Brad Cape, John Slowensky, Zach Smith, and Phil Yeomans are four elk hunters from Missouri who planned a Wyoming elk hunt in 2021. They mapped out a route to public land using the onX Hunt app, a real-time GPS tracker that shows property lines that would require corner crossing, the act of stepping over a property corner from one parcel of public land to another. Their destination was Elk Mountain, a picturesque peak at the northern end of the Medicine Bow Mountains in Carbon County, Wyoming.

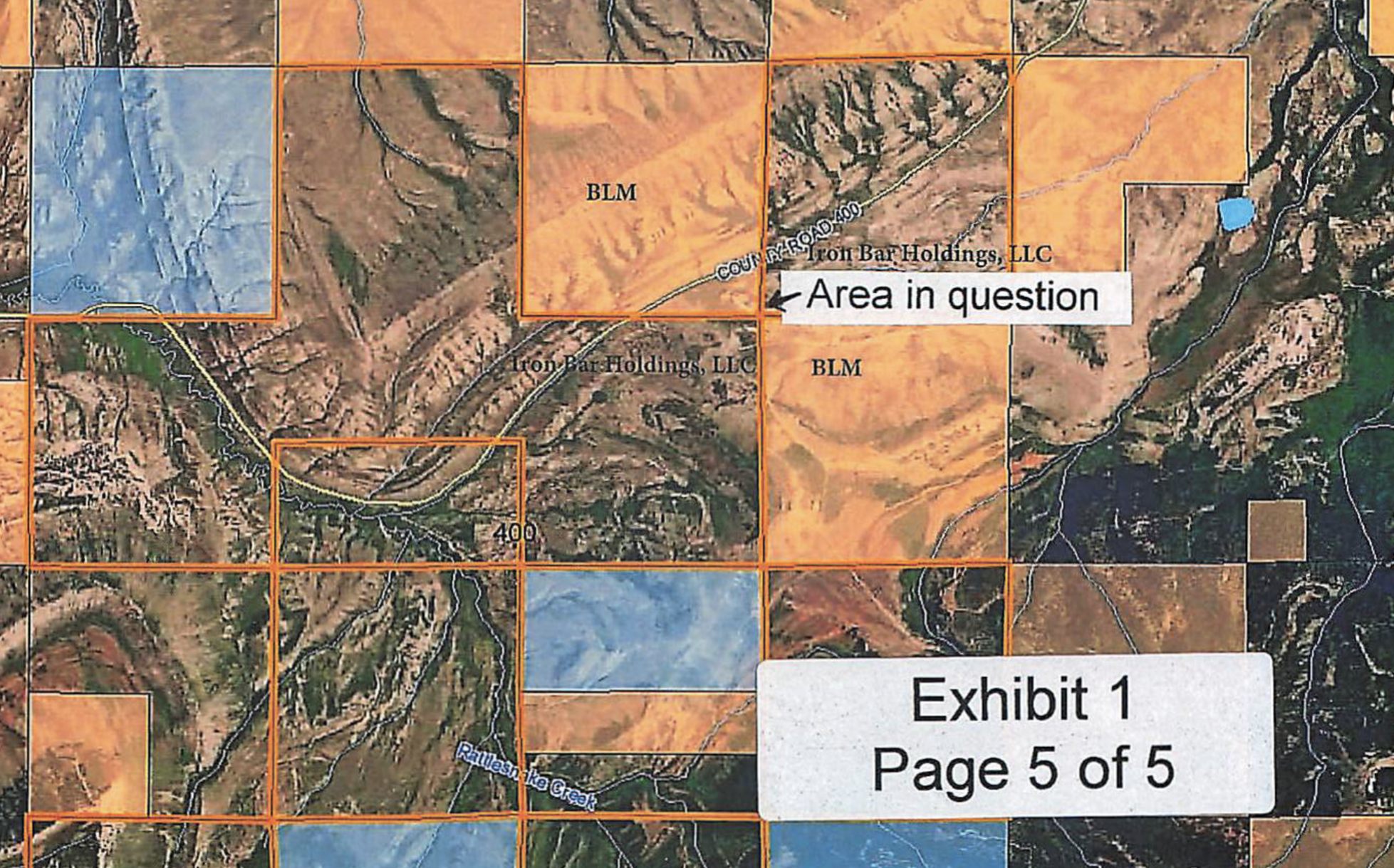

In Wyoming and many other western states, public and private land parcels mix in a grid pattern. The checkerboard property motif was a leftover from the United States’ westward expansion when the government granted railroad companies square-mile plots as they wound their way across the country. Boundaries rarely follow physical geography and have left large tracts of publicly owned property landlocked, meaning they are surrounded by private land.

With the help of onX Hunt’s topographic maps, the Missouri hunters were able to locate the exact spot where two squares of public land met corner-to-corner. They planned to step hopscotch-style between the two parcels of public land without planting a boot on the neighboring private property.

The other two points of the corner were squares of land owned by North Carolina businessman Fred Eshelman. Most of the land surrounding those public parcels are private pieces consolidated into the 22,000-acre Elk Mountain Ranch owned by Eschelman, the founder of a healthcare investment company and founding chairman of Furiex Pharmaceuticals. According to Forbes, Eshelman’s net worth exceeds $380 million.

Eshelman cannot legally run a fence along public-private checkerboard corners, so he posted two “no trespassing” signs, leaving only inches between them for the hunters to squeeze through.

RELATED – Court Declares New Mexico River Access a Constitutional Right — Again

Corner Crossing Is Not Illegal

Although not a single state in the U.S. has laws against corner crossing, Cape and his buddies took extra measures on a return trip to the area. In what was probably a smartass move, the hunters used a homemade stepladder to hop the corner between the signs, ensuring they didn’t accidentally brush Eshelman’s property with their hunting gear.

In response to the hunters’ snarky maneuver, Eshelman’s ranch hands chased the hunters with trucks brazenly driven across public land. They also called law enforcement to slap criminal trespassing charges on the elk hunters. Officers from the local sheriff’s office and the Wyoming Fish & Game Department informed Eshelman’s ranch manager that they did not issue trespassing charges for corner crossing.

Days later, local officials were pressured into issuing trespassing charges. In April 2022, a Carbon County Circuit Court jury found all four hunters not guilty of misdemeanor charges of criminal trespass and trespassing to hunt. It took the jury two hours to decide the men weren’t guilty of “violating the airspace” above Eshelman’s land.

However, the legal bullying wasn’t over yet.

“As this changing West comes in — the billionaires buying up ranches, climate change drying up grasslands and ranch land — all of that together creates this very fraught scenario.”

— Aaron Weiss, Deputy Director of the Center for Western Priorities

After the criminal charges didn’t stick, Eshelman lobbed a civil suit against the elk hunters, claiming millions of dollars in damages. The main contentions are that stepping over the corners of private property violates the landowner’s airspace, and granting public access would devalue his property.

The case is reminiscent of backseat “I’m-not-touching-you” sibling arguments, although this one has a David vs. Goliath edge that’s missing from most minivan squabbles.

As part of the lawsuit filed in February with the U.S. District Court for Wyoming, Iron Bar Holdings LLC, the legal owner of the sprawling ranch, alleges damages to be between $3.1 and $7.75 million.

In 2017, the property, which includes 22,042 acres and $5.96 million in buildings, was valued at $31.31 million.

Land Tawney, president and CEO of Backcountry Hunters and Anglers, a nonprofit sportsmen’s organization committed to preserving the North American heritage of hunting and fishing, called the damages claimed in the suit “the most egregious thing I’ve seen.”

“By claiming such large damages, the ranch owner is continuing a pattern of bullying, this time in court,” Tawney said.

The Wyoming Chapter of BHA launched a GoFundMe to help the hunters cover their rapidly accumulating legal bills. As of Dec. 7, the campaign has raised over $115,000.

“There are millions of acres of public land across the West that are not necessarily accessible to the public,” said Aaron Weiss, the deputy director of the Center for Western Priorities, a nonpartisan conservation and advocacy organization. “Hopefully, this lawsuit will eventually straighten out.”

The fight for access to publicly owned land isn’t limited to Wyoming. In Colorado, an 80-year-old fly fisherman and fellow anglers are fighting for access rights to the state’s waterways. In Utah, owners of former mining claims within the Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest have attempted to close public access to a popular skiing and hiking spot within the public lands.

According to the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership, over 16 million acres of public land are landlocked in 22 states. Because these parcels are wholly surrounded by private land, there is no permanent legal means for the general public, the people who own the land, to access them.

“As this changing West comes in — the billionaires buying up ranches, climate change drying up grasslands and ranch land — all of that together creates this very fraught scenario,” Weiss said. “All of it is coming to a head in this Wyoming case and in the Colorado stream access case. They’re all different facets of the same coin, I think.”

The corner crossing lawsuit is scheduled in U.S. District Court for Wyoming for June 26, 2023. The results could determine access to prime public hunting land across the country.

READ NEXT: Elk Hunting on Public Land: How To Build a 3-Year Strategy for a New Area

Comments