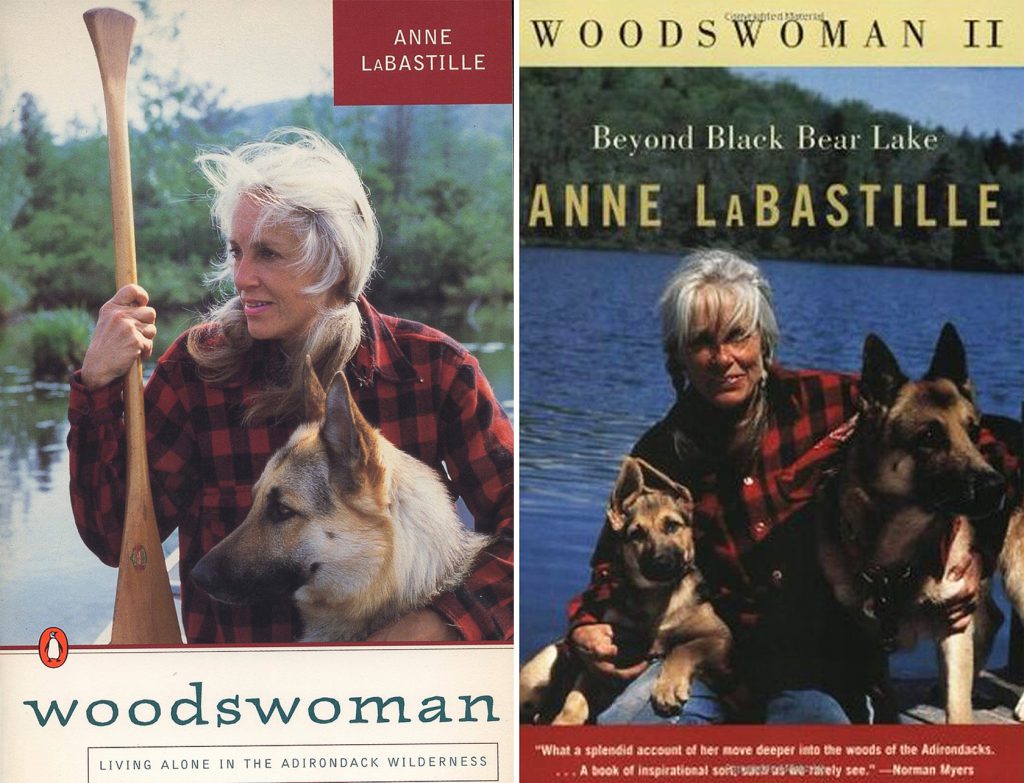

As far as writers go, you don’t find many routinely perched in a canoe floating in the middle of a lake with a typewriter balanced on their knees and a German Shepherd perched at the other end of the boat, but that’s how you were likely to find Anne LaBastille on most days with good weather.

That image of Bastille keeping everything in carefully maintained equilibrium while writing and serenely floating on the lake by her isolated cabin home nicely symbolizes the two lives she led, including the life in nature that she chose for herself.

She was a fierce conservationist, a homegrown woodswoman, a self-made writer, and an environmental steward who lived alone in a 12 x 12 cabin in the Adirondacks that she built with her own two hands (and the help of a few local loggers and friends). Anne was full of grit and moxie; she was fierce and determined; she was an Adirondack rockstar.

But Anne didn’t escape to the woods to flee society. She wasn’t ill-prepared like Christopher McCandless or antisocial like Christopher Knight. She had plenty of friends and welcomed many visitors during the decades she lived in her cabin alongside Twitchell Lake.

Anne simply traded the hustle and bustle of city life for the purposeful solitude of living mostly alone — she had her German Shepherds for companionship and protection — while immersing herself in nature. She became self-reliant in a way most people never even try to be, and she documented it all in over 150 magazine articles, more than two dozen scientific papers, and 16 books.

“It’s hardly an exaggeration to call Anne the Carl Sagan of conservation,” James Lassoie, a professor of conservation at Cornell University and longtime colleague of LaBastille, told the Adirondack Explorer. “To many, she embodied the Adirondacks because she was able to communicate a feeling of concern and ownership to countless readers worldwide.”

RELATED: Oliver Winchester and Sam Colt – Innovators and Lousy Gunmakers

Humble Beginnings

Born in 1933, Anne progressed from a traditional childhood in Montclair, New Jersey, to a marriage that took her to the woods. She married C.V. “Major” Bowes who was 15 years her senior. They did not have any children during their 7-year marriage. Instead, the duo worked at his backwoods resort: the Covewood Lodge on Big Moose Lake in New York.

While she learned a lot, she also rarely got time off as she filled numerous roles as caretaker, hiking guide, and stablehand since she and Major were often the lodge’s only employees. On her few weekends off, she escaped to the woods alone, often with an old sleeping bag that wasn’t quite warm enough and a few granola bars stuffed in her pockets.

“After spending several years married to an Adirondack innkeeper, with the hustle, bustle, and strain of managing summer guests, staff, eight cottages, a dining room, fourteen fireplaces, a dozen hotel rooms, horses, boats, salesmen, chefs, and bakers, I viewed moving into my tiny cabin with mixed fear and anticipation,” Anne writes in Woodswoman: Living Alone in the Adirondack Wilderness. “It would be a tremendous change in lifestyle, albeit a therapeutic one.”

RELATED: Smith and Wesson Founded Their Gun Company 165 Years Ago, Not 169

After she and Bowes divorced, LaBastille moved to the woods permanently. She purchased a narrow parcel of land along Twitchell Lake in Big Moose, New York, that was sandwiched between two privately-held 50-acre plots and built her 12 x 12 log cabin that was heated solely by a fat Franklin wood-burning stove. It had no plumbing or electricity.

It was there that she began her long career, which included her popular series of Woodswoman books and articles for National Geographic magazine, Sierra Club, and other publications.

“I wanted tranquility and to be close to the wellspring of life,” Anne told The New York Times in 1977.

She earned her Ph.D. in Wildlife Ecology from Cornell University in 1969 and soon became a female pioneer in environmental and conservation issues that spanned both her local roots (acid rain in the Adirondacks) and personal passions (tracking down the last of the great grebes of Atitlán).

LaBastille was the first female National Audubon Society tour guide where she refused to bow to traditional dress codes, saying “skirts got in the way” She also became the first member of the Adirondack Park Agency Board of Commissioners with a scientific background.

She served as a commissioner from 1975 to 1993 and became one of the only female licensed New York State Guides in the 1970s providing guide services to backpackers and canoers on and near the lakes and streams within the 6-million-acre Adirondack Park.

RELATED: Annie Oakley – A Legend Who Taught Thousands of Women to Shoot

“Being a woman in a man’s world was hard for her, to say the least,” Doris Herwig, a close friend of LaBastille’s for more than 50 years and operator of Hayfield Tours in Queensbury, told the Adirondack Explorer. “She was strong, determined, knew her stuff, and was also thick-skinned. When she put her mind to something and wanted it, you better move aside. Her tenacity was remarkable.”

A tireless advocate for nature, the outdoors, and wildlife, she created a natural wildlife reserve along Lake Atitlán in Guatemala to protect the giant grebes, earning a World Wildlife Fund gold medal for her work in 1974.

Even though it was difficult to leave her beloved cabin behind, she often trekked to places around the world, trading her Adirondack serenity to work with nonprofits on wildlife and conservation issues that impacted water quality and wildlife habitat preservation.

A Lasting Legacy

Today, Anne LaBastille is still revered for her passions and pursuits, despite passing away at the age of 75 in 2011. Best known for her Woodswoman books (a four-book series), she leaves behind her depth of knowledge chronicled through thousands of well-crafted stories that almost weave a myth about who she was and why her desire to live off the land alone as a woman in the 1960s is both admirable and glass-ceiling shattering.

She continued to live in her cabin until she was in her 70s, continually inspired by nature and acting as a steward to the lands, waters, and wildlife that do not have their own voices.

RELATED: Sitting Bull Has Great-Grandson in South Dakota, DNA Test Confirms

“Older women have the experience and maturity to offer the greatest service and skills to society of any segment of our population,” writes Anne in Woodswoman III. “They are at the peak of their promise…Since we are the natural caretakers in this world, I feel the greatest good that women can do is help the environmental movement.”

In 2015, four years after LaBastille’s death, her remote cabin was carefully dismantled and relocated to the Adirondack Museum in Blue Mountain Lake, New York, where it was reassembled for future generations to visit so they can learn about this woman of the woods.

Read Next: Hiram Maxim – The Right Place, Right Time, Right Gun to Change History

Comments