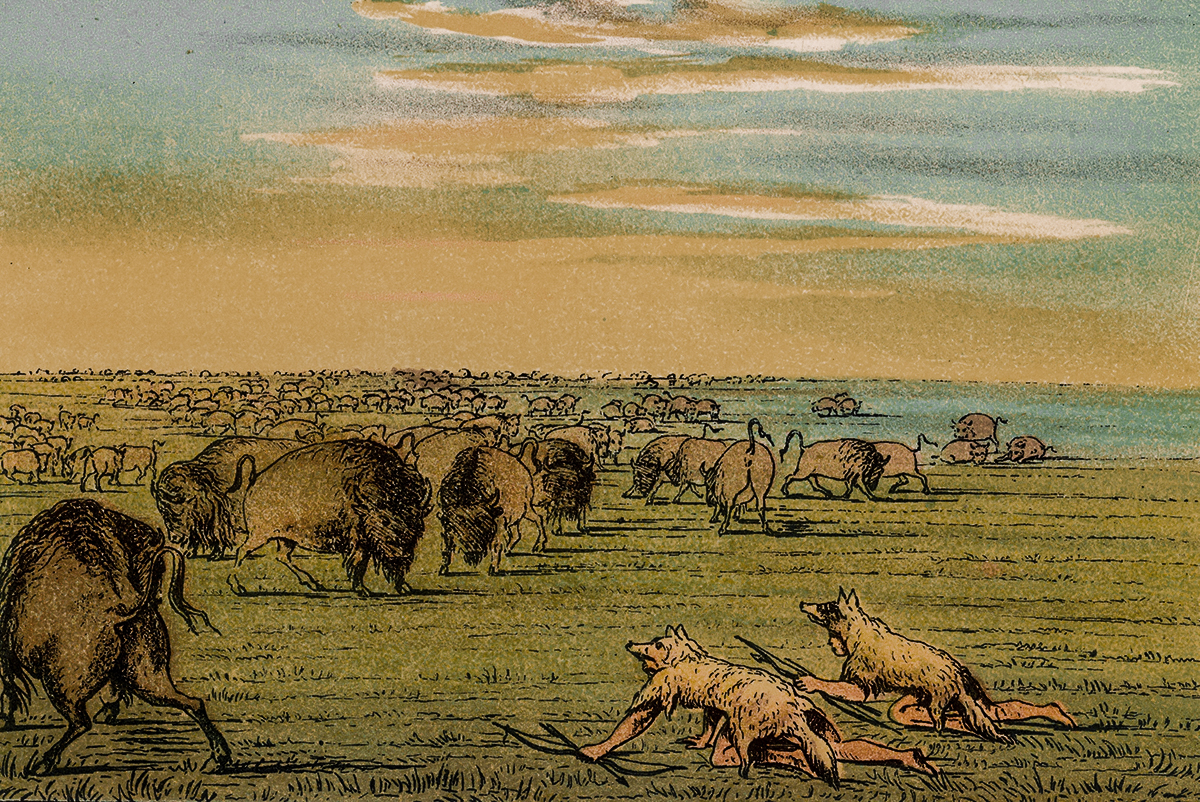

Humans did not invent camouflage patterns. We discovered the concept like we discovered fire — we observed what nature does and replicated it to serve our purposes. Toads look like rocks, stick bugs look like sticks, and chameleons look like all kinds of stuff. Leopards have spots to hide in the shadows (animals don’t see the orange behind the spots the way we do), and zebras have stripes to hide in a crowd.

Hunting is a high-stakes game of hide-and-seek, and to win, early humans likely took inspiration from the animal kingdom. From prehistoric times to today, here’s a brief history of camouflage and how humans have used it for hunting.

Prehistoric times to the 1800s — The Earliest Days of Hunting Camo

According to Ancient Origins, humans have covered themselves with skins, oils, and animal scents to stalk closer to prey for more than 150,000 years. That means you go back to the year 0 and then keep going back another 148,000 years or so.

Anthropologists think this was inspired by observing insects and animals that could alter their appearances to blend into their surroundings. Hunter-gatherer tribespeople all over the world concealed their relatively monochromatic skin with body paint and elaborate dress, usually made from the skins of the animals they were emulating. It all manipulated shadow and form similarly to how modern camo works.

Camouflage works by breaking up shapes and colors that the eye of another predator or prey associates with danger. It’s amazing how easily a human face stands out amid the green verdant forest or jungle, but if you paint the nose and chin and break up the forehead and cheeks with patterns, all of a sudden, the brain behind a pair of eyes will skip right over it.

Then, for the most part, we got civilized. The more humans farmed, the less we relied on hunting — and camouflage. Most of us didn’t even use camo on the battlefield until smokeless powder came along. On the contrary, it was important to see the brightly colored uniform of friend or foe amid the smoke of cannons and muskets.

But in the late 1800s, with repeating rifles and the advent of smokeless gunpowder, soldiers started smearing mud on their uniforms to hide better. Though not connected, Scottish gamekeepers picked up camouflage hunting clothes around the same time. The age of camouflage was coming.

RELATED – New KUIU Encounter Collection Is Engineered for the Treestand

The 1800s — The Ghillies and Their Suits

The ghillie suit, made famous by snipers, was originally worn by Scottish hunting guides and land managers called ghillies. Ghillies were responsible for showing lords, ladies, and guests around the wilderness on large Scottish estates.

In parts of Scotland, ghillies still exist, and they are expert woodsmen. They’ve always understood the need to break up one’s outline when stalking game and made a suit specifically for the task. It’s sewn together with netting, burlap, and vegetation, and it looks like a pile of seaweed washed up on the beach.

Ghillies would wear these suits as portable hunting blinds. They’d sneak up on game for various purposes and sometimes even capture live animals to use in canned hunts for lazy aristocrats. The ghillies brought ghillie suits to the Boer War, and the British would go on to use them during World War I.

Today, they have become one of the most famous and infamous pieces of gear used by modern snipers. Hunters are also rediscovering them, but we’ll get back to that.

RELATED – Bowhunting for Beginners: Fred Eichler’s Gear Breakdown

1914 to the 1950s — Artists, Armies, and Duck Hunting Camo

In 1914, with the start of World War I, camouflage got its name. The French employed hundreds of artists, called camofluers, to paint equipment, conceal snipers, and deceive the enemy. The painters were influenced greatly by cubism, and they created elaborate patterns to manipulate light and shadow. One of the more remarkable patterns of The Great War was dazzle camouflage for ships.

Dazzle camo was a family of complex patterns using geometric shapes in contrasting colors that interrupted and intersected each other at odd angles. The design wasn’t meant to conceal but rather to make it difficult for the enemy to estimate a target’s range, speed, and heading. It was used throughout the war and into WWII and beyond.

When WWII popped off, the need for good camouflage became dire. In the European Theatre, while the German army readily adopted various camo patterns, the Allies were slower to pick up the concept, relying on drab khaki and solid green for most of the war.

But the bloody, close-quarters jungle warfare of the Pacific Theater prompted Americans to find ways to hide their soldiers. They landed on a pattern called M1942 “Frog Skin,” designed by Norvell Gillespie, the gardening editor for Better Homes and Gardens.

The Marines issued a reversible Frog Skin outfit to their men. However, the pattern stood out in the dark jungle, so they shelved most of their 150,000 uniforms. After the war, with crates of unused Frog Skin camo in warehouses, enterprising civilians marketed it to duck hunters.

When the surplus dried up, clothing companies started making new Frog Skin camo duck-hunting gear to satisfy demand. The pattern picked up a new name: “duck hunter” camo. That name is still used today.

Interestingly enough, early Vietnam War advisors, special forces, and Bay of Pigs Invasion participants bought civilian duck hunter camo clothes to wear overseas.

RELATED – Saddle Hunting and Hunting Saddles: A No BS Beginner’s Guide

1960 to 1970s — A Hunter’s Shield of Safety

The next big change to hunting clothing has more to do with being seen than with hunting camo. In postwar America, hunters hit the woods in droves. Unfortunately, in the era before hunter safety was a thing, increased numbers of hunters also caused an uptick in hunting accidents. State agencies and outdoor leaders looking for ways to keep hunters safe began experimenting with different brightly colored garments while mandating hunter safety classes.

In 1960, Frank Woolner wrote an article for Field & Stream entitled “Hunter Orange—Your Shield of Safety.” It references a U.S. Army study that found blaze orange stands out to the human eye. He described the color as an “almost painfully brilliant daylight fluorescent.” One year later, Massachusetts adopted a law requiring hunters to wear blaze orange in the woods, and many states followed suit.

At the same time, waterfowlers continued to wear commercial duck-hunter camo and surplus military clothing. (Birds, including turkeys, can spot blaze orange better than deer.)

On the military side, combat uniforms remained olive green, though special forces and other units were issued tiger stripe camo for the first time. It was effective for special operations, but the uniforms didn’t stand up to the punishment grunts put them through — the camo ink would be bleached out by the sun and constant humidity.

The 1980s to 1990s — Hunting Camo Takes Off

In 1980, a hunter and entrepreneur named Jim Crumley ran an ad in Bowhunter Magazine that said, “TREBARK CAMOUFLAGE IS COMING.” Bowhunters were always more concerned with camo because they had to get closer to game than their rifle-hunting buddies. Also, many bowhunters didn’t have the benefit of brush on the ground for cover or a blind when they were up in a treestand.

Crumley had been experimenting with camouflage since the late 1970s and finally hit on something. Blaze orange didn’t work for bowhunters (and most state laws didn’t require it because of the relatively short range of archery tackle). Crumley was dissatisfied with military surplus camo patterns and the duck hunter camo of the day.

He felt those patterns blended into the whole woods, but he wanted to blend into the object most bowhunters stand against when they hunt — a tree trunk.

He set to work on some drab Dickies clothing as a base with odorless permanent markers, mimicking bark patterns. The pattern he made ended up being the first camouflage pattern specifically designed for hunters. In 1983, Cabelas advertised Trebark Camo in its catalog, and demand for the clothing skyrocketed.

By the mid-to-late-1980s, hunter-specific camo companies had sprung up all over the place. Toxy Hass with Mossy Oak, Bill Jordan with Realtree, and Jim Barnhart and Stan Starr Jr. with ASAT all promised they could hide hunters better than the next guy. A race to create more realistic camo patterns continued into the late 1990s.

RELATED – Chuck Adams and Remi Warren on Fred Bear’s 10 Commandments of Hunting

2000 to 2010s — Science-Based Patterns vs. Photorealism

By the early 2000s, photorealistic camo patterns were all over the woods, and old heads were left to grumble about it as they strode into the deer woods wearing their old jeans and red duck jackets. A sort of camo pattern one-upping game got rolling due partly to licensing deals between major camo designers like Realtree and Mossy Oak and clothing manufacturers.

At the same time, with the Global War on Terror ramping up, the U.S. military reevaluated the woodland and desert camo patterns they’d been using since the early 1980s.

The military moved into the digital pattern era with the Army’s bluish ACU pattern. The pattern was intended to work as a universal camouflage pattern but actually didn’t work well everywhere, especially after it had been faded by the desert sun.

The Marines also moved to “pixelated” digital camo patterns — the Marines even had different patterns for different environments — and the Navy used a weird blue-heavy pixelated camo pattern for a while.

In 2006, two hunters named Jonathan Hart and Jason Hairston set out to shake up the world of hunting clothes. Their designs were different. Both men were sheep hunters who hunted in high-tech mountaineering fabrics. However, their climbing clothes that were so well suited to the mountains were too brightly colored for hunting. Hart and Hairston tried to bridge the gap by making camouflage “technical” clothing.

The two entrepreneurs quickly hit a roadblock because the two major camo patterns of the day, Realtree and Mossy Oak, were only licensed for use on certain fabrics — none of which met mountaineering specifications. The two hunters knew they needed to either make a new camo pattern or license one from outside the mainstream and then convince hunters it was just as good, if not better, than the hyperrealistic patterns they were used to.

Hart and Hairston’s company was called Sitka, and it soon caught the attention of W.L. Gore, the parent company of a little brand called Gore-Tex. Gore partnered with the brand and put its expertise behind developing a science-backed camo pattern to match Sitka’s high-tech designs.

Rather than mimicking the environment, Gore used a pattern that would confuse how an animal sees movement and outline, a principle similar to the military’s digital camo patterns.

The result was Sitka’s Optifade pattern.

Suddenly, manufacturers and hunters needed science behind their patterns too, and Sitka became the aspirational hunting brand that other companies followed.

Hairston broke off and founded another monolith of modern hunting gear, KUIU, and other brands like First Lite have since popped up.

By the mid-2010s, hunters were hungry for more advanced clothing, and companies began to develop it. They pushed new patterns, claiming each one was better than their competitors.

Hunters swore allegiance to specific patterns. Some became obsessed with every single piece of gear, from gloves to hats to socks, all in the same pattern and brand. TV personalities got wrapped up in sponsorship deals.

Everyday people amassed vast amounts of credit card debt as all kinds of products were sold wrapped in the hottest camo patterns, costing 40% more than the regular version. It was a whirlwind of camo, Velcro, and polyester. One company even introduced a mostly black “camo” pattern for sitting inside a dark ground blind.

RELATED – Tactical Flashlight: What to Look For Before You Drop the Cash

2020 to Today — Pattern Exhaustion and a Bit of Nostalgia

Today, it feels like we’re taking a bit of a breather. Most hunters have realized that the problem with being loyal to one pattern is that you might like a sweatshirt from one company and a pair of pants from another. Before you know it, you’re clashing — and all that science goes out the window. Long ago, many real work-a-day hunters realized matching every piece of gear was futile and absurdly expensive, and they started wearing mismatching patterns as a point of pride.

Some modern hunters are also questioning the efficacy of camo patterns altogether, instead opting for solid colors or simple “old-school” patterns. After all, people killed animals with sharp sticks for thousands of years without state-of-the-art patterned clothing.

Depending on the type of hunting you’re doing, putting a solid blaze orange vest over an expensive camo jacket seems like a futile gesture and a waste of money. You might as well wear your favorite Carhardt or something from Filson that will last a lifetime.

These days, hunting camo trends have mostly gone in three directions.

First, as mentioned, more hunters are turning to solid colors. Most hunting apparel companies now offer solid drab color options for their most technical clothing and gear. These pieces match up nicely with other brands’ clothes, and hunters aren’t at risk of a visit from the fashion police.

Second, some hunters are going with simpler throwback patterns. It started with young hunters digging through the crates of old-school patterns from Duck Hunter to Bottomland. Demand for these hunting camo patterns has trickled into the market with special-issue clothes and hydro-dipped guns.

Companies that still owned the rights to the old-school patterns many thought were dead started to give people what they wanted. Camouflage designer Mossy Oak released complete lines of gear in Bottomlands, and now you can get anything from pants to jackets and hats that look like your grandpa’s duck hunting gear from the ’60s. Only this gear is made of better stuff.

Some hunters even fill their freezers while wearing canvas pants and plaid jackets.

However, plenty of hunters are sticking with the technical patterns they love, and there’s nothing wrong with that. This could be because they’ve found an edge with a specific pattern, or they just think it looks cool. This has thinned the glut of patterns on the market — only the best and most popular have survived. (For the record, I think Optifade Open Country, KUIU Vias, and Browning’s Ovix pattern all look pretty rad.)

So what was happening to military camouflage during all this? Different branches swapped around patterns, but in the 2020s, all branches simplified things. Gone are the Army’s blueberry gear, the Marines’ host of pixelated designs, and the Air Force’s weird digital tiger stripe, which was actually the coolest of them all.

The entire military — except the Navy (mostly) — has transitioned to Multi-Cam, a relatively simple camo pattern heavy on browns and tan, but also includes a light black and shades of green in sort of blob patterns. It’s not as simple as the old Woodland and tricolor desert camo or the classic chocolate chip desert camo from the ’90s, but it’s close. It also seems to work in a wide range of environments.

Like hunters, the military has taken the long road to get back to where its camo started.

In recent years, hunters have also rediscovered the ghillie suit and animal parts as camo — and we’re not just talking about trad bow freaks who hunt covered in bear grease while wearing a loincloth.

With bowhunting video series from channels like Whitetail Adrenaline and The Hunting Public, we see bowhunters on the ground taking deer at ridiculously close ranges dressed in ghillie suits. What worked for the Scottish gamekeepers hundreds of years ago is still just as deadly.

Hunters are also returning to prehistoric camouflage by using animal parts or representations of animals to conceal themselves. Turkey hunters use fans to waylay unsuspecting gobblers, and pronghorn hunters hide behind silhouettes of bucks to get closer to their prey. I guess what worked for great-great-great-great-great-grandpa works just as well today.

READ NEXT – Rifle Backpack Guide: Buy One That Doesn’t Suck

Comments