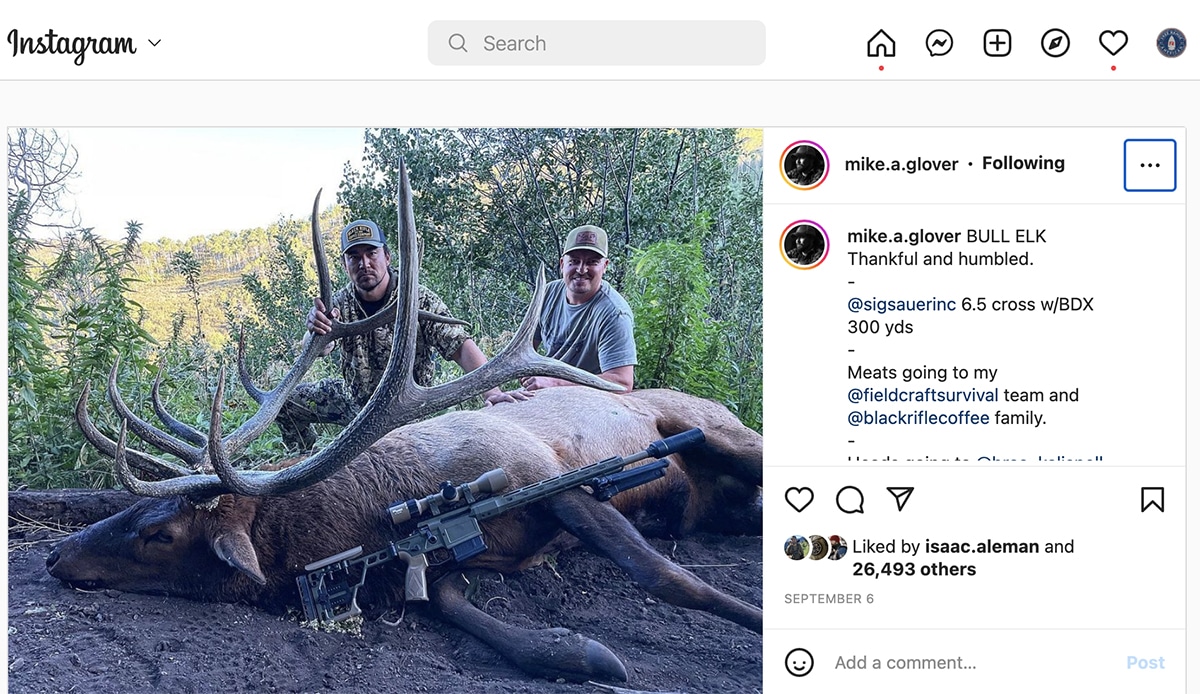

The Instagram police finally came for Mike Glover last week. His account vanished one morning after a barrage of reports triggered an auto-ban in the social media platform’s system. It wasn’t because of a tactical firearms-training photo or a video posted by the former Green Beret and CEO of Fieldcraft Survival — it was because of a bloodless field photo he posted of himself with a beautiful bull elk he shot in early September.

“I was just trying to thank everyone who supported me in the hunt and express how humbled and honored I was to have the opportunity to take a mature bull elk — and that was flagged for gun sales.”

— Mike Glover

After more than a week, the host of Free Range American’s Fieldcraft Pro Tips video series got his account back up and running, thanks to what he calls “inside help,” but hunting photos on social media are removed and flagged as inappropriate content all the time. In some cases, outdoorsmen and women have had their entire accounts deleted without explanation and without breaking any of the platform’s rules. For them, the bans can go on for months or even indefinitely.

Whether you’re a critic or a fan of the stereotypical “grip and grin” hunting photos, once September rolls in, social media is flooded with them. Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube, and other platforms have become virtual campfires where outdoorsmen and women gather to share the highs (and sometimes the lows) of their hunting experiences.

Human beings’ desire to share stories of the hunt is nothing new; we’ve been doing it since the first caveman smeared charcoal to form an image of a woolly mammoth on the walls of some prehistoric cave. Only now, we’re using digital pixels on social media platforms to do the same thing.

If you’re a hunter, chances are good you’ve shared an outdoor experience or two on a social media account. Imagine waking up the morning after posting pictures of your latest hunting adventure and finding your entire IG account has vanished with no explanation. That’s precisely what happened to Glover.

The photo that triggered the suspension was posted on Sept. 6 to Glover’s personal Instagram account (@mike.a.glover) and featured a gorgeous 6-by-6 bull elk he killed in Utah and the suppressed SIG Sauer Cross rifle he used to shoot it.

“I was taken aback by it,” Glover told Free Range American. “Instagram’s algorithm is known to take down posts that have to do with hunting, but it’s not common. A lot of hunters post pictures of game animals. Instagram might suppress those photos in their algorithm, but they won’t flag or ban the account.”

As far as his followers were concerned, Glover’s account disappeared into thin air, taking more than four years of content with it. The auto-generated message from Instagram claimed Glover’s elk hunting post violated their community guidelines because it “was a promotion of gun sales.”

Glover is well-known for posting photos of firearms on his Instagram account, so it was a major surprise that a hunting photo got him shut down.

“I’ve done posts where I’m kind of riding the line, but this post was different,” Glover said. “I was just saying how humbled I was to have the opportunity to hunt. I said thank you to some people and gave a list of the equipment I used, including the type of rifle I used. That’s it. It had nothing to do with marketing a rifle.”

“I was just trying to thank everyone who supported me in the hunt and express how humbled and honored I was to have the opportunity to take a mature bull elk — and that was flagged for gun sales.”

Before his account was suspended, the elk photo in question had garnered more than 27,000 likes and had over 600 comments.

This isn’t the first time Glover’s account has been flagged by Instagram. He’s had 17 temporary bans.

How Coordinated Attacks Can Get Accounts Banned

Baker Leavitt is the CEO of Digital Mongoose LLC, a social media consulting firm that handles the social media accounts of 27 different companies in the hunting and outdoor space, and he’s the head of partnership development for FRA’s parent company, Black Rifle Coffee. He believes Glover’s account was basically attacked by a coordinated team of internet warriors.

“Enough people disliked what he was putting out, so they started doing coordinated raids on his accounts by reporting the same post at the same time,” explained Leavitt.

Sometimes called brigading or dogpiling, a raid, as Leavitt describes it, is a social media harassment technique in which a group coordinates a virtual assault on a specific user at a specific time, usually by mass reporting the account or individual posts from the account as “harmful, misleading, or inappropriate.” It happens in some form on every social media platform.

The platform’s algorithm sees the spike in reports and automatically disables the account once specific parameters are met. The account then gets put in line to be reviewed by a human being.

“All of a sudden, Instagram gets a notification that 300 people have reported a post within 5 minutes. Then the post gets taken down, and because there are so many reports, they just automatically suspend the account until they have time to review it,” Leavitt explained.

Leavitt said that the content-reporting and auto-ban systems that Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and TikTok have in place are mostly based on the honor system: A user sees something that they feel is offensive or violates the platform’s rules and they report it because moderators can’t be everywhere at once. But now, the reporting system is being exploited.

“They didn’t come up with these systems and processes thinking that people would start weaponizing social media, but that’s what they’ve done,” he said.

IG Outsources Content Moderation to Other Countries

Because a lot of crazy stuff gets posted and consequently reported on Instagram, the review process can be hella long. The process is further complicated by the fact that Instagram is outsourcing its content moderation. When a ban is challenged by a poster, the individual reviewing the case is probably doing the moderating from somewhere outside the US, usually India or the Philippines.

Although Glover’s Instagram account was finally restored after about eight days, that isn’t the typical experience. It took him more than a week of jumping through hoops and a few good connections to get it done so quickly. The average person can face a much longer, more difficult process.

“If I didn’t have inside help, it would never have happened. This is crazy stuff,” Glover said. “The person doing my review was from Singapore. We had to go back and forth in different time zones trying to defend this, but we were debating an entirely different culture that is now responsible for moderating Americans.”

Although it is common practice for American hunters to pose with the bow or rifle they used to take a big-game animal, other cultures may look at such photos differently — indeed, many in the US find photos like this offensive.

Leavitt believes those who attacked Glover’s Instagram account were probably animal rights zealots.

“The animal rights people and the anti-hunting crowd are malicious,” he said. “Those people truly believe that if you kill an animal, you deserve to die.”

Targeting hunters on social media certainly isn’t isolated to Glover’s experience. One of the most severe cases in terms of repercussions is that of Melania Capitan.

The anti-hunting messages that flooded the Spanish hunter and blogger’s social media pages following her 2017 suicide definitely seem to support Leavitt’s claim. When the news broke that the young 27-year-old took her own life after enduring severe cyberbullying, many posts were left on her social media pages celebrating her tragic suicide, presumably by many of the same people who bullied her in the first place.

Cable Smith, a dedicated outdoorsman and the host of the Lone Star Outdoors Show, also had his Instagram account fall to an angry mob.

“Last January, I was sitting in a duck blind and went to get on Instagram. I was going to take a picture of my dog with the sun coming up,” Smith told Free Range American. “My account was just gone. Not suspended, just gone. No explanation. Nobody to contact. No recourse. No nothing. They just completely deleted it.”

One of the photos that triggered the demise of Smith’s account was a trail camera image of a buck.

“I put a caption on it that basically said, ‘I’m thinking about taking this buck this year, or I might let my son kill it, depends on how the season plays out,’” Smith said. “They flagged it and said that I was ‘promoting crime and coordinating harm.’”

Like Glover, Smith was eventually able to retrieve his account, although it took 30 days and some professional connections to make it happen. Still, the damage was done; his account has never been the same.

What Are Shadowbans and Are They Real?

Unlike an official ban, shadowbanning is a form of censorship some people claim social media platforms use to prevent members of an online community from seeing a user’s posts, regardless of the number of followers they have.

Although Instagram’s CEO Adam Mosseri adamantly claims shadowbanning is not a thing, many social media users, including Smith, aren’t buying it.

“I had 145,000 followers, and the page was just on fire, adding a couple of thousand followers every month,” he said. “In the past two years, it hasn’t grown at all. In fact, I’ve lost 1,000 followers. When it’s trending up for a decade, and I didn’t change the content I was posting, it has to be something on their end.”

Not only has Smith’s growth stalled, but his engagement and reach have plummeted.

“Two years ago, my posts would generally get around 3,000 likes. Now it has to be a crazy picture for anything to happen. I might get like 500 likes with 144,000 followers,” Smith said.

Social media censoring of hunters is concerning beyond how it limits our ability to brag to our online buddies.

Robbie Kroger, the founder of Blood Origins, a nonprofit dedicated to conveying the truth about hunters, believes that “social media is the most important battleground for hunting in the world today.”

While fanatical anti-hunters have used the networking power of social media to silence hunting voices, hunters are tapping into that same power and using it to preserve our hunting heritage.

Thanks in part to social media networking, hunters have recently organized to defeat anti-hunting legislative strikes like California’s attempted bear hunting ban and the proposed closure of Federal public lands in Alaska to non-local hunters.

While it may be tempting to throw up our hands in frustration over how social media sometimes handles hunting content, these public platforms are often the best way to inform the like-minded masses about orchestrated anti-hunting attacks. For that reason, social media censorship of hunting voices should have us all concerned, even if we’ve never posted a dead animal photo.

READ NEXT – A Bowhunter’s Paradise: Caribou Hunting in Greenland

Comments