age of Black Powder Rifles

After the American Revolution and into the early Republic, we see what is regarded as the golden age of black powder rifles. Most often, these rifles are referred to as Kentucky rifles or Pennsylvania rifles, though they were made in every state. The designs had been slicked down and refined, and, while often heavily embellished and adorned, these aesthetics worked with the ergonomics and not the other way around.

Once percussion ignition came on the scene in the first quarter of the 19th century, the flintlock guns were either converted or abandoned, depending on the shooter and their budget. The elegance of the guns remained — just the way the powder ignited changed.

RELATED — Most Expensive Guns: The 6 Priciest Firearms Ever Sold at Auction

Frontier Guns

It’s at this time that we get what is perhaps the most iconic gun of the early American frontier: the Hawken rifle. Named after brothers Jacob and Samuel Hawken from Missouri, their rifle design was made by countless thousands of gunsmiths and used all over.

Visually, they lack a full stock, opting for the weight savings of a shorter half-stock that was paired with a shorter barrel. This made the gun easier to maneuver in the woods while still maintaining accuracy and reliability thanks to rifling and percussion ignition.

Despite their shorter overall size, Hawken rifles are regarded to this day as some of the most accurate black powder rifles ever made.

This is also the era in which people start really drilling down into ways to make their guns more accurate. We see the introduction of sophisticated adjustable sights — both front and rear — becoming increasingly popular.

They were a big part of why the American bison almost went extinct. Commercial hunters could harvest the behemoths from longer distances, which allowed them to shoot more of them without disturbing the herd or risking getting charged and killed.

GOOD GEAR – Wear the Perfect Hat for Range Day With the BRCC Leather Patch Trucker Hat

Convenience of a Cartridge

People often mistake the self-contained metallic cartridge as a relatively new invention. The cartridges we use today have changed very little since their introduction when Andrew Johnson assumed the presidency in the wake of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination with a percussion pistol loaded with loose black powder and a round ball.

While advances in metallurgy have strengthened cartridge designs to safely handle smokeless powder and increasingly hotter, more powerful loads, the original cartridges were loaded with traditional black powder.

This meant that even though you had the convenience of self-containment, you still had to deal with all the smoke. While this visual obstruction was less of an issue for hunters, who usually fired only one or two shots, it was hell on the battlefield.

Giant clouds of smoke obscuring soldiers is most often associated with the Revolution or the Civil War, which is certainly true, but it was an even bigger problem in the cartridge era when soldiers were firing the same smoky powder but much more rapidly.

Nonetheless, it was a tremendous leap forward in convenience. Now you could carry a Colt Single Action Army revolver and a Winchester Model 1873 rifle and quickly load them with the same .44-40 cartridges.

RELATED — Hunting History: How Firearm Tech Changed the Way Americans Hunt

Back in Black

By the end of the 1800s, smokeless powder emerged on the firearms scene. This new powder had supplanted more traditional black powder loads in most shooting markets within a few decades. Smokeless powder guns could be loaded hotter and heavier, generating faster speeds and greater energy delivery.

Despite the benefits of smokeless powder, traditional black powder rifles have never entirely disappeared, partly due to an “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” mentality. Black powder rifles worked just fine before, and that didn’t change just because smokeless powder emerged on the market.

Traditional black powder rifles, shotguns, and handguns enjoy a rich subset among the collecting, shooting, and hunting communities, but they’re far from the only black powder firearms available today.

Modern muzzleloaders — some of which use traditional black powder and others that use modern synthetic black powder substitutes — are incredibly popular today. The number of companies that have spent big bucks on developing cutting-edge technology that fits into the world of centuries-old technology is really quite impressive.

Still, some people eschew these modern advancements and still cling to actual, traditional black powder rifles. There are plenty of hunters who still only use primitive flintlock rifles and won’t even dare touch a cartridge gun — black powder or not.

It’s a solid endorsement of the black powder rifle that, after more than a millennium, people are still using this humble workhorse of a firearm, even with all of the modern advancements that stand upon its shoulders.

GOOD GEAR – Wear the Perfect Veteran Hoodie With the Premium BRCC Pullover Hoodie

The Collapse of Civilization and Black Powder’s Resurrection

It doesn’t matter how hardcore of a prepper you are, with pallets of ammo, bullets, and primers squirreled away in a super-secret bunker. The simple fact is that if the world collapses, you’ll eventually run out of loaded ammo and individual components to replenish what you’ve shot.

When this happens, people will once again turn to black powder. This is because it can be made at home with relative ease in comparison to smokeless powder. Some people have tried reloading .223 cartridges with black powder to see how it works. In short, it does, but it’s not ideal.

This is why traditional, muzzleloading black powder rifles will once again rule the day when society collapses. You can make your own black powder, knap your own flints, and melt down metal objects of all kinds to fling at your enemies from the tribe in the next subdivision.

The whole world is just one big solar flare away from putting us all back into a world where the flintlock black powder rifle will once again be man’s most trusted and valuable tool.

RELATED — The Many Guns of John Wayne on the Big Screen

Don’t Wait — Try It Today

You don’t have to wait for World War III to kick off before you give black powder rifles a try. In fact, waiting for that time is probably the worst thing you could do. So why not give a black powder rifle a go today. There are plenty of affordable flintlock and percussion rifles from companies such as Traditions and Dixie Gun Works that you can grab and start shooting today.

Or, you can go more old school and build your own black powder rifle from a kit. Basic ones can be had from the companies above, but you can really try your skills with a kit from someone like Kibler’s Longrifles. There are even plenty of places where you can take classes to learn how to build them.

READ NEXT — Muzzleloaders in Movies: Hollywood’s Coolest Smoke Poles

Comments