When the 38 Super cartridge came out more than 90 years ago, it had so much potential. It was made for the iconic 1911 handgun and delivered higher muzzle velocity than 9mm and more energy than .45 ACP. Now, you might be asking yourself: If it was so great, why haven’t I heard of it? And that’s a good question — it’s a great question, in fact.

Let’s figure out where the 38 Super came from, where it disappeared, and how it reemerged after 40 years to become a preferred cartridge for competitive shooters — for a little while, at least.

Cartridge History

Understanding this cartridge’s history can be confusing because of the wide range of .38-caliber cartridges released throughout the 20th century. Since the caliber was the most common for the handguns of the time, if you blink, you might miss something.

There are two camps of .38-caliber cartridges, beginning with the .38 Special and .38 ACP. While they differ in specification design and performance, the most obvious difference is that the former is a revolver cartridge and the latter is primarily a semi-automatic pistol cartridge.

The .38 ACP was introduced in 1900 by John Browning, the famed Mormon gunmaker, for use in a military pistol called the M1900. Then, Browning evolved the cartridge in 1908, with .380 ACP. It wasn’t so much of an improvement as an alteration. It used a shorter case, which meant less power, but it was meant for a smaller military handgun.

In the 21-year gap between 1908 and the year the caliber was released, Browning introduced his iconic 1911 pistol, which used the larger .45 ACP cartridge at the request of the U.S. military, and then he died in 1926. Three years later, Colt introduced the 38 Super as a chambering for the 1911.

Many argue that the obvious appeal of a 1911 in this chambering was magazine capacity. A standard mag held nine rounds instead of seven rounds of .45 ACP. And it delivered impressive ballistics. The caliber’s 130-grain bullet produced 70 foot-pounds more energy than a 230-grain .45-caliber bullet and was 35 feet per second faster than a 115-grain 9mm bullet.

To put that into perspective, famed gun writer Massad Ayoob explained that with that type of power, it could pierce car bodies and Prohibition-era “bulletproof vests,” but that was about it. He said it offered little “stopping power” as it “shot through human bodies like an ice pick.” He also said it was “flat-shooting, but notoriously inaccurate because it headspaced on its vestigial cartridge rim.”

As the story goes, the .38 Special evolved a few years later with the .357 Magnum, which, ballistically speaking, surpassed the 38 Super. That meant revolvers continued to dominate among civilians and law enforcement. After that, the cartridge took a bit of a hiatus and wouldn’t reemerge until four decades later.

According to Ayoob, the cartridge made a comeback in the 1970s after the company Bar Sto started making barrels “that headspaced on the case mouth, and the 38 Super’s superb inherent accuracy, at last, came to light.”

And then, in the early 1980s, the low-recoil, flat-shooting, and now accurate round became popular among competitive shooters in major events hosted by the United States Practical Shooting Association (USPSA) and International Practical Shooting Confederation (IPSC).

GOOD GEAR – Spartan Kick Your Tastebuds With the BRCC Ready To Drink 300, Vanilla Bomb

How Does the 38 Super Auto Stack Up?

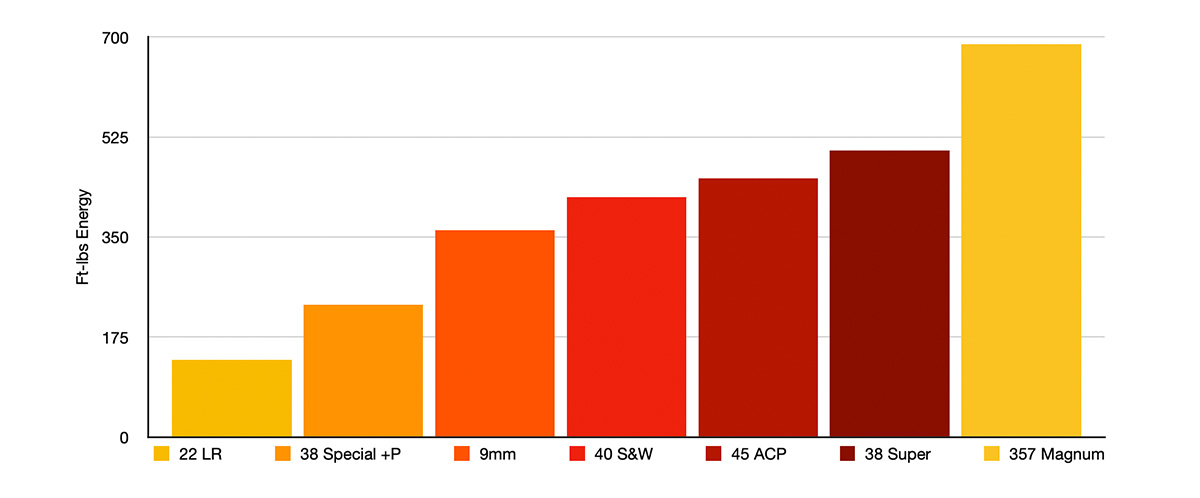

Compared to popular cartridges of today, the caliber really shines when you look at its muzzle energy. Launching a 115-grain bullet at 1,400 fps and a 124-grain bullet at 1,350 fps, the Super produces 500 ft-lb of energy, which is more energy than .45 ACP factory loads produce.

This difference in muzzle energy is less than 50 ft-lb on hot .45 loads, but worth noting. Alternatively, the government loading that made the .45 ACP famous as a man-stopper hit with 25% less energy than the Super. Muzzle energy aside, in similar-sized 1911 handguns, the 38 Super holds two additional cartridges in the magazine, offering another distinct advantage.

The recoil impulse of the 38 Super is very similar to the .45 ACP and not nearly as light as the 9mm. However, using a compensator makes the 38 a flat-shooting pistol that floats from target to target. A 38 Super 1911 with a compensator has dominated the IPSC competitions since the ’80s.

RELATED – Bushnell RXC-200 and RXU-200 Red Dots: 100-Round Test

Is the .38 Special the Same as the 38 Super?

Given that there are so many .38-caliber rounds, it’s only natural that people ask this. But when you compare 38 Super to the more common .38 Special, you’ll find they have virtually nothing in common.

The .38 Special and the 38 Super are not only dimensionally different but also vastly different in performance. The .38 Special was designed to be a revolver cartridge with a larger rim diameter than the 38 Super, which was designed for autoloading pistols. Neither cartridges are interchangeable in any way.

Although shorter in overall length and case capacity, the 38 Super shoots the same weight bullet approximately 200 fps faster than the hottest +P .38 Special loading. This is a significant performance and bullet energy increase over the .38 Special.

Compared to the .38 Special and .357 Magnum, the 38 Super falls directly between them in terms of power. It poses a significant advantage over the .38 Special but doesn’t compare to the legendary .357 Magnum. The distinct advantage that the middle-child cartridge has over these two is the ability to be loaded into a semi-auto handgun. The increased capacity can’t be overlooked. The Super Auto holds an additional four rounds over the standard six-shooter.

GOOD GEAR – Embody the Ethos of the Quiet Professional With the BRCC Silencer Smooth Roast

How Similar Are the 38 Super and 9mm?

Since both the 38 Super and the 9mm were designed to be self-defense rounds for autoloading pistols and shooting similar-weight bullets, it is easy to compare the two directly.

The 38 Super is more powerful than the 9mm. The 38 Super offers a 100 fps to 150 fps velocity advantage using the same bullets over the vulnerable 9mm. Both the .38 ACP and 9mm were developed around the same time frame. Although, as previously mentioned, the 38 Super originated at lower pressures than it is today, the original loading was very similar to the 9mm.

The bullet diameters are the same in both cartridges, lending to this being an easy direct comparison. With the same bullet weights, the 38 Super is always faster and will always produce more energy. With a 115-grain bullet, the 9mm produces 366 ft-lb of energy, compared to the 38 Super’s 500 ft-lb.

Where the 9mm has the advantage is simply cost and availability. When it can be found, the 38 Super costs between $0.80 and $1.44 per round. Compare that to the widely available 9mm, which can be had for $0.28 per round, and the difference becomes clear.

Ammunition costs aside, far more handgun options are available for the 9mm. There are endless handgun models and sizes on the market for the 9mm, while the 38 Super can pretty much be had in only one flavor — 1911.

Will the Caliber Escape Obsolescence?

The cartridge was introduced at a time when revolvers dominated the handgun market, so manufacturers had little interest in maximizing the pistol cartridge’s performance. But that attitude has arguably flipped, and today, the people want pistols.

With that said, there’s no shortage of factory ammo options or handguns for this cartridge today. And, while there are a variety of manufacturers making 38 Super pistols, they’re mostly 1911s. In fact, Tanfoglio is the only company making alternatives. While this is hardly enough evidence to say that the 38 Super will stick around forever, it’s enough to say it’s here for now.

READ NEXT – Why People Love or Hate the 1911 Pistol

Comments