I was 19 when my uncle handed me my grandfather’s Winchester Model 94 lever action.

It was a beat-up old .30-30 hunting rifle that looked like it had been dragged behind a truck over a gravel road. It had mostly been sitting in a dusty corner unused for more than a couple of decades. It was dented and scratched, the blued steel freckled with rust.

My uncle claimed it “had a lot of character.”

I’d had my heart set on a shiny new semi-automatic .30-06, a sleek and sexy grown-up gun, to tote in the woods, one with a high-class scope. I thought that was the kind of firearm that would turn heads at the gun range and the checking station, the kind of hunting rifle that said, “Now, that’s a serious deer hunter.”

My dad had let me carry his beloved .30-06, a Remington Woodsmaster Model 742 with a Bushnell scope, once — while he dragged out a fat doe he’d killed way back in a mountain holler at least a mile and a half from the road. He cussed me the whole way out.

“Holy Hell! If you’re going to slide down the goddamn mountain, could you at least not fall on my rifle?”

We were making memories.

But people older than me decided without my input that a cool new .30-06 would be too much gun for me. At the time, I was a wispy young girl who tipped the scales at a solid 100 pounds, but only after a good meal. So instead, I got a dusty old lever action cowboy gun.

While I tried to hide my disappointment, it was probably palpable. I honestly didn’t know the value of what had been placed in my hands.

RELATED — How the Winchester Model 70 Nearly Made Lever Actions Obsolete

In the Beginning

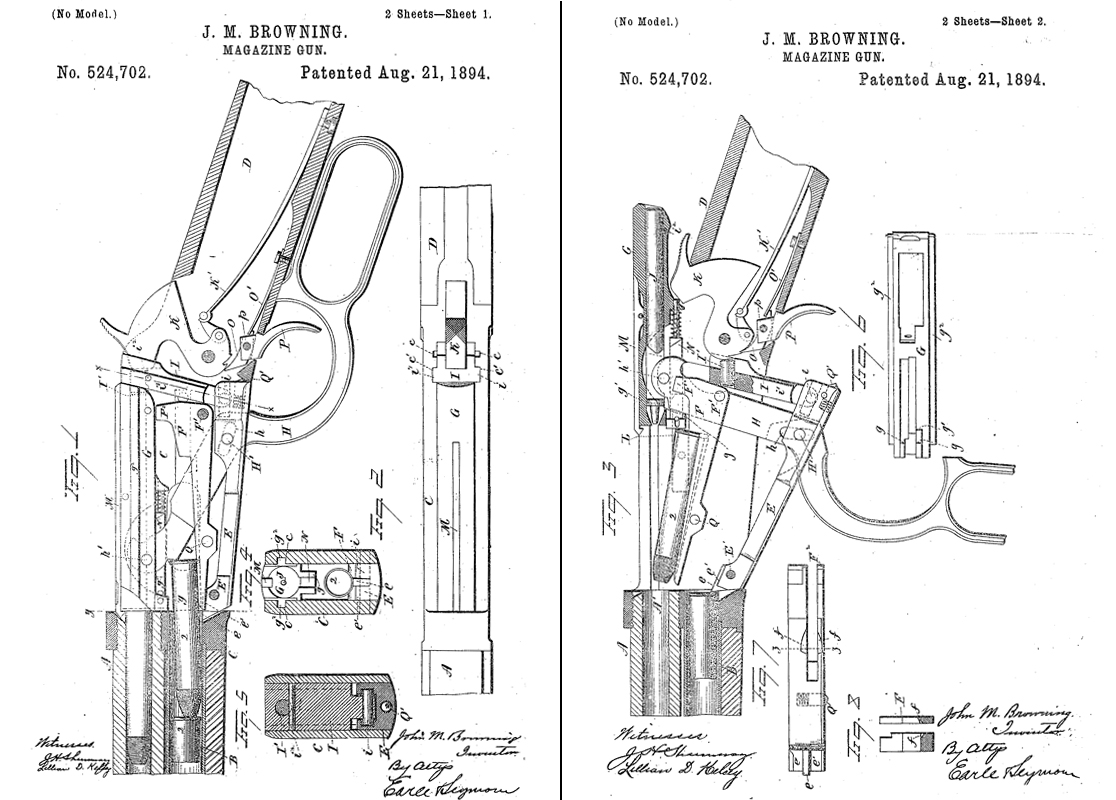

John M. Browning designed the Winchester Model 1894. A savant of firearms engineering, we have Browning to thank for the Colt 1911, the M2 machine gun, at least 40 other guns, and more than a half dozen cartridges.

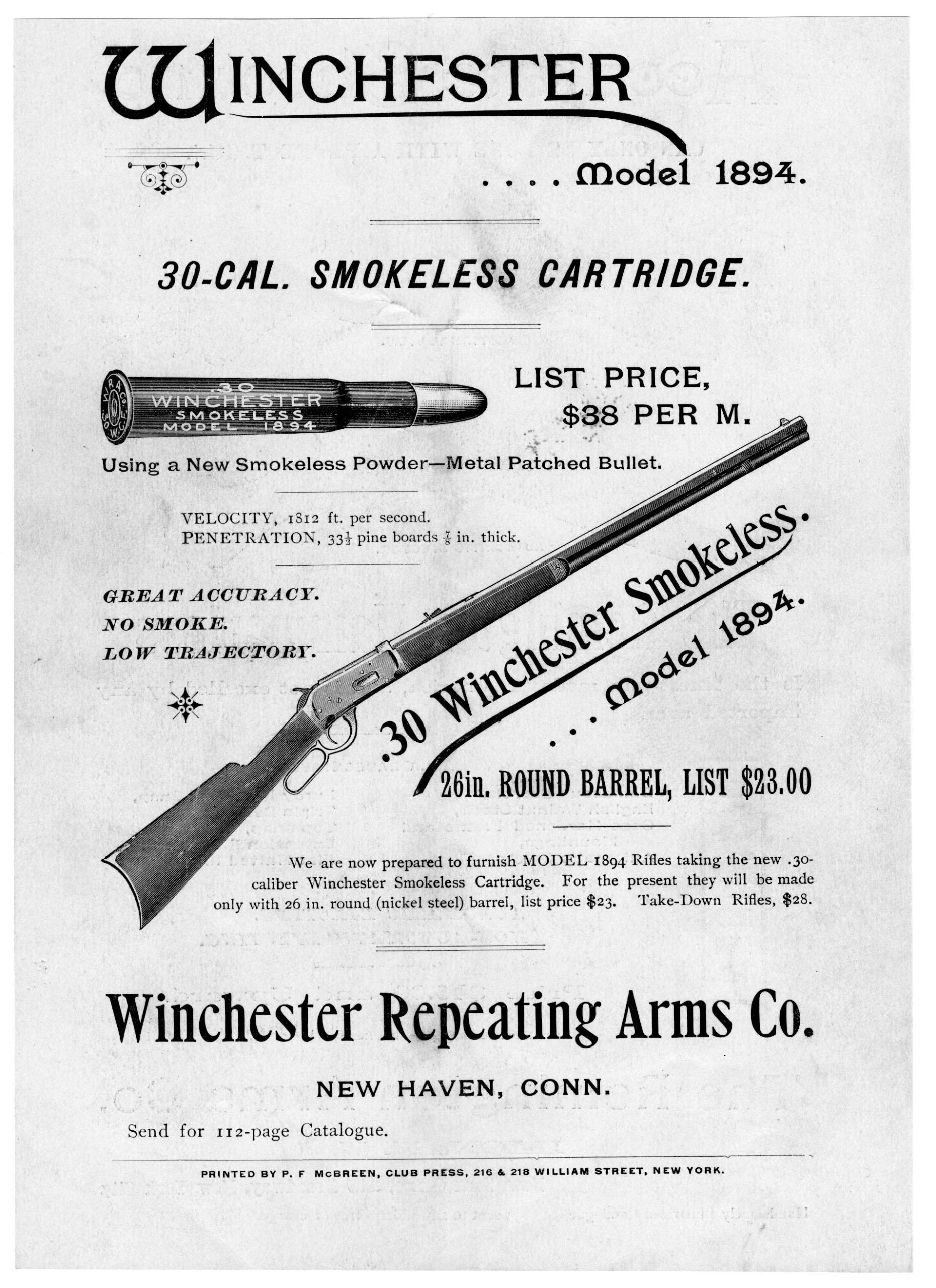

The original Model 94s were chambered to fire two metallic black-powder cartridges, the .32-40 Winchester and the .38-55 Winchester.

In 1895, Browning’s new lever gun became the first rifle chambered for a smokeless powder round. Since then, the Winchester 94 and the .30-30 cartridge have been practically synonymous.

The original .30-30 Winchester load featured a 160-grain bullet that cruised from the muzzle at around 2,000 fps toting more than 1,400 ft-lb of muzzle energy. While those numbers may seem paltry by modern standards, it was a giant leap forward compared to the black-powder loads of the day.

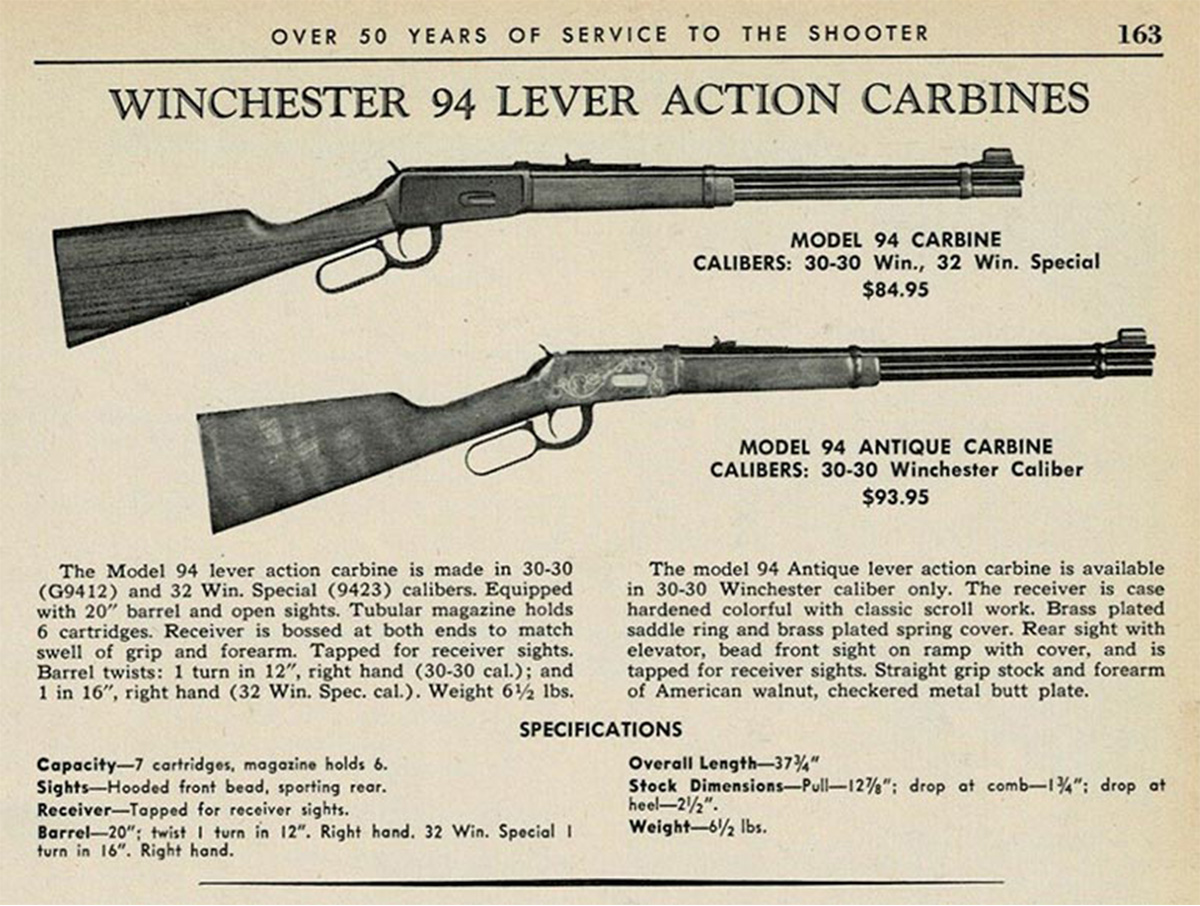

Back then, the venerable Winchester 94 lever action was available as a full-length rifle with a 26-inch barrel or a shorter carbine model with a 20-inch barrel. A shooter could pick up one for a mere $18. Today, a pre-1964 Model 94 in excellent condition can fetch a few thousand dollars.

Mine was definitely not in excellent condition.

But it worked, and that is one of the beautiful things about a lever gun — they can take some serious abuse and barely bat an eyelash. Even with all the rust, dust, and dents in my new-to-me rifle, it took only a little Rem Oil and some TLC to bring that dinosaur back to its prime.

RELATED — The Marlin 336 Is Back! Ruger Reintroduces a Classic Lever Gun

Winchester Model 94: More Than a Cowboy Gun

The Winchester Model 94 has made plenty of appearances on the silver screen. As a child, I had seen a healthy share of them on Sunday afternoon Westerns my dad religiously watched from his brown corduroy easy chair. It’s unfair that my exposure to the iconic lever action was limited to what I then considered cheesy cowboy shows, which made me seriously underrate the rifle’s potential in the deer woods.

Many sources claim the .30-30 Winchester Model 94 has dropped more whitetails than any other rifle. While it’s impossible to verify if this is truth or merely legend, it is highly probable that it’s accurate.

While .30-30 lever actions get smack-talked by hunters obsessed with speed and technology (my younger self included), anyone who questions its merits in the deer woods overlooks the hundreds of thousands of deer that have fallen to the rifle over the past 125 years.

More than 7.5 million Model 94 rifles rolled off Winchester’s assembly lines between 1894 and 2006 when production ceased. While saturation has undoubtedly contributed to the 94’s deer-dropping numbers, the gun’s deer-dropping proficiency definitely played a role in its popularity.

Few tools maintain their basic design for over a century and sustain consumer demand if they don’t freakin’ work.

GOOD GEAR — Solve Most of Your Morning Problems With The BRCC Coffee Saves Roast

The Winchester Model 94 Takes on the Deer Woods

I toted my Winchester Model 94 lever gun to the Virginia mountains that next season.

That top-eject lever action didn’t have the modern high-tech scope I’d hoped for, and Daddy didn’t want to drill into the stock to attach a sling mount, so he tied an old piece of rope around it to form a makeshift sling. I probably looked more like a hobo than a serious deer hunter.

But successful deer hunting isn’t about looks.

On the last day of the two-week season, our camp staged a quick man drive in a desperate, eleventh-hour attempt to fill tags. I Annie-Oakleyed the hell out of two beefy does that tried to zip past me, hell-bent on getting away from the man drivers hollering through the thick creek bottom they’d been holed up in. I whistled one quick note, and both deer stopped short at 70 yards, confused and looking for the source of the high-pitched tone.

I lined up the front sight with the crease of the bigger deer’s shoulder and pulled the trigger. That shot sent her somersaulting down the ridge, back toward the thick creek bottom she came from, a 150-grain soft point mushrooming through her boiler room.

The sound of the shot sent the second doe running headlong up the ridge behind me. I whistled again, but she wasn’t falling for it a second time. Cheek still down on the stock, I swung the rifle past her nose and squeezed the trigger as she tried to pass me in a full-out gallop.

I missed her completely on the first shot but managed to pull off a second that sent her sliding back down the ridge to settle just a few yards away from her buddy.

RELATED — 405 Winchester: T.R.’s Famous Medicine Gun for Lions

Falling in Love

I was a legend that year, the only one in deer camp to put meat on the pole. My dad bragged a blue streak at the checking station that evening, and my young cousin complained about how much he hated our hunt camp.

“Only girls kill deer here.”

And that is how I fell in love with lever guns.

Everything that makes the Winchester Model 1894 rifle perfect for chasing Eastern whitetails is found in the details of that story.

It is super easy to cycle, and with some practice, you can pull off follow-up shots without ever breaking your cheek weld (which comes in handy when the deer run by in pairs, particularly when it’s legal to shoot more than one).

The 94 is also a dependable, lightweight firearm that is easy to tote into rugged, thick woods, where deer like to hide, even if you don’t have a ratchet rope sling.

It also has a near-perfect, fast-handling balance. Its compact proportions and relatively short receiver make it easy to swing on targets moving through thick brush.

Although Model 94 lever action rifles are well-known for their mild recoil, one chambered in .30-30 Winchester has plenty of knockdown power to take out deer at the most common hunting ranges.

If you aren’t hunting the Wild West with miles of sweeping prairie, you probably won’t get a shot opportunity that stretches much farther than 100 yards. Most deer hunters sit overlooking a well-worn trail, food source, or field. None of those scenarios require you to shoot a deer standing in the next county over.

Rifles chambered in hyper-velocity cartridges capable of sniper-like accuracy, while admittedly sexy, are overkill for most deer hunters. The ballistics of hot-rod hunting cartridges may make the .30-30 look like a wimp in comparison, but only on paper.

A 150-grain soft point fired from a .30-30 Model 94 is still cruising along at 1,974 fps at 100 yards and carrying 1,298 ft-lb of energy, which is more than enough to drive a deadly mushroom ripping through a whitetail’s vital organs.

And while other cartridges may put up better numbers, the drawback to high-velocity, high-energy rounds is bloodshot meat. When that super-sexy speed demon hits a deer’s shoulder (or any other muscle, for that matter), the impact energy radiates through soft tissue, forcing coagulating blood into the meat you were hoping to serve up for dinner.

Wound channels from faster cartridges can tear up some meat. In comparison, the .30-30 produces minimal meat damage. With most shots, you can dine practically up to the bullet hole.

In an age where putting meat on a deer camp pole was far more important than posting big racks to Instagram, that was a huge measure of success.

That Winchester Model 94 .30-30 might not have been the shiny new semi-auto I wanted, but it was the rifle I needed, and it more than proved its worth as a deer-slaying machine. Putting deer on a deer camp meat pole is a practical measure of deer hunting success and one that definitely put some serious cowboy swagger in my step that year.

I’ve carried Grandpa’s 94 into the deer woods almost every season for the past 30 years, despite the fact that there are now newer, fancier, faster-shooting rifles in my safe. It’s put more venison in my freezer than anything else and continues to hold a special place in my heart.

READ NEXT — The Famous Winchester Model 1894 Was Born 127 Years Ago This Week

Comments