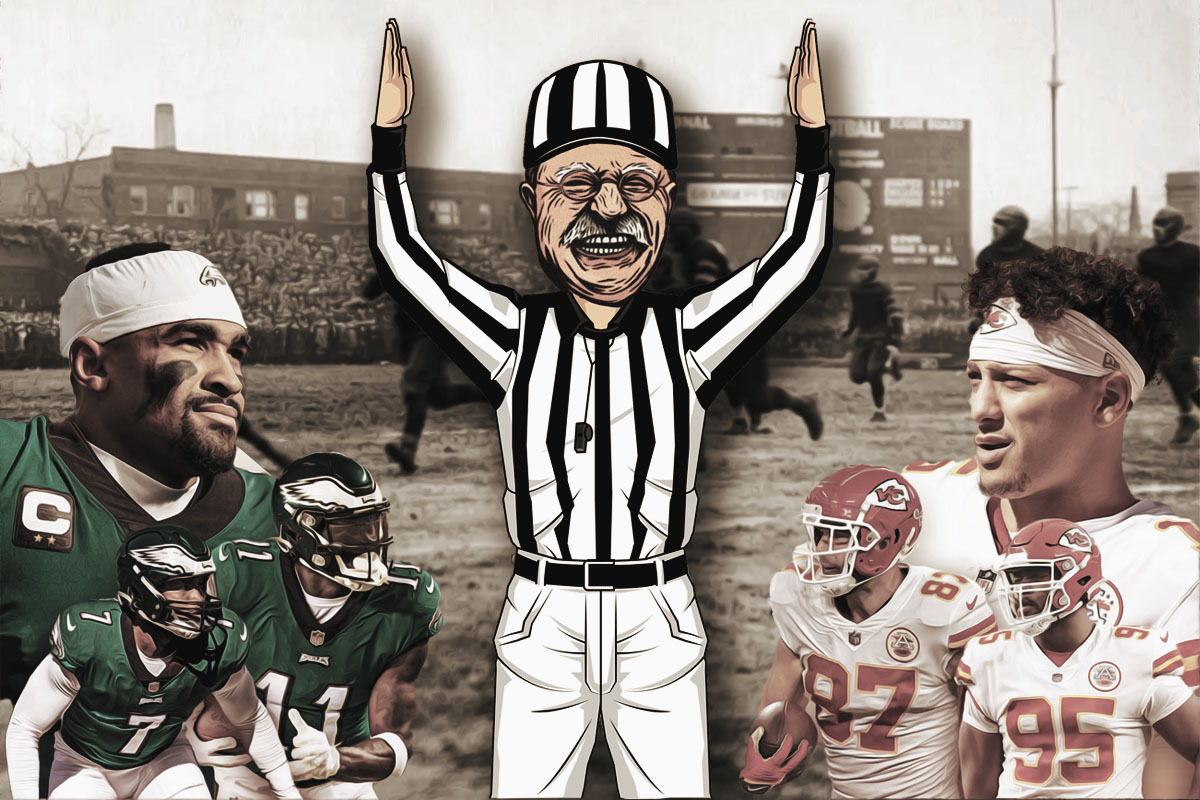

Teddy Roosevelt: 26th president, legendary hunter and conservationist, overall badass, and — the reason we have the NFL as we know it? Believe it or not, among his many accomplishments and badass undertakings, Roosevelt helped shape the history of American football. We have T.R. to thank for Friday night lights, killer college game-day tailgates, and bitchin’ beer-drenched Super Bowl parties.

In T.R.’s day, football was so grinding, dangerous, and chaotic that colleges and critics called for an outright ban because too many players were getting mangled and killed on the field. Thankfully, Roosevelt stepped in to save football from itself without sissifying the sport. Here’s how he did it.

The History of American Football

Invented in the 19th century, the sport of football we know in the United States, like America itself, was born from a melting pot. The history of American football has roots in both rugby and soccer, pulling together the best aspects of both sports and rolling them with healthy doses of violence and determination to create something originally American.

The first official college football game was played on Nov. 6, 1869, between teams from Rutgers and Princeton universities, and it looked nothing like the games people screamed through while partying their way through college.

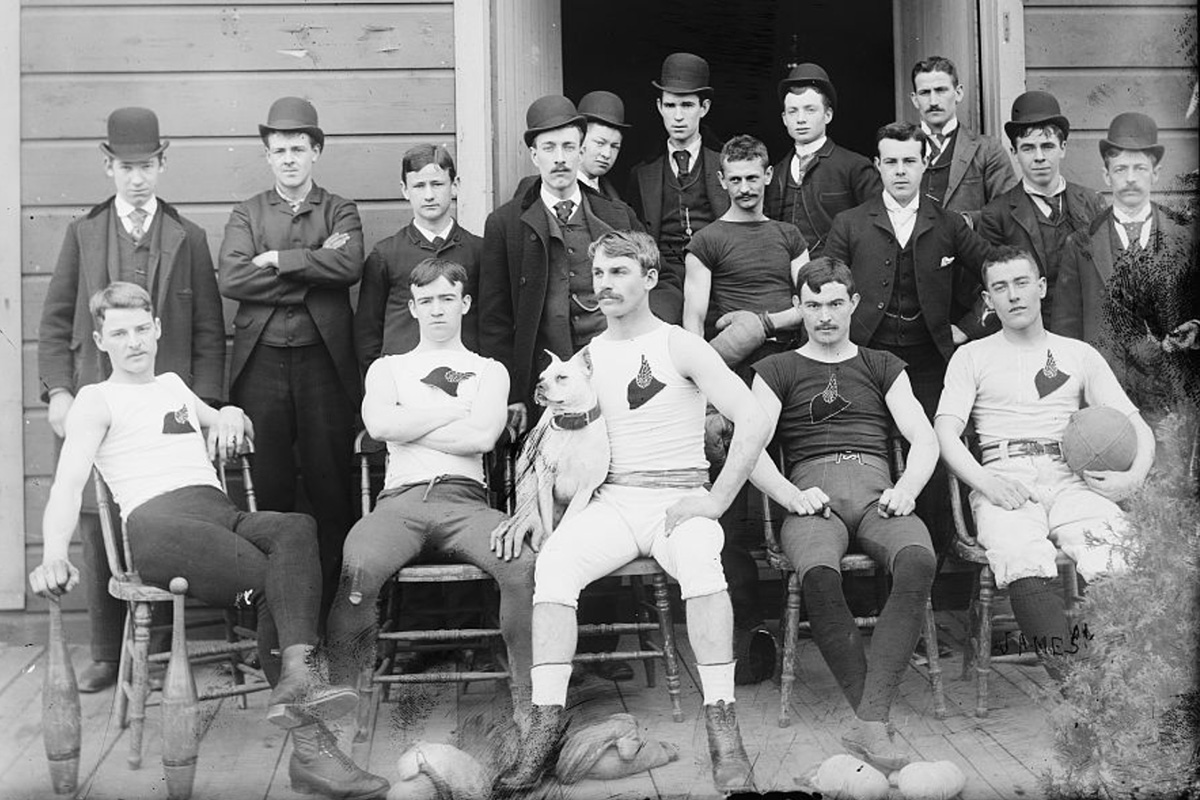

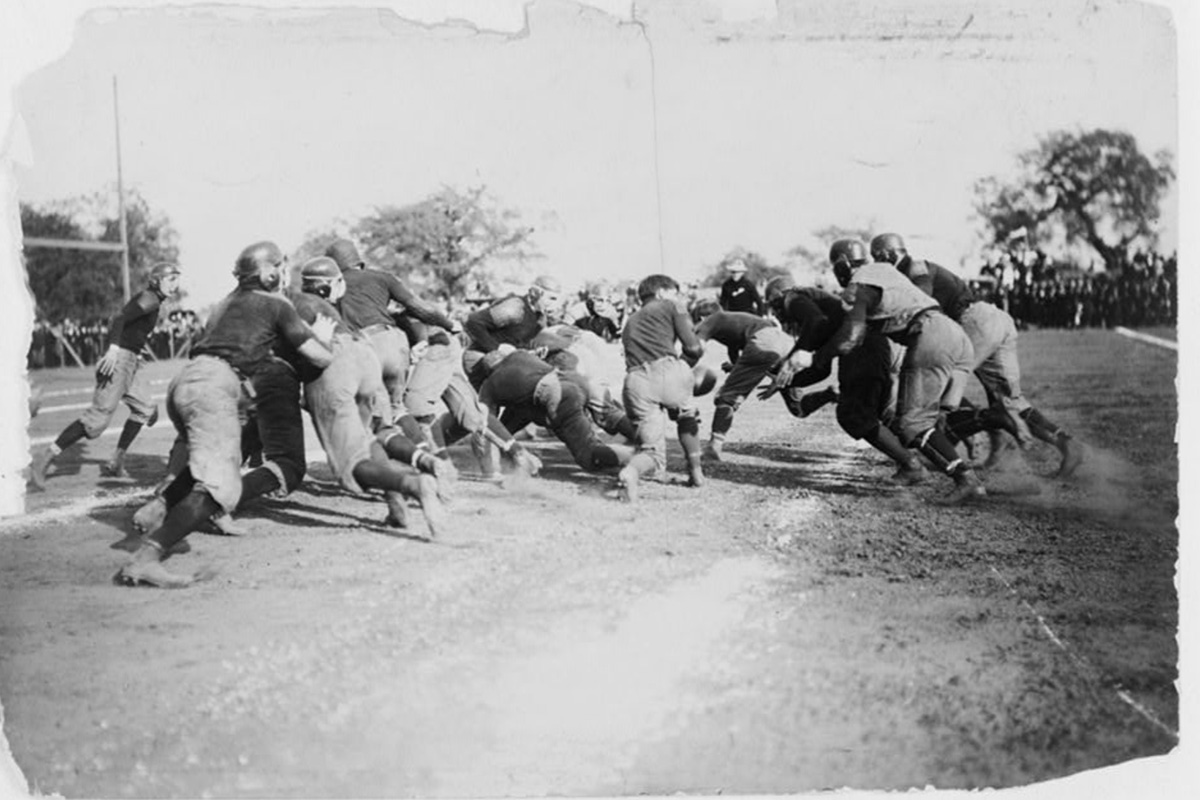

The earliest football games resembled 22-man cage fights, only far more brutal and with way fewer rules than the UFC Octagon. Games were a free-for-all, anything-goes scramble to score; blood, concussions, broken bones, and internal injuries were a regular part of the game.

Modern American football is still laced with danger, as is evidenced by 24-year-old Buffalo Bills safety Damar Hamlin’s recent on-field heart attack and all the controversy surrounding football-related TBIs. However, by the standards of Roosevelt’s time, present-day pigskin scuffles look more like Zumba class at an old folks’ home.

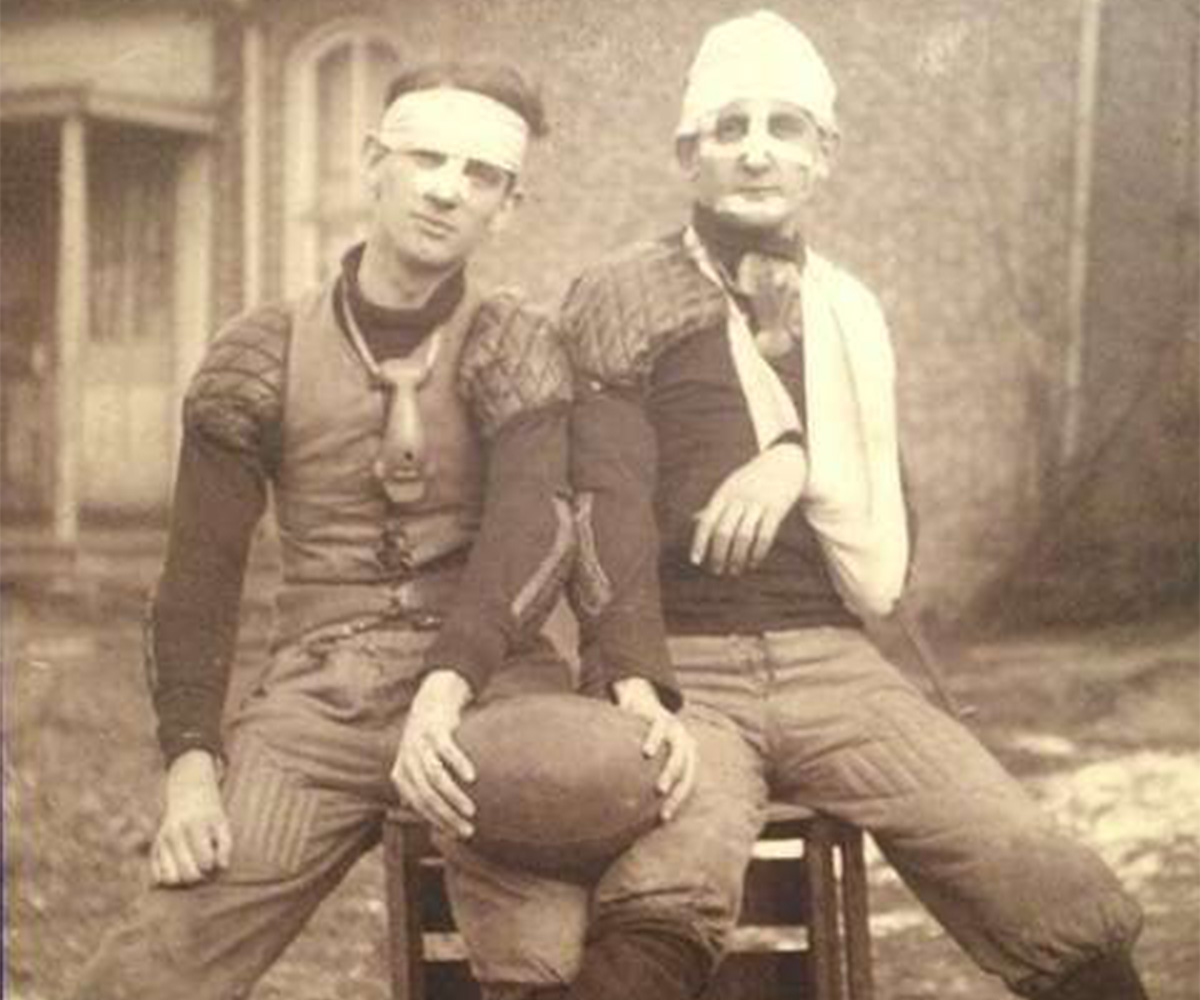

During the 1905 football season, 19 players died, and another 137 were seriously injured. Punching and dropkicking were perfectly legal, and protective gear was practically nonexistent (think optional flimsy leather swim caps). Football became famous not for scantily clad cheerleaders or super-rad tailgating but for habitually killing and maiming college students.

The Chicago Tribune even labeled the sport a “death harvest,” and the Cincinnati Commercial Tribune ran a political cartoon featuring the Grim Reaper perched on a goalpost overlooking the twisted carnage on the field.

In addition to the inherent risk of death and bodily injury, the game was also plagued by corrupt referees and recruiting scandals that make Deflategate seem petty, pure, and honest in comparison.

GOOD GEAR – Enjoy This Month’s BRCC ECS Coffee Release When You Sign Up Today!

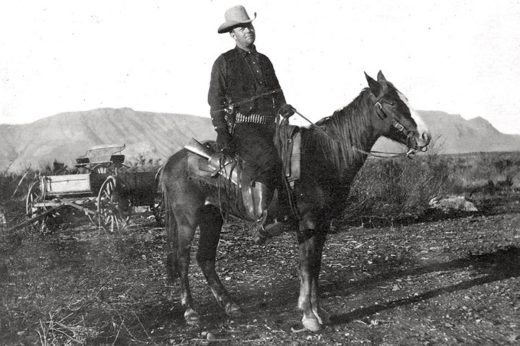

Skin in the Game

At the time, President Roosevelt was a passionate fan of the sport but also had plenty of skin in the game. All four of his sons — Ted, Kermit, Archie, and Quentin — played ball at the exclusive Groton School in Massachusetts.

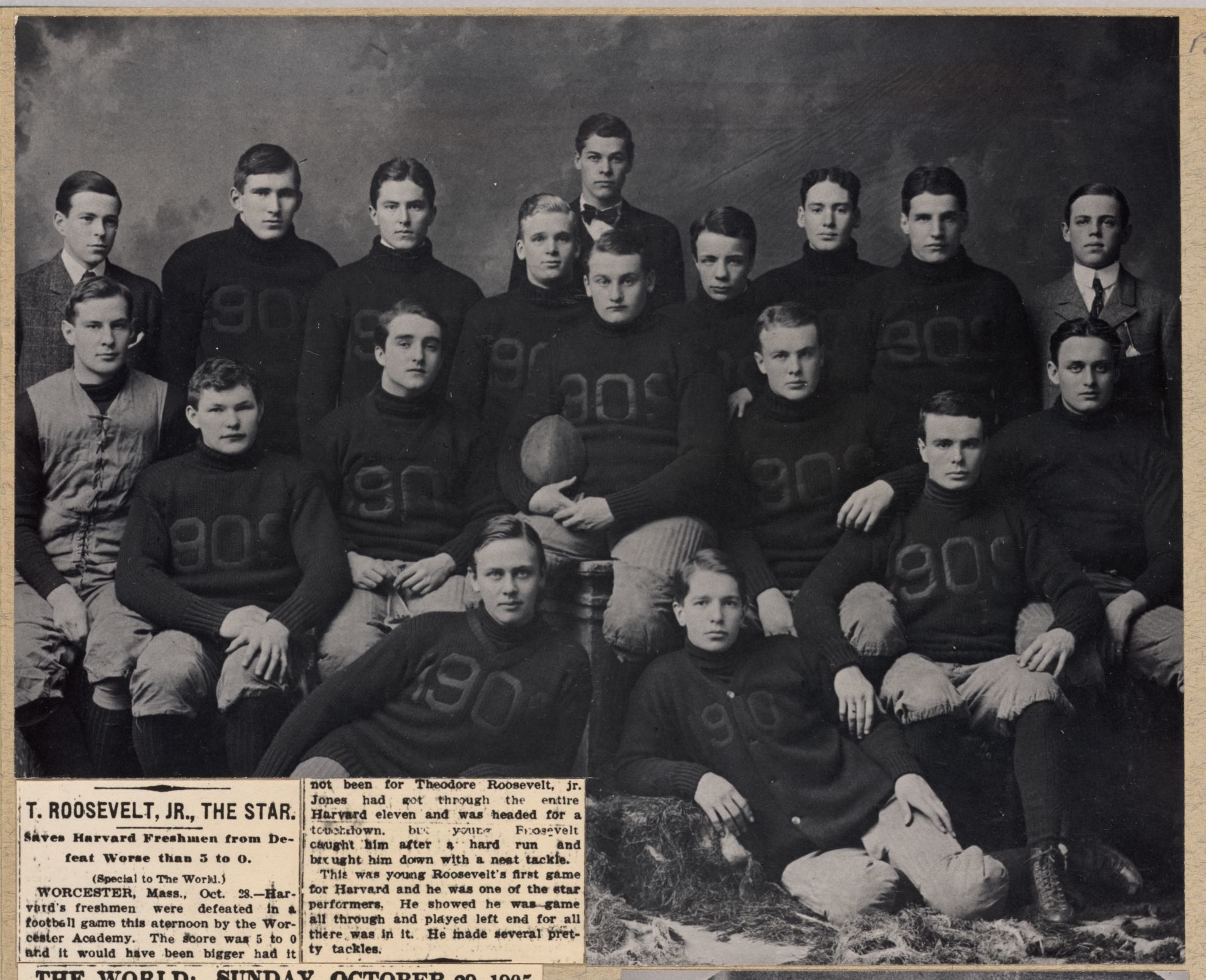

The prep school gridiron had not been kind to Roosevelt’s oldest son Ted. While playing for Groton, he racked up a broken nose and collarbone and badly damaged teeth. Despite the injuries, Ted decided to give Harvard football the old college try, fielding as a freshman in 1905.

Standing just 5 feet, 7 inches and weighing about 145 pounds, the younger Ted wasn’t built like the stereotypical football players of today. He was small and received a severe smackdown playing tight end during the Harvard-Yale freshman game.

The younger Roosevelt told his father in a letter home that he was “just shaken up and bruised.” However, he was knocked unconscious twice during the game and ultimately had to be carried off the field with a neck injury, a black eye, and a nose so thoroughly smashed it required surgery.

A week after young Ted’s injury, the Harvard varsity football team almost walked off the field after an illegal hit from a Yale player on a fair catch rolled their captain. The slam broke the Harvard player’s nose, leaving him covered in blood.

The same afternoon, Union College halfback Harold Moore was kicked in the head during a tackle attempt on a New York University runner. He died later that day at the hospital from a cerebral hemorrhage.

RELATED — Roosevelt’s Rough Riders Era Custom S&W Sells for $910K

Football’s Near-Death Experience

Public outcry reached a fever pitch as college football was basically a bloodbath of brutality. Newspapers openly criticized the collegiate carnage and called for an outright ban. In 1906, Columbia, Duke, and Northwestern dropped football altogether, and Stanford and California switched to the gentler sport of rugby.

Harvard president Charles Eliot warned that Harvard would be next, calling the sport “more brutalizing than prizefighting, cockfighting, or bullfighting.”

Despite collegiate football’s death toll, the harsh opinions of public media, and his son’s gridiron thrashing, Roosevelt loved the rough nature of the game.

“I believe in outdoor games, and I do not mind in the least that they are rough games or that those who take part in them are occasionally injured,” he remarked at a Harvard alumni dinner in June 1905.

RELATED — Teddy Roosevelt Ran a Suppressor on Three of His Hunting Rifles

Roosevelt Steps In

Eliot’s threat was the final straw for the Harvard alum occupying the White House. He scratched off a letter to a friend vowing not to let the Ivy League president “emasculate football.” Roosevelt also expressed a desire to “minimize the danger” without gameplay being reduced to “ladylike” behavior.

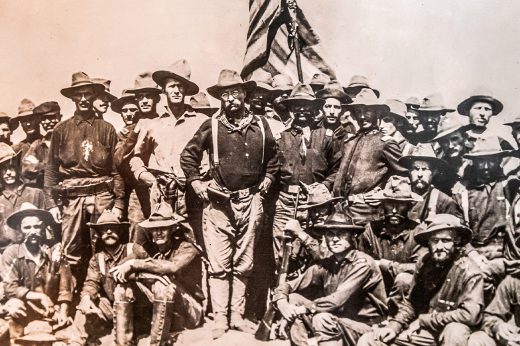

Old Rough and Ready Roosevelt set out to save American football and the manly nature of the sport. In October 1905, “Big Stick” Teddy called the collegiate football powers from Harvard, Yale, and Princeton to the White House and strongly encouraged them to play fair and tone down the on-field savagery. The meeting included Walter Camp and John Owsley of Yale, Bill Reid and Edward Nichols of Harvard, and John Fine and Arthur Hildebrand of Princeton.

“Football is on trial,” T.R. said to begin the meeting. “Because I believe in the game, I want to do all I can to save it. Thus, I have called you all down here to see whether you will not all agree to abide by both the letter and spirit of the rules, for that will help.”

During the meeting, Roosevelt also called out all three schools, providing specific examples of their unsportsmanlike conduct, including coaches pressing players to commit fouls while the refs weren’t looking.

At the meeting’s conclusion, T.R. ordered the attendees to work together to end mucked-up play and respect existing rules. The men drew up an agreement on the train ride home, and the schools released a statement denouncing gratuitous violence and pledging cleaner pigskin play.

A few months later, on Jan. 6, 1906, representatives of 62 colleges and universities met in New York City to approve major rule changes for intercollegiate football competition. Designed to make the sport at least slightly less deadly, the contributing colleges implemented a ban on body-breaking mass formations, the legalization of the forward pass, and the introduction of a fourth official to enforce the rules.

The newly established rules committee formalized its mission in March 1906, and the Intercollegiate Athletic Association (now the NCAA) was officially born.

RELATED — Roosevelt’s Legendary Double Rifle, the ‘Big Stick,’ up Close

The History of American Football Lives On

America held its breath as the 1906 football season approached, hoping to see a somewhat safer, although far from gentle, version of its favorite contact sport. That year saw a meager shrinkage in fatalities, logging only 11 football-related deaths and a decline in serious injuries. That number would hold steady the following year.

Major credit for the slight increase in safety was given to the new rules, and gridiron football survived to become the uber-popular, kickass sport that fills everything from small-town bleachers to massive stadiums across the country every fall.

While you’re saucing up your hot wings, donning team jerseys, and slathering on face paint for Super Bowl Sunday, pause to raise a toast to Teddy for saving the rambunctious, collision-packed, organized mayhem called American football.

If it weren’t for T.R., the history of American football would have been a whole lot shorter, and we’d probably be spending our fall and winter Sundays, Monday nights, and most Thursdays watching rugby — or, worse yet — soccer.

READ NEXT — Why Theodore Roosevelt Was the Most Badass President Ever

Comments