The first time a Marine Corps sergeant instructor told me that chow is continuous in the field, I remember thinking, “That’s unexpectedly considerate; I get to eat whenever I want.” In reality, no time is set aside to eat, so figure it out on your own and don’t waste anyone’s time complaining about it. Choking down bad food in a hurry is a time-honored military tradition. While food has historically been a sore subject among combat troops, the mess kit they ate from was often a prized possession.

These days, American service members scrape questionable substances out of stiff Meal, Ready-to-Eat (MRE) pouches with a plastic spork. Previous generations used the same kind of metal mess kits that kept troops fed in the jungles of Vietnam, the American plains, and every conflict in between. Before that, mess kits were more of a do-it-yourself affair. What did these mess kits look like, and what kind of food did they serve up?

I dug deep into Army records and historical photos to find out. Getting in touch with the past might make you realize that you have more in common with early American soldiers than you think, and you might learn a few tricks you can use when coming up with your own meal plan.

GOOD GEAR – Keep That Freedom Engine Running With the BRCC Freedom Fuel Coffee Roast

What Is a Mess Kit?

Before the era of MREs, the U.S. military fed its service members a more varied diet — at least when it came to quality. Rations of meat, bread, and vegetables could be fresh off the farm or downright hazardous prior to standardized, prepackaged food.

To eat these meals, service members would use their own dishes and flatware. They might cook their own food, too. This gear formed an aptly named mess kit. Designs have changed throughout the years, but the concept lives on in the camping mess kits available today.

RELATED – Illuminating Survival: Learn From Light Sources Used by Medieval Troops

Revolutionary War Mess Kits: Bring a Sack Lunch

The entire Continental Army was a bit of a hodgepodge affair, and the troops’ mess kits were no exception. Soldiers carried whatever cookware and utensils were available in a haversack — a small linen bag with a strap to carry it over the shoulder or cross-body. They used these kits to cook personal meals over open fires. The bags weren’t standardized until 1851, when the U.S. Army chose a specific size and gave the linen a treatment of linseed oil for color and waterproofing.

While mess kits were a free-for-all, the Continental Congress did attempt to standardize the food soldiers ate. The official Continental Army daily ration included one pint of milk, one quart of spruce beer or cider, one pound of flour or bread, and either one pound of beef, one pound of salted fish, or 12 ounces of pork. Each soldier got three pounds of peas or beans and one pint of rice per week. The ration also called for a small amount of molasses but didn’t specify a quantity.

In practice, the Continental Army struggled to acquire adequate food, and soldiers frequently relied on donations from sympathetic civilians.

GOOD GEAR – Show Your Commitment to Black Rifle Coffee With the ARROWHEAD T-Shirt

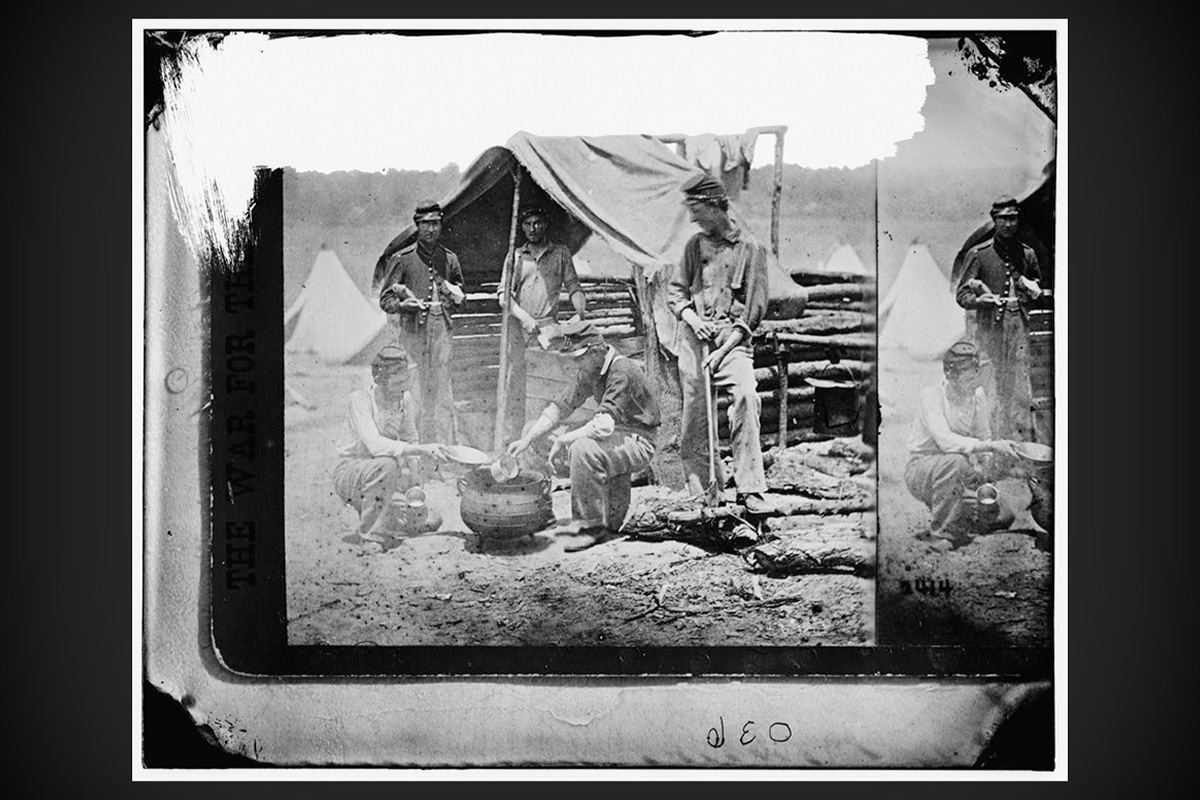

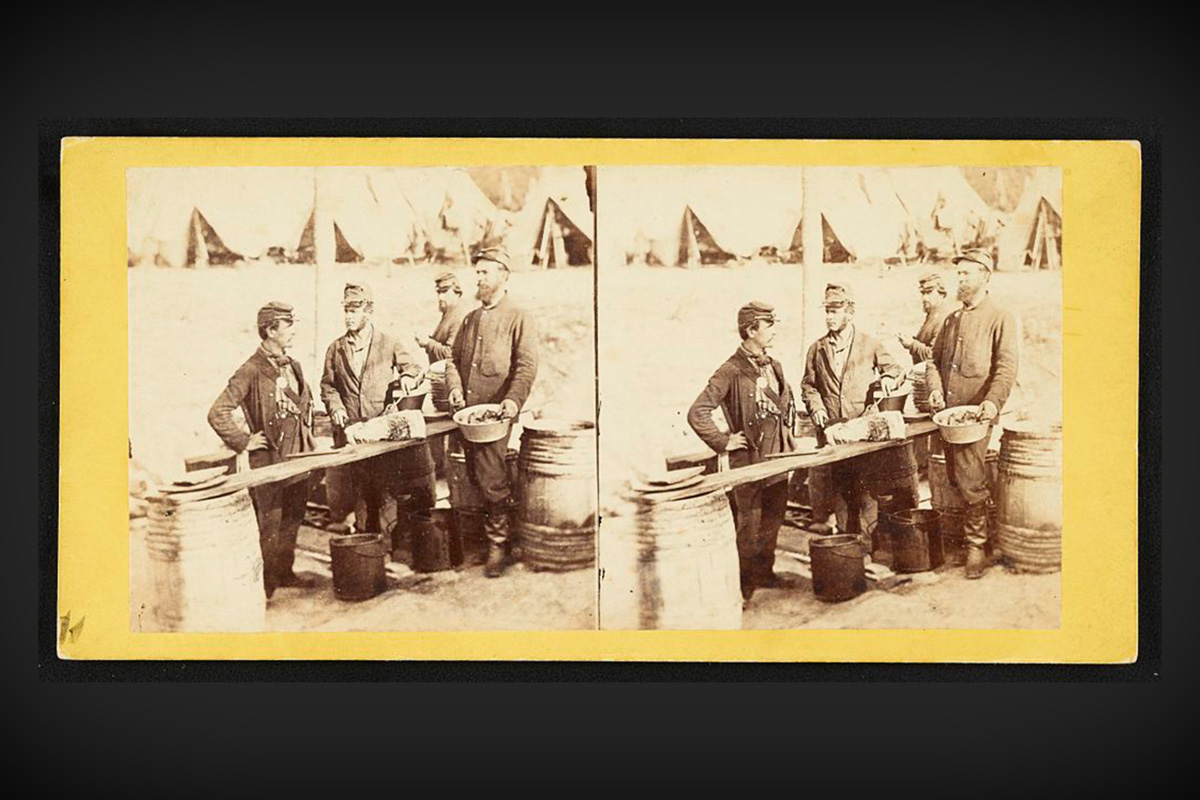

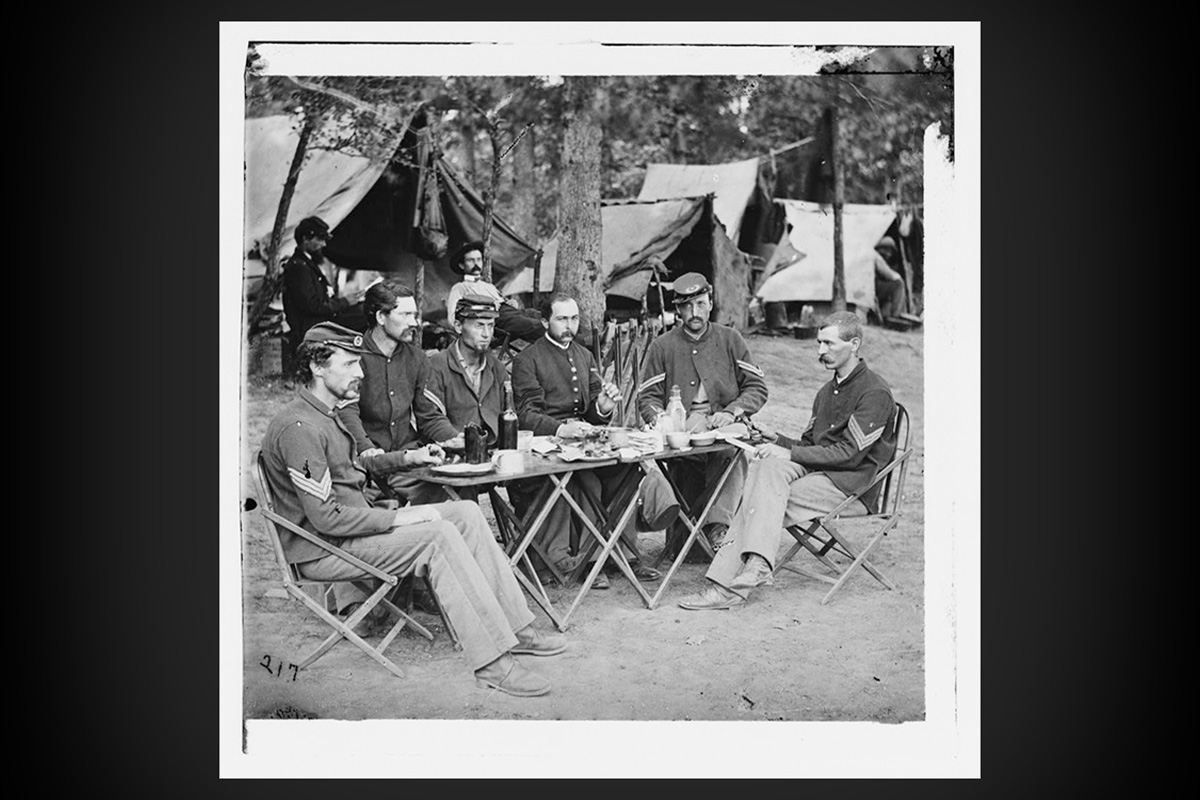

Civil War Mess Kits: Oh Good, More Hardtack

After the Continental Army became the U.S. Army, its rations got small changes during the early 1800s (most notably the addition of rum). After the Army accepted a standard haversack in 1851, it also began issuing standardized tin canteens in 1858.

Just before the outbreak of the Civil War, the canteen design received a ring of stamped concentric circles to make it more rigid. Canteens originally came with a blue wool outer layer and a white linen strap, but various quartermaster depots used several colors and materials by the war’s end. Soldiers could still use their own cups, plates, and utensils.

For soldiers in the Union Army, the daily ration must have seemed like a feast during the early days of the Civil War. Congress allotted each soldier 20 ounces of beef, 22 ounces of flour, 7 ounces of potatoes, 2.65 ounces of dried beans, 1.6 ounces of green coffee beans, and small amounts of sugar, salt, pepper, yeast, and vinegar per day. Provisions also included a candle and soap to encourage good hygiene.

As the war went on, carrying the daily ration proved impractical. The Army replaced fresh beef with jerky. Dehydrating vegetables cut down on their size and weight. Most famously, soldiers began making and carrying hardtack. The simple recipe required only flour and water — plus a pinch of salt for those with a flair for the culinary arts — and the resulting biscuit could remain safe to eat for long periods of time. You can still find hardtack from the Civil War in museums today, so that should tell you how delicious it was.

Soldiers on both sides of the Civil War prized coffee. Union soldiers collected a small number of whole beans each day since they preferred to brew their own coffee. Both armies took food from nearby farms but getting imported items, including coffee, was almost impossible for the Confederate Army thanks to the naval blockade that cut off the southern states from foreign trade.

Confederate soldiers resorted to brewing all kinds of alternatives, including dandelion, chicory, and acorns. Given the present lack of hipster dandelion shops, it’s safe to assume that the results were not good.

RELATED – Making a Hiking Road Trip Food Plan – Adventure 101

Plains Wars Mess Kits: What the Hell Is a Meat Can?

As the U.S. Army put the Civil War behind it and turned west, mess kits got a series of updates, leading up to the Infantry Equipment Board of 1878. New gear included a redesigned haversack with metal hardware, canvas instead of linen, and three internal compartments instead of one. For the first time, soldiers carried standard-issue utensils and a tin cup. The canteen got an update as well in the form of cloth insulation, a brown fabric cover, and a chain to secure the cap.

Given the long distances that soldiers had to cover without resupply, they took on more responsibility for carrying their own rations. For a short time, the tool they used was the 1872 meat can. This small metal box kept uncooked meat from getting grease all over the inside of a soldier’s haversack. By 1874, the Infantry Equipment Board replaced the meat can with a metal mess kit consisting of two oval trays that locked shut, using the handle to create a sealed container.

Unfortunately for soldiers sent to the western frontier, standard Army rations didn’t improve after the Civil War. Hardtack and salted meat made for an unhealthy diet that led to scurvy if soldiers didn’t intervene by gathering food from the surrounding land. Western garrisons often featured farm plots that grew enough food to keep active soldiers in good shape. Dehydrated vegetables and meat served as trail rations that could remain safe to eat for weeks on the prairie.

GOOD GEAR – If There Is Life on Mars, Make Sure It’s Caffeinated With the BRCC Caffeinate Mars Mug

Ditching the Mess Kit: Meals Ready to Endure

If you think the revised meat can of the American west looks familiar, you’re right. It stayed in use by the U.S. military for roughly a century, and the design is still common in the camping world. Utensils and canteens came and went, as did miscellaneous items like the M-1910 condiment can, the M-1916 bacon can, and the canteen cup stove.

The modern canteen shape first saw use in World War I, although the design used metal rather than plastic. The modern canteen made from green plastic came into use in 1961.

From a health perspective, the rations issued during World War I were a vast improvement over the meager food that sent soldiers scavenging during the decades prior. Rations were also better prepared to last in a forward environment thanks to improvements in preservation techniques and packaging. Beginning in World War II and continuing through Vietnam, soldiers ate C-Rations, K-Rations, and Meals, Combat, Individual (MCI).

These prepackaged daily rations varied in size, but individual components were small enough to fit in a soldier’s pocket. Meals commonly included canned meat or eggs, crackers, fruit, and condiments. The Quartermaster Subsistence Research & Development Laboratory deserves credit for considering morale part of a service member’s combat readiness and included desserts, cigarettes, matches, and toilet paper in field rations starting in the 1930s.

By the 1980s, mess kits were nearing the end of the road. Once service members could heat and eat their meals directly from the pouches the food came in, there was no need for bulky mess kits. Anyone who has field-stripped an MRE knows that a plastic spork and a few pouches of food are a lot easier to carry than camping utensils and a pair of metal trays. Not having to do dishes in the field is a plus, too.

So, with all that advancement, does the U.S. military still issue mess kits? The short answer is no, not really. The military replaced MCIs with MREs in the 1980s, at which time the military mess kit became obsolete. There are still examples in circulation at surplus stores, and new takes on the classic design remain popular for camping. Even if you pack dehydrated camping food, it can be nice to cook it in a mess kit over a fire instead of scooping food out of a pouch if you can spare the extra weight.

RELATED – VSSL First Aid Stash and Stash Mini: Survival in a Can

Are Aluminum Mess Kits Safe?

Metal mess kits have a long track record of success because they’re durable, easy to clean, and relatively light. Aluminum mess kits are still popular for camping and backpacking since they’re lighter than a stainless steel mess kit and cheaper than titanium.

They’re safe to use, but certain nonstick coatings can be a problem if they’re damaged. Know what you’re using and protect it with nonmetallic utensils, if necessary, or use bare metal. Some mess kits now use titanium, which is significantly stronger than aluminum and can be lighter since they use less material. Heat-resistant silicone options are available, too.

GOOD GEAR – Look Stylish and Stay Warm With the BRCC Women’s Mountain Crop Hoodie

What Should Be in a Mess Kit?

At a minimum, a mess kit should include everything you need to cook a meal, something to eat from, something to drink from, and utensils. Most ready-made mess kits are designed to be lightweight, compact, and fairly easy to use for camp cooking. Stay away from gimmicks.

The classic lineup for camping trips is a cooking pot for cooking stew and soup and boiling water, a frying pan, and a pot lid that can sometimes double as a plate and a lid for the pan. And, of course, a stove of some kind, unless you plan to cook on open fires only.

All this gear should be small, light, and strong. Picking the right balance of those traits will depend on your planned activities. Backpackers typically prefer a Jetboil for a stove. Overlanders and car campers can carry more extensive cookware that can sometimes resemble a chuck wagon, including full-size pots and pans and even cast-iron skillets.

Kits like the Sea to Summit Alpha Pot Cook Set and Snow Peak Starter Kit are a great way to get the essentials (minus utensils) in a compact package. For the best results, use these with a backpacking stove or ditch the gas with a Solo Stove Lite. You can also get everything you need from a full kit like the MSR PocketRocket Stove Kit.

READ NEXT – Essential Gear for Perfect Backcountry Coffee

Comments